Regency Servants’ Hierarchy: During the Regency era, anyone with pretensions to gentility hired domestic help. There was no electricity or modern plumbing, so running a middle-class home involved a workload we can barely imagine these days. As for the town houses and country piles of the haut ton, an army of servants was needed to operate those grand status symbols.

Fortunately for the upper classes, servants were a dime a dozen and an early 19th century one-percenter typically earned 250-1000 times more than a footman. The gender gap in wages also provided the wealthy with more bang for their buck. Two maids, or three if they were really lowly, could be hired for the price of one footman. As a consequence, the presence of male servants was also a status symbol.

In The Complete Servant (1825), Samuel and Sarah Adams suggest a household income of £500 was needed before adding a footman/groom and £3000 before hiring a pair of footmen. For a family with an income of £3000, the Adamses propose a staff of 20 servants for a family, comprising: a housekeeper, cook, ladies maid, two housemaids, a laundry maid and a kitchen maid, a nurse and nurse-maid, a valet, a butler, two footmen, a coachman, two grooms, two gardeners and a laborer. The annual budget for this staff plus household equipages, horses, and liveries would amount to about £750 (roughly US$56,000 in today’s purchasing power).

Class and rank were of paramount importance in 19th century society as a whole, and servants could be as snobbish as their employers about upholding this rigid hierarchy. Every servant knew his or her place, and was expected to defer to those of higher rank.

The Regency Servants’ Hierarchy

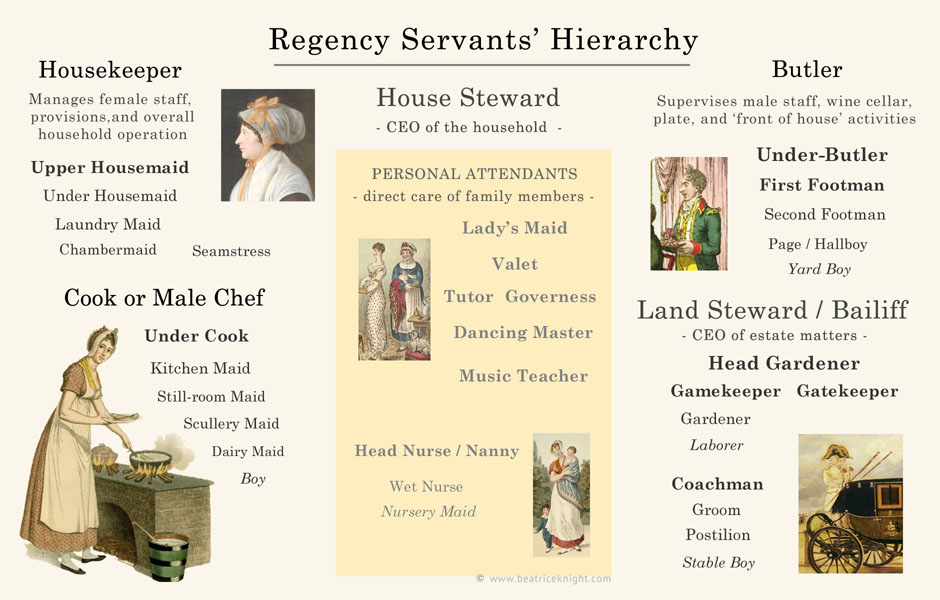

In a home with more than a few servants, the hierarchy was split into upper servants and under servants. The work of supervision fell to the upper servants, the most senior of whom – the housekeeper, butler, and steward (if there was one) – reported directly to the mistress or master of the household. Servants of lesser standing were directed along gender lines; men reported to the butler and women to the housekeeper. A hierarchy existed among the upper servants, all of whom operated with relative autonomy in their own spheres.

Steward: Men who owned grand homes and estates seldom had the time or inclination to supervise staff and operations in person, and hired a steward as their right hand, typically splitting the role between indoor and outdoor. A land steward, also known as a bailiff, would run the estate, collecting rents, arranging building and repairs, supervising farming operations, hunting activities and stables, and managing all the necessary staff. A house steward’s job fell somewhere between that of a personal assistant and staff manager. He was responsible for hiring, directing, and firing every domestic staff member. He managed the domestic accounts and oversaw the business of the house. Both the housekeeper and butler reported to him.

Housekeeper: A good housekeeper had to possess the knowledge, judgment and skills to implement her mistress’s wishes about the style and comfort of her home. If there was no house steward , the housekeeper added his accounting job to her tasks or split them with the butler. She ran the store room and still room, purchased all provisions, managed inventories, and supervised the staff. Many housekeepers also made home remedies, soap and cosmetics. She did not report to the butler but might diplomatically defer to him to uphold the example of gender roles. In general, the two worked in tandem and in many households, the housekeeper wielded more power than the butler in everyday staff management. If she did not think a footman was upholding the reputation of the household, he would be gone; the butler would probably break the bad news.

Butler: No upscale Regency household was without a butler. Head of the male servants, he was the visible face of the household, the captain of appearances whose dignified presence provided a reassuring symbol of his master’s status. He managed the wine cellars, acting as sommelier as needed, and was responsible for household security measures – locking up at night and vetting people coming and going. Under his auspices, service was smooth and elegant at the dining table, with the footmen kept on their toes. He deputized as the valet if his employer did not keep one – managing his master’s clothes and carrying out dressing room functions, morning and evening. If there was no house steward, he undertook household business matters seen as outside of the housekeeper’s domain.

Cook / Chef: the autonomous sovereign of the kitchen, the cook (or French male chef in some households) made all the food for the household, the servants’ meals, and entertainments. If there was no housekeeper, she also took on kitchen-related aspects of her role – buying provisions and dealing with kitchen accounts. All kitchen servants reported to the cook, and the cook reported directly to the mistress in some households and to the housekeeper in others. Tensions often existed between cook and housekeeper because of overlap in their responsibilities and relationship with their mistress.

The Ladies’ Maid. James Gillray, 1810

Valet / Ladies Maid: As personal family attendants, the ladies maid and valet had special status below stairs. The role was seen as a desirable step up for ambitious servants, offering perks like cast-off clothing and travel. The ladies maid dressed hair and managed her mistress’s wardrobe. She was often a companion, reading to her mistress, nursing her when she was indisposed and acting as her discreet confidante. The valet made sure his master was always well presented, acting as a barber, manicurist and dresser. These personal attendants had to be knowledgeable about fashion, etiquette and social mores, so their employers were always correctly presented for an occasion.

Governess / Tutor / Dancing Master: In an awkward category, the governess, tutor and dancing master did not exactly fit the class of “servants” but neither were they the social equals of their employers. They were usually educated people obliged to earn a living by polishing the social skills and accomplishments of other people’s children. They did not report to the butler or housekeeper and were seldom seen below stairs.

Lower Servants

The turnover of domestic staff in most Regency households was high. It was rare for lower servants to last more than a couple of years in a position before they moved on.

No servant symbolized the consequence of a household more than its footmen. From their height and good-looks, the turn of their manly calves, and elegance of their liveries, they made a statement and knew it. Satirical essays and cartoons depict lazy, insolent footmen with an inflated sense of their own importance. In real-life, footmen worked long hours and the sole footman in an establishment was usually overworked and exhausted. An ambitious footman could be promoted to under-butler, performing duties the butler handed over, such as cleaning the silver plate, brewing and bottling, and caring for the master’s clothing. Eventually he could work his way up to butler or valet.

Among the other lower servants were hall boys, footboys, running footmen, housemaids, nurses and nursery maids, laundry maids, maids-of-all work, kitchen maids, dairy maids, and scullery maids.

The Wet Nurse. Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837).

The Nursery: The fabled British nanny had not yet emerged in the Regency era. Her precursor was the Nurse, who occupied a position of great trust, as the woman responsible for the well-being of the heirs and spares. She reported directly to the mistress and ran her own kingdom in the nursery. Typically she had her own bedroom/sitting room adjoining the nursery and in a large family, she managed a fleet of nursemaids and wet nurses (who breast-fed infants). She might throw her weight around in the kitchen, ordering special foods for the children, mixing home remedies and treading on the cook’s and housekeeper’s toes. The education of small children fell in part to her before a tutor or governess took over, but at a time when child mortality was very high, the survival of her charges was her primary concern.

The Estate: Serving outdoors under the direction of the land steward or bailiff, or the master himself, were teams of staff from the estate and stables: the head coachmen and under coachmen, grooms, postillions, outriders/couriers, and stable boys; the head gardener, park keepers, gamekeepers, under-gardeners, and yard boys. The mistress of the house might play a role in the outdoors if she had an interest in gardening or landscaping. The planning of kitchen gardens and greenhouses could be at her behest, but typically the outdoors was “men’s work.”

Sources / Read More

Adams, Samuel and Sarah. The Complete Servant. London. Knight and Lacey, 1825.

Repton, Humphry. Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening. London. J Taylor, The Architectural Library, 1805.