For the Regency dandy, taking snuff was a stylish ritual of such gravity that numerous books were published on the topic and tutors of snuff etiquette could barely keep up with demand.

The Right Snuff

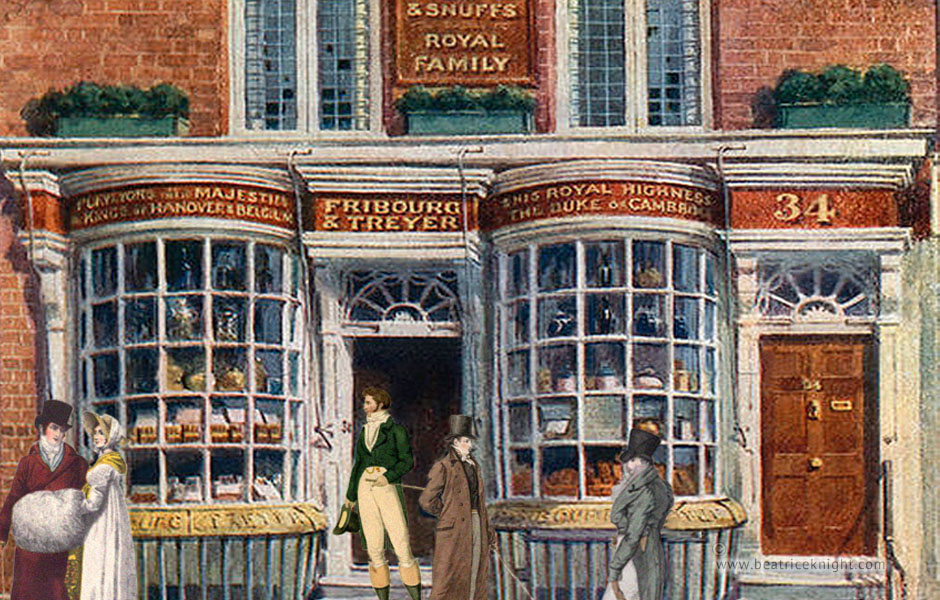

When George Brummell climbed the worn stone steps of Fribourg & Treyer, one afternoon, and entered the dim, aromatic interior, he was displeased to learn that the staff had forgotten to reserve his sample of a rare new snuff. “Very well,” he said, “then I shall condemn it.” Naturally, they handed over some other gentleman’s stash. Beau Brummell, the ultimate arbiter in all matters of fashion, was not above throwing his weight around. If he publicly disdained a new snuff blend, it was dead on arrival.

In Regency England, snuff was as synonymous with the beau monde as handsomely-tied neckcloths and white muslin dresses. More than a faddish recreational tobacco product, it was a social litmus. Nothing displayed good-breeding more than the quality of a gentleman’s snuff, the luxury of his snuffboxes, and the elegant reverence with which he performed the convoluted ritual of snuff-taking. Beau Brummell was seen to open his snuffbox and extract a pinch one-handed without spilling a grain.

Fribourg & Treyer was Snuff Central for the ton. Founded in 1720, a few steps from Piccadilly Circus at 34 Haymarket, the company was the most notable importer and manufacturer of high end snuff throughout the Georgian era. Beyond its brassed double bow-fronted window, regulars like Brummell, the Duke of Wellington, Viscount Petersham, and Lord Nelson stood at the hefty oak counter, sampling special blends, known as ‘sorts’ A huge leather volume recorded their customized blends. The best known of these, the ‘Prince’s Mixture,’ was the Prince Regent’s custom blend, made of dark Rappee tobacco scented with attar of roses. It is still sold today under the Fribourg & Treyer’s label as ‘Princes Special.’

How Snuff Was Made

To see his snuff made, a gentleman could go downstairs to the barrel-roofed workrooms where sacks of tobacco were stacked along tunnels that once connected a Roman baths. He would see a few craftsmen in long aprons operating a machine of spiked rollers which mixed cured tobacco leaves from several different varieties to form the basis of a ‘sort.’ The leaves were then ground into a powder, either coarse or fine, depending on the mix. During this process, their pungent natural ammonia was released, flooding the space with a distinctive sweet chemical aroma that was still present in its timber when the shop finally closed its doors in 1981.

Using secret methods handed down through generations, the snuff was blended with floral oils and spices to create the desired mix. After a maturing period of about two weeks, the snuff was sieved through mesh filters, the last of which was as fine as a silk stocking. The result was a powder fine enough to be inhaled through the nose.

When a snuff box was opened, you might expect a whiff of rose, violet, carnation, aniseed, mint, orange, or cinnamon, just to name a few. The most costly mixes called for up to a hundred essences.

Snuff Etiquette

It’s a movie cliché to see someone inhale a loud snort of snuff and erupt in a sneeze. Snuff theatricals of this ilk were and still are considered vulgar. During the 18th Century snuff-taking evolved into a ritual so convoluted, handbooks and pamphlets on the topic were bestsellers. The truly committed could even hire snuff etiquette tutors.

Any gentleman worthy of address was expected to offer his snuff in company. He would be judged on its quality and presentation–usually in a valuable ornamental box–and on the elegance with which he executed the rituals around its exchange. It is said that the Prince Regent’s infamous falling out with George Brummell may have been caused by a deliberate breach of snuff etiquette–serious stuff for the Regency dandy. To keep it classy, gentlemen followed these guidelines:

The Rules of Snuff-Taking

- With a few exceptions, gentlemen do not take snuff in the presence of ladies.

- Ladies (obviously!) should abstain from all tobacco products unless they are, say, Queen Charlotte.

- Never take snuff direct from a paper.

- Keep your snuffbox in an inner left jacket pocket.

- Take the snuffbox from your pocket and transfer it to the left hand.

- Tap the snuffbox with the middle and forefinger to accumulate the snuff at one side – this also signals the company that snuff is about to be offered.

- Open the box and inspect the snuff to be sure of the quality and quantity (enough for the group). There is no shame in closing the box and discreetly returning it to your pocket if it falls short.

- Offer the open snuffbox, with a bow, to the company before taking a pinch, yourself. The box travels clockwise around those who desire it, and is only held in the left hand.

- Do not sequester the box – always pass it along promptly.

- Receive the snuffbox back from the company in your left hand. Tap the side as before.

- Take a pinch of snuff between the thumb and finger of the right hand. Hold the snuff a moment, tilt the head back very slightly, and lift it to the nose – never hunch down over your hand.

- Inhale the pinch with both nostrils, keeping a pleasing countenance. Sniff, don’t snort.

- If you are a Continental, you may sneeze, cough, spit or gesticulate. But an English dandy would as soon be fed to wolves. Just saying.

- Close the snuff-box elegantly and return it to the appropriate pocket.

- Use a handkerchief to discreetly wipe your nose, collar, and neckcloth as needed.

Snuffboxes

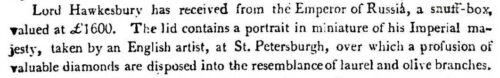

For the fashionable Regency blade, a snuffbox was indispensable, and also a status symbol accessory. The finest boxes were made of precious metals, porcelain or tortoiseshell, and often studded with diamonds and other gems, or miniature paintings by prominent artists such as the Venetian, Rosalba Carriera.

Collecting snuffboxes was quite the rage, and they were popular gifts, especially among royalty and aristocrats. In 1801, the Monthly Mirror reported (1 Nov. – below) that the Emperor of Russia gave Lord Hawkesbury an ornate snuffbox worth £1600 (about US $120,000 in today’s money).

Snuffbox by Rene-Antoine Bailleul 1779. Collections of the de Young and Legion of Honor museums of San Francisco, CA.

Viscount Petersham, one of the leading dandies of the era, boasted 365 snuffboxes in his collection, one for each day of the year. He was obsessed with snuff, and when he died, he left an array worth £3,000 – nearly quarter of a million dollars in 2023 spending power. His snuffboxes remained in the family for many years, and were eventually sold in the mid-20th century to various private collectors and museums.

Lord Byron was another avid collector, spending some 500 guineas on several boxes at a time. Eventually, he sold most of his collection to pay for his expensive and disastrous campaign in Greece.

In recent times an important collection of porcelain snuffboxes set a world record of £1,700,000 at auction. The collection comprised some 80 items reflecting the history of European snuffboxes.

Assassination by Snuff

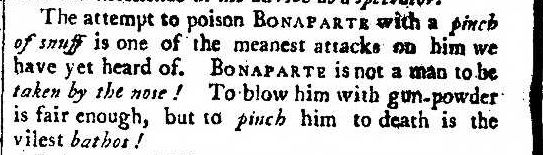

Courier and Evening Gazette. Aug. 14, 1801

In August, 1801 British newspapers reported with a combination of mockery and disgust on an attempt to assassinate Napoleon Bonaparte with poisoned snuff. Among more than 20 attempts on his life, two at least revolved around snuff. The French emperor was a famed connoisseur, who often gave and received snuffboxes as gifts.

The first attempt was foiled when servants became suspicious of a snuffbox on the then First Consul’s desk at his newly renovated apartments in Malmaison. In his memoirs, Napoleon’s valet, Constant later wrote that certain stone-cutters among the renovation crew were in league with the conspirators.

Snuffbox miniature of Napoleon Bonaparte, Jean-Baptiste Isabey, about 1812, possibly France. © The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1803, a more thorough plan was hatched in London, aimed at restoring the Bourbon monarchy. Known as the Pichegru Conspiracy or the Cadoudal Affair, its architects were Georges Cadoudal, a Breton Chouan leader financed by the British government, and Jean Pichegru, a general of the Revolutionary Wars, who lived in exile. Pichegru attempted to enlist General Jean Moreau in the plan, but Moreau was never in favor of restoring the monarchy.

In August 1803, Cadoudal and other conspirators left London and travelled to Paris. Not long after, the French arrested a British spy who revealed details of Cadoudal’s plan. Napoleon arrested and executed the chief conspirators.

Snuff has a long history of popularity among female movers and shakers. St. Teresa of Ávila had a fondness for Spanish snuff and was known to have received snuffboxes as gifts. Marie Thérèse de Lamourous wrote of kissing and trying on St. Teresa’s mantle at the Carmelite convent in Paris: “I remarked everything, even the little stains, which seemed to be of Spanish snuff.”

Catherine de Medici found snuff so helpful as a headache remedy, she named it Herba Regina (Queen Herb). Following her lead, French nobles adopted snuff and eventually Marie Antoinette became a fan.

Like Catherine de Medici, Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, found snuff indispensable as a headache remedy. She was so partial to it, she was nicknamed ‘Snuffy Charlotte’ She preferred highly scented blends, such as her favorite, Violet Strasbourg, a mixture of powdered rappee, bitter almonds, ambergris and attarju, which she combined with a spoonful of green tea each morning.

The queen filled a room at Windsor Castle with her personal stash of 350 bottles, created by the Royal Manufactory of Seville. She also had a collection of almost 100 snuffboxes, many of which were auctioned off in Queen Charlotte’s Sale, May 1819. Among these was the box (below) made of amethystine quartz and set with a floral design of gold, rubies and diamonds. This was handed down through several generations of royals to Queen Mary, who had an interest in Queen Charlotte, and added it to a collection of her personal effects.

How Snuff Took Off in England

Although tobacco was introduced to Europe from the New World in the early 1600s, it was not popular in England until late that century. In 1660, when King Charles II returned to England to reclaim his throne, he and his court brought snuff-taking back from France with them. Until the early 1700s, snuff was popular almost exclusively among the nobility–no one else could afford it. The lower orders smoked tobacco, usually in pipes.

In 1702, everything changed. Under the command of Admiral Sir George Rooke, the British, having mounted a failed campaign against Cadiz, attacked the Spanish fleet in the Port of St. Mary and seized a rich booty of high-quality prepared snuff. A few days later they struck Vigo Bay, where several Spanish merchant ships had just arrived from Havana. When they returned home, they sold the so-called Vigo Prize snuff in various seaports at moderate prices, flooding the market with a large quantity of excellent snuff.

Up until then, English snuff-takers usually prepared their own tobacco powder from the same dried tobacco used by smokers. Tobacco leaves were twisted and dried in rope-like carottes for purchase by snuff-takers, who would use a snuff rasp, like a grater, to grind the day’s supply of snuff from the end of a carotte. Rasps were also a collectible accessory, and the best were made of precious metals, carved ivory, bone and fine woods.

With the availability of the Vigo prize, snuff’s popularity exploded. It was less hassle to use, and an increased customer base induced more English imports. Smoking was firmly relegated to the lower echelons and the coffee houses and taverns they frequented. The beau monde embraced snuff, and at most elegant assemblies smoking was banned outright, in a move led by Beau Nash, the Master of Ceremonies at Bath from 1705.

Despite its popularity, and a reputation for medicinal benefits, snuff was viewed by some as unhygienic and damaging for the nose and lungs. Its popularity began to wane in 1820, when the government relaxed its taxation on cigars, and gentlemen adopted cigar-smoking as their preference at London clubs. By the time Queen Victoria came to the throne, society’s elite had largely switched their tobacco consumption away from snuff, and it became associated with decrepit dandies, maiden aunts, and eccentric grandparents.

Sources and Resources

The Lethbridge Herald. May 2, 1961

Bourne, Ursula. Snuff. Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications, Ltd., 1990.

Fink, Thomas. The Man’s Book. London: Orion, 2006.

Libert, Lutz, Tobacco, Snuff Boxes and Pipes. London: Orbis, 1984

Pinto, Edward H., Wooden Bygones of Smoking and Snuff Taking. London: Hutchinson & Company, Publishers, 1961.

McCausland, Hugh, Snuff and Snuff-Boxes. London: The Batchworth Press, 1951.

Shepherd, C. W., Snuff: Yesterday and Today. London: G. Smith & Sons, 1963.

Related Posts

Presentation at Court

Marriages between the upper echelon families of England were transacted much as mergers and acquisitions are in today's business environment. Each Season, the latest crop of prospects were introduced to the marriage market, [...]

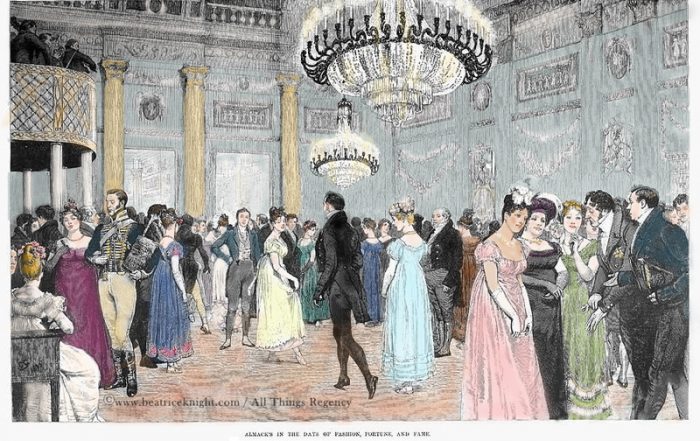

Almack’s History

As Ton Central for Regency high society, Almack's was all about exclusivity. That meant keeping out “mushrooms” (rich social climbers) and other undesirables. Almack's - a History To keep things classy, [...]