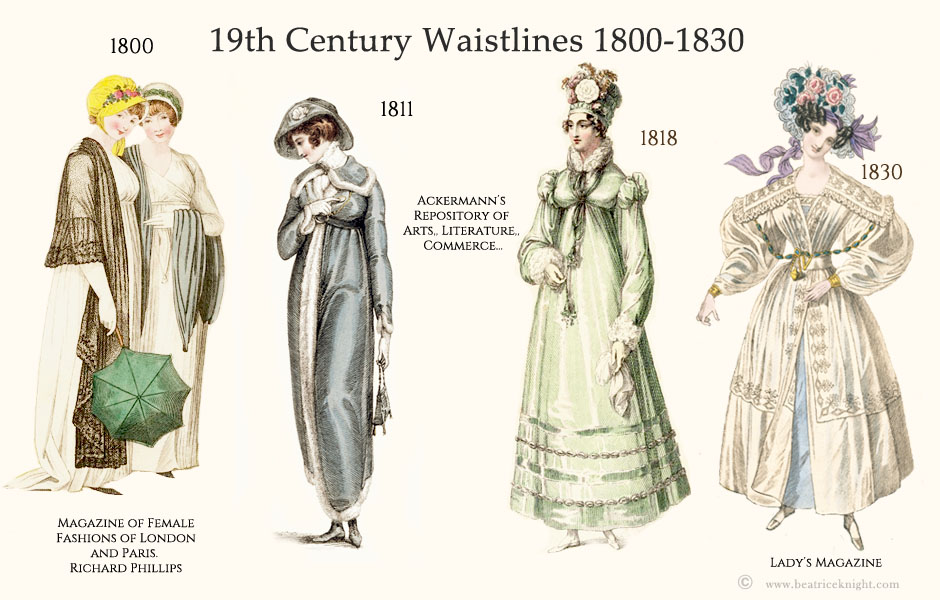

Empire waists and white muslin dresses are synonymous with the Regency era. The look defined early 19th century English fashion for over 20 years.

This post is the first of three about changing waistlines during the era. Part Two covers the formal Regency period from 1811-1820 and Part Three the decade from 1820-1830, when the Prince Regent reigned as King George IV.

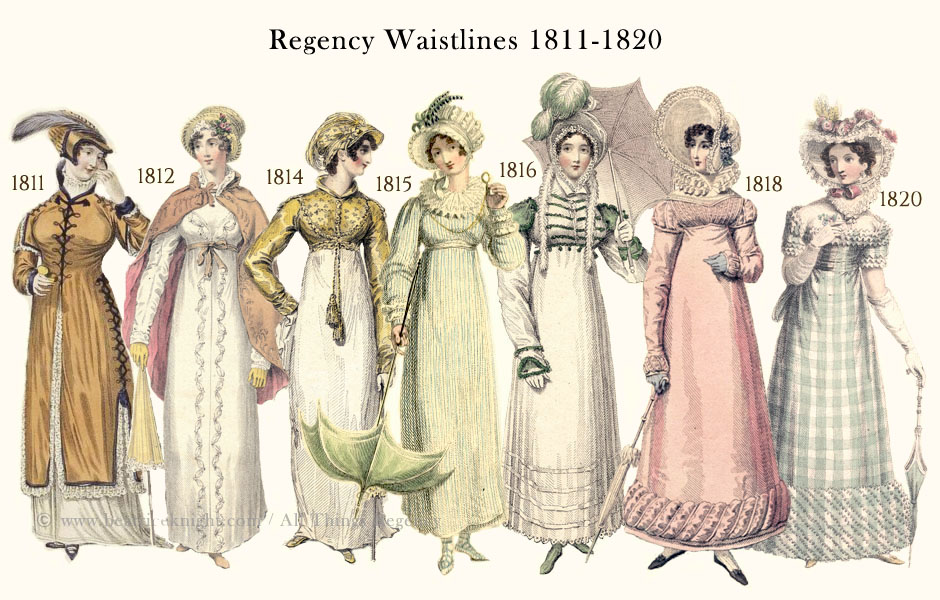

Regency Waistlines Part Two 1811-1820

When George became Prince Regent in 1811, Great Britain had been at war with Napoleon for seven years. Decoupled from Paris trends, English fashions had gone rogue. Regency Waistlines Part Two - [...]

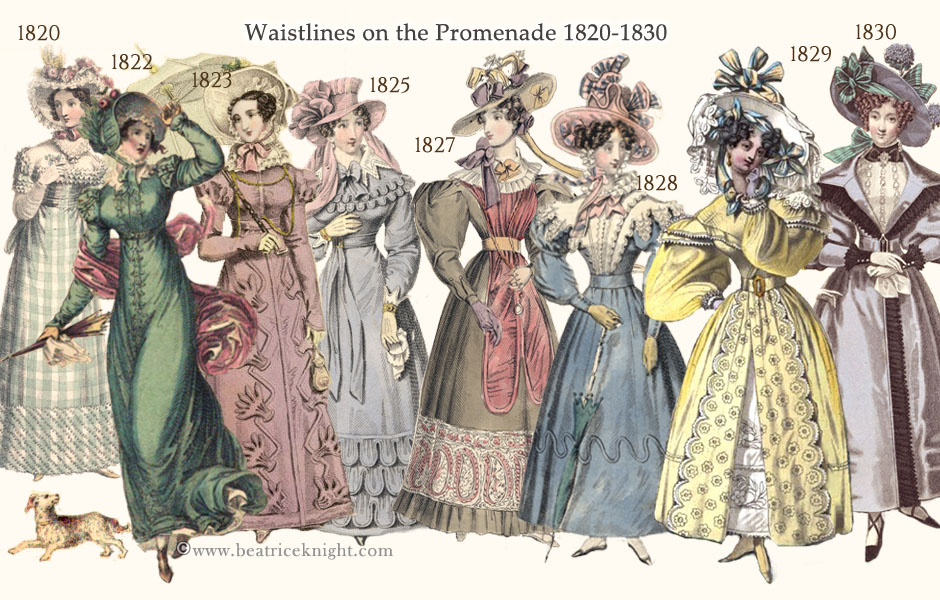

Regency Waistlines Part Three 1820-1830

Empire waists epitomized Regency England, but change was underway when the Prince Regent finally took the throne as King George IV in 1820. The broader Regency era would last until his death in 1830, [...]

Regency Waistlines Part One

As the 19th century dawned, English fashion was more or less in lockstep with Paris. Decades of so-called anglomanie in France had been sparked by Voltaire’s love affair with English culture in the 1720s. Coupled with the Francophile tastes of the English upper crust, a mutual admiration society had functioned alongside the traditional rivalry between the two nations even through the French Revolution. This screeched to a halt, at least publicly, when the two countries went to war in 1803. But the “little white dress” synonymous with Empire, as ordained by Napoleon’s dress code, would remain a fixture for some 20 years in Great Britain, especially for young unmarried women.

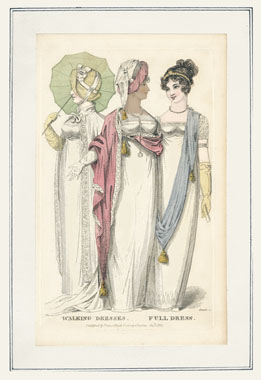

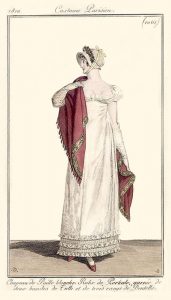

Ladies Museum, September 1807. Recolored by Beatrice Knight

As the war dragged on, embargoes, travel restrictions, and censorship made it next-to impossible to keep abreast of Paris trends, however ladies’ magazines still padded their pages with breathless updates supposedly gleaned from correspondents lurking about French parks to observe strolling élégantes. It was mostly “fake news.” Mail between the two countries was censored, and any English person caught in Paris was placed under house arrest or imprisoned for spying.

Decoupled from French influence, English fashion finally went rogue. The gaze turned inward, reflecting patriotic sentiment and the increasing influence of the Romantic movement. Fashion was often driven by fads: Tudor one year, Spanish another. Military touches were virtually mandated, especially after victories.

Before the formal Regency period (1811-1820), waistlines were ‘Empire’ but ranged from medium low to medium high from 1800 to 1807, and hems dragged so much that in a letter to La Belle Assemblée in July 1806, a writer decried demi-trains: “...in the streets, the theatres, or crowded rooms what are they but so many public dusters? … For pity’s sake, Ladies, no longer permit your dress to be a public calamity!”

Ladies magazines started depicting shorter hemlines for walking dresses that year, but it was 1808 before Englishwomen finally adopted “walking length” hems that brushed their footwear instead of sweeping the floor.

Classical silhouettes dominated Regency fashion from 1800 to 1807, with characteristic looks that can be summarized as follows:

1808 – 1809. Waistlines Dive

The miserably hot summer of 1808 saw women seeking relief from the pressure of stays that pushed up the bosom.

In July La Belle Assemblée told readers that since their previous issue “…the long waist is becoming universal.” That was something of an overstatement, but the waistlines shown (left) had started to lengthen soon after that fashion plate was published in the Ladies Museum (Sept. 1807) and continued to drop through 1808.

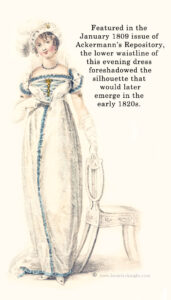

Ackermann’s Repository. January, 1809

By 1809, longer waists were a major trend for “full dress” in the evenings, when a woman was under pressure to dazzle the company with a gown from some pricey London modiste. The transition was a little slower in walking dresses, as women were reluctant to cast off styles from recent seasons.

In January 1809 Ackermann’s Repository described an evening dress (right) created by the famous Madame Lanchester, of white satin trimmed with blue velvet which featured “an antique stomacher ornamented with diamonds mounted in gold.” In this design, the waistline was well down the midriff, and the silhouette looked like a forerunner of early 1820s styles.

In January 1809 Ackermann’s Repository described an evening dress (right) created by the famous Madame Lanchester, of white satin trimmed with blue velvet which featured “an antique stomacher ornamented with diamonds mounted in gold.” In this design, the waistline was well down the midriff, and the silhouette looked like a forerunner of early 1820s styles.

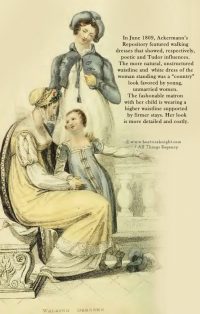

Young unmarried women, like the one in the family group (left-Ackermann’s, June 1809), continued to wear simple white or sprigged muslin. Married women of all ages, especially in town, sported more detailed, stylish modes.

The longer waist and “round bosom” style was flattering, romantic, and easy to wear. Women favored the more comfortable look and less rigid stays. Hems rose for walking dresses until by late 1809, some fashion plates showed ankles. But just as women began to get comfortable, the new emphasis on longer waists ushered in narrower bodices. Stays weren’t going anywhere.

In November 1810, the Princess Amelia died after a long illness, and the court ordered a period of general mourning. Women wore somber fashions for the next few months. In December, Ackermann’s featured a suitable carriage / walking outfit (right) and La Belle Assemblée chose an evening dress of black net over a white satin slip (left) and informed readers that the neckline of evening dresses should “sit perfectly square, and give as great a breadth to the bosom as possible…” A longer waist added emphasis to this silhouette.

In November 1810, the Princess Amelia died after a long illness, and the court ordered a period of general mourning. Women wore somber fashions for the next few months. In December, Ackermann’s featured a suitable carriage / walking outfit (right) and La Belle Assemblée chose an evening dress of black net over a white satin slip (left) and informed readers that the neckline of evening dresses should “sit perfectly square, and give as great a breadth to the bosom as possible…” A longer waist added emphasis to this silhouette.

Every magazine and newspaper ran blow-by-blow accounts of His Majesty’s health, which paved the way -finally – for Parliament to declare “Prinny” Regent in early February 1811. The Regency period had formally begun.

Meanwhile, in France, bosoms are jauntée...

Meanwhile, in France, bosoms are jauntée...

In post-revolution France, much as in post-revolution Iran some 175 years later, all men were granted equal rights. Women, on the other hand, were equally deprived of rights, which included the right to choose their clothes. French women, unlike their counterparts in Iran or Afghanistan today, were not beaten on the streets or sentenced to prison for dress code violations. However, Emperor Napoleon’s Civil Code of 1804 not only banished them from professions and erased their civil rights, the rules also imposed the Emperor’s taste in women’s wear. The Empire waist and Classical white were not just a trend; they were de rigueur.

As the years passed and France pillaged half of Europe, a few modifications crept in. Dresses became more structured, fabrics less flimsy, hems lifted, trim was more elaborate, and colors made their presence felt in wraps, pelisses, and over-dresses. In 1810, as in London ballrooms, the bosom was center stage in France, spilling over broad, square necklines. But waistlines would remain stubbornly Empire until Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo in 1815.

A little backstory: The influence of the Revolution on French fashion was already profound when Napoleon took over. While the guillotine was laboring non-stop in the streets of Paris, no one dared gad about in the lavish styles of the ancien régime. In the short space of three years, about half a million citizens were arrested, 17,000 were officially executed and many more murdered by the mob. Another 10,000 died in prison before trial. For self-preservation, Frenchwomen wore the garb of the revolution; some even dressed as men and flaunted their zeal with the bonnet rouge (red cap).

Incroyables et Merveilleuses

Immediately after the Terror ended, a counter-revolutionary fashion backlash was led by aristocrats who had lost loved ones to the guillotine. Known as Incroyables and Merveilleuses, they affected outlandish styles and mannerisms, and used in-your-face symbolism to rebuke those whose silence made them complicit in the slaughter of people they once counted as friends, neighbors, and even family. It was during this time that hemlines lifted and damped muslins clung to naked flesh – much to the delight of satirists.

Some 40,000 French émigrés had sought refuge in England during the chaos. Many set themselves up in the fashion industry as modistes and milliners, catering to the Francophile tastes of the English upper class.

A good number returned to France during the Directoire period (1795-1799), sparking a renewed period of anglomanie, in which the French fell in love with all things English. The shawl and the spencer became necessities. When Englishwomen crossed the channel, they found their modest country styles considered the height of fashion.

The two countries would never be so aligned in style again. As the 18th century ended, Napoleon’s star was rising and France would soon remake itself and impose control over much of Europe.

1811-1830

Changing waistlines over the next two decades are discussed in Part Two and Part Three of this series.

Sources

Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: a Comprehensive Guide. Dover, 1990.

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. New York. Garland, 1989.

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

The Mirror of the Graces. Crosby & Co. London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London