When the Prince Regent was finally crowned King George IV, court dresses were wildly unflattering and expensive. He wasted no time dumping the archaic hoops mandated by his mother, Queen Charlotte for court appearances.

Regency Court Dresses

The palace of Holyroodhouse in Scotland made news with the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. The ancient seat of the Scottish kings, it was also a media focus during the Regency era, when the newly crowned King George IV decided to visit and hold a court there for his birthday in 1822, a royal ‘condescension’ that had not occurred in living memory. London newspapers of the day reported in consternation that although Holyrood House was the only Scottish castle not in ruins, it was doubtful that the king and courtiers could be accommodated in the manner to which they were accustomed. Rapid improvements were made, and Edinburgh smartened up the facades the monarch would pass as his carriage drove through the cobblestoned streets.

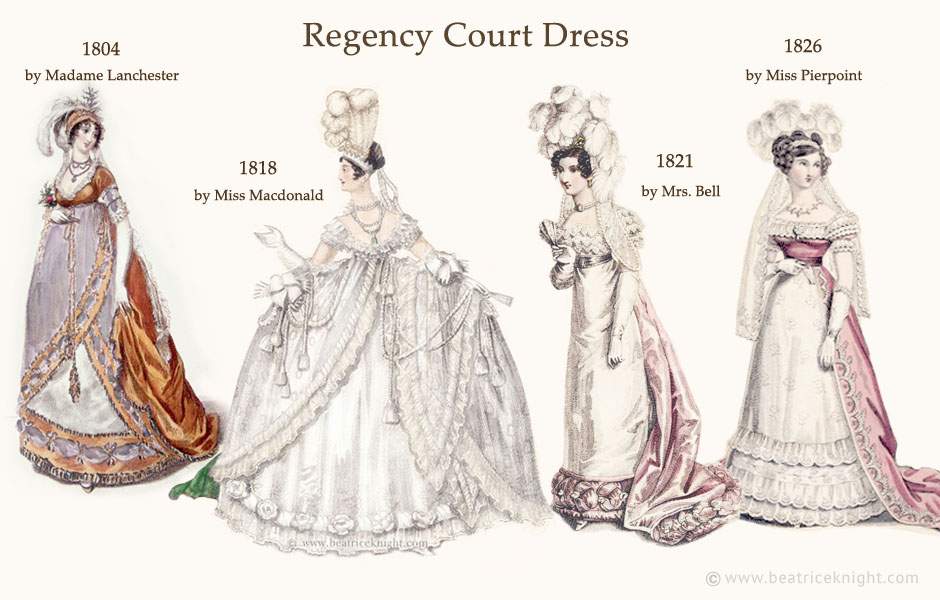

While the Scots (literally) painted the town, back in London, ladies of rank who intended to travel north for the court, descended on their modistes to order new dresses for the occasion. The Scottish colors of blue and white were a prevailing choice; an example appeared in the Ackermann’s Repository plate (left). But far more importantly, court dresses at last reflected the fashions of the day.

While the Scots (literally) painted the town, back in London, ladies of rank who intended to travel north for the court, descended on their modistes to order new dresses for the occasion. The Scottish colors of blue and white were a prevailing choice; an example appeared in the Ackermann’s Repository plate (left). But far more importantly, court dresses at last reflected the fashions of the day.

Upon taking the throne, King George IV had banished the archaic, unflattering hooped mantua court dresses his mother had insisted upon. It’s unlikely that anyone mourned the change. The new court dresses were far more flattering and could be adapted for evening or opera wear, once they had been seen at court. Despite the updated look, there were still strict instructions for court appearances. Nine ostrich feathers were the minimum required for the Holyroodhouse headwear in 1822 and women were warned of the hazards of moving backwards while managing a long train without assistance, a problem they never had in the good old days of hoops.

Memorable moments in Regency court dress

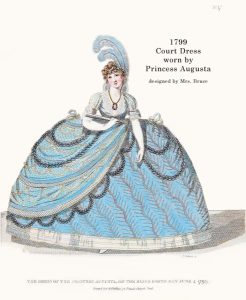

Some Georgian customs had evolved during the reign of King George III; court dress was not among them. It was the queen who determined protocol for her court, including attire worn to so-called Drawing Rooms. Not a woman at the cutting edge of new trends, Queen Charlotte stuck with the “mantua” look in vogue in the late 17th century, designed to show off ornately decorated skirts spread over hoops, accompanied by trains, feathered plumes, lappets, and fans.

R. Phillips. The Fashions of London and Paris, July 1799. Restored and recolored by Beatrice Knight.

With plenty of daughters at her disposal, she also indulged a predilection for mother-and-daughter fashion, frequently appearing in court with one of the princesses dressed in an outfit nearly identical to her own, as seen in 1799 when she and Princess Augusta wore the same silver spangled blue “crape” (below) for King’s Birthday on 4 June.

As the new century dawned, English women “modernized” court dresses by shortening the waist in a nod to the Empire look worn everywhere else. The result was a bizarre truncated silhouette that made the wearer look like a decorative teapot. This unflattering look defined court dress for the next two decades.

Leading Regency modiste, Madame Lanchester took a stab at a more graceful sensibility in a design (below) published in her upscale magazine Le Miroir de la Mode (1804), but no one was going to adopt such a French look while war with Napoleon constantly threatened security. The court dress of the day was epitomized in the 1805 design published by Tabart & Co (below, right), which ignored the natural waist and maintained the mantua tradition.

Big dress, big bling

Big dress, big bling

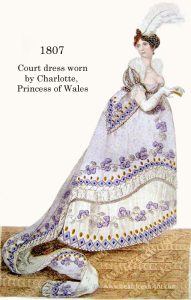

Although Regency court dresses from 1800 to 1820 were far too unfashionable to be recycled for the opera or a ball, a court appearance was no time for squeamishness about economies. Families whose finances were in the proverbial toilet, would sell paintings and borrow money to appear in court finery, and those who had already sold the family jewels wore paste substitutes. Diamonds and pearls were the designated gems; the more the merrier. At the Queen’s Birthday “Drawing Room” in 1807, along with the usual diamond bandeaus holding their plumes in place, women went all out. The Duchess of York, in white crape and blue velvet, spangled in gold, sported a ‘panache’ of seven ostrich feathers with a heron plume at the center, diamond headband, necklace and earrings, along with “a profusion of diamonds on the body, sleeve and girdle” of her gown. Not to be eclipsed, Countess Temple “wore three yards of diamonds valued at 90,000l on her dress, besides those on her head and neck.” That’s about $6.75 million in today’s dollars.

La Belle Assemblée, July 1, 1807. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight.

While the princesses usually wore colors to court, it was customary for young unmarried or newly married women to choose white or pastels. Senior nobility, however, appeared in rich, fashionable shades. The Countess of Ely had a statement to make at the 1807 birthday court, as her husband had just come to his new title and was being presented as the marquis for the first time. She chose a “petticoat of rich leopard satin tastefully ornamented with superb black lace and real sable; train of leopard satin trimmed with sable and lace to correspond,” a gown described by the Courier (20 January) as ” one of the richest and most expensive at Court.” Brown satin and velvet were popular that year, worn in mother-daughter style by the queen and Princess Augusta, and also chosen by the Countess of Cardigan and the Viscountess Borringdon.

Charlotte, Princess of Wales earned praise for a lavish dress featured in a fashion plate (left). Heavily fringed in silver and embroidered with emeralds, topazes, and amethysts in a grapevine pattern, it would have cost roughly the price of a nice house for a middle-class family.

Cumbersome court dresses were not without their advantages. Satirists of the day speculated that with so much standing about at court and a dearth of retiring rooms, a woman could find a dim corner and slip a bourdaloue under her massive skirt, if nature called. Others jested that a lover could be smuggled into the palace beneath the skirt and help his lady pass the time more pleasantly.

George becomes Prince Regent – court dresses remain hideous

When the Prince of Wales was finally declared Prince Regent in 1811, his estranged wife Princess Caroline did not occupy the customary role of consort. Increasingly caught up in scandal and fed up with living on the fringes of society, she finally left England in 1814.

During her son’s regency, Queen Charlotte held Queen’s Birthday Drawing Rooms each year, while the prince held levees for gentlemen. Except for flagging a few personal taste preferences (he liked extra plumes), the Prince Regent left court dress unchanged.

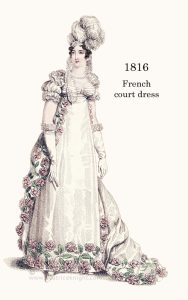

La Belle Assemblée, 1816. Retinted by Beatrice Knight

With the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, monarchy was restored in France and English elegantes could once again cross the channel to buy Paris fashions – and wistfully compare elegant Parisian court dresses like the one (right), in white satin, with the clunky unflattering equivalent. If anyone was brave enough to raise the topic of a silhouette change with Queen Charlotte, they did not brag about it afterward.

In 1817, London modiste Mrs. Bell, whose father-in-law conveniently owned La Belle Assemblée magazine, “invented” a new hoop that would at least make life easier for women stuck with wearing the designated mantua gown. I could not find an illustration of the hoop. From advertisements, it seems that Mrs. Bell created a more flexible, semi-collapsible version of the rigid hoop women had been wearing for the past seventy years. The description in La Belle Assemblée explained the new hoop: “…enables a lady to sit comfortably in a sedan, or other carriage, while the hoop is worn, with the same ease as any other garment…“

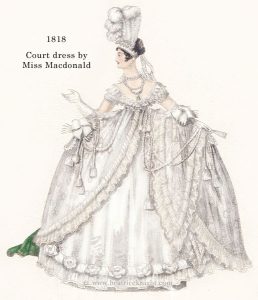

British Lady’s Magazine, 1818. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight.

This development did nothing to alter the court dress silhouette, as seen (left) in a design for the 1818 Season by one of London’s up-and-coming modistes, Miss Macdonald. In white satin with a green train, and tastefully embellished with blond lace and pearls, the dress typified the look favored for unmarried and newly married women making their debut at court. Commissioned by a young lady of high rank for her presentation, the gown must have boosted Miss Macdonald’s coffers, for she launched an expansion of her business and a marketing campaign shortly after.

1818 would mark Queen Charlotte’s last public appearance in April; she died on 17 November that year, and the court mourning period continued until 1819.

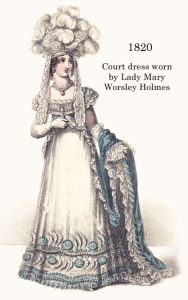

La Belle Assemblée. August, 1820. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight

The End of Hoops

When his father, King George III died on 29 January, 1820, the Prince Regent became King George IV and promptly imposed his personal stamp on court fashions. Big hoops were dumped overnight, and a few months later at the new king’s first Drawing Room, Lady Worsley Holmes wore the gown (right). From then on, court dresses would reflect the fashionable silhouette of the day.

With the new King George’s ascension, the Princess of Wales (living abroad since 1814) became Queen Caroline. The British government offered her a huge bribe of £50,000 to remain abroad, scandalizing Continentals, however she returned and settled in Hammersmith. She would never be given a role in the court, and never held a Drawing Room.

George IV’s Coronation was held on 29th April, 1821. Caroline had no place in the ceremony, but arrived at Westminster Abbey on the day, demanding admission, shouting at pages: “I am the Queen of England.” The door was slammed in her face. Nineteen days later, she died.

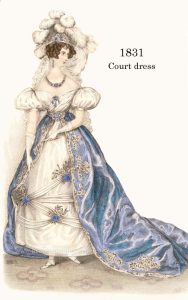

King George IV reigned in a decade of dramatic transition in fashion, coinciding with the peak of the Romantic movement from 1825-1835, the end of the Empire waistline, and the emergence of the gigot sleeve. Even though the king held very few Drawing Rooms, cancelling most because of illness, women had the chance to display their new court dresses in 1824, 1828, and 1829.

Royal Lady’s Magazine, 1831. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight

After his death in 1830, the throne passed to King William IV, whose wife Queen Adelaide presided over regular Drawing Rooms, where court dress reflected the fashion trends of the day. The king’s niece, Princess Victoria of Kent (destined to become queen on his death), attended court occasionally, but her mother kept her under virtual house arrest and thwarted attempts by William and Adelaide to draw her closer.

When she finally became queen in 1837, Victoria continued and expanded the protocols of Queen Adelaide’s court, including fashionable court dress. It was under Queen Victoria that the presentation of debutantes took center stage as never before, creating a huge demand for court dresses that continued for a century, until just before World War II.

Related Posts

Presentation at Court

Marriages between the upper echelon families of England were transacted much as mergers and acquisitions are in today's business environment. Each Season, the latest crop of prospects were introduced to the marriage market, [...]

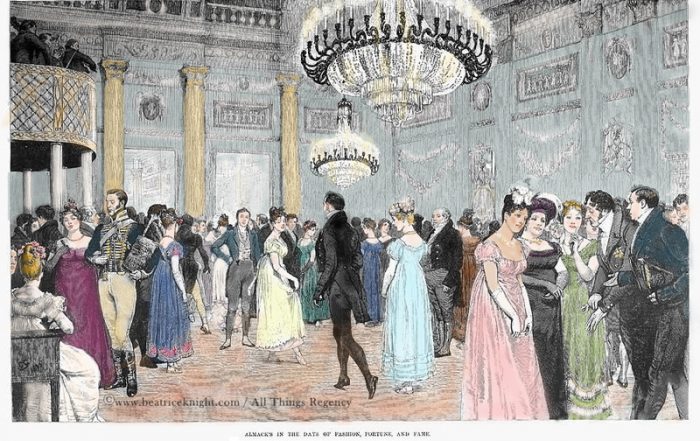

Almack’s History

As Ton Central for Regency high society, Almack's was all about exclusivity. That meant keeping out “mushrooms” (rich social climbers) and other undesirables. Almack's - a History To keep things classy, [...]