Reticule or Ridicule – the Regency woman’s cute hand purse

She was clearly a gentleman’s daughter. The spilled contents of her ridicule included a sandalwood fan, smelling salts, a folded prayer card, two gold guineas, and a handkerchief with the initials C.E.W. picked out unevenly in primrose silk. Alverstone by Beatrice Knight

“…When, however, neither kind words nor gestures could prevail on Mansell to accept the cakes, he thrust them into her ridicule and respectfully kissed her fair hands…” Ackermann’s Repository. January, 1815

She was clearly a gentleman’s daughter. The spilled contents of her ridicule included a sandalwood fan, smelling salts, a folded prayer card, two gold guineas, and a handkerchief with the initials C.E.W. picked out unevenly in primrose silk. Alverstone by Beatrice Knight

“…When, however, neither kind words nor gestures could prevail on Mansell to accept the cakes, he thrust them into her ridicule and respectfully kissed her fair hands…” Ackermann’s Repository. January, 1815

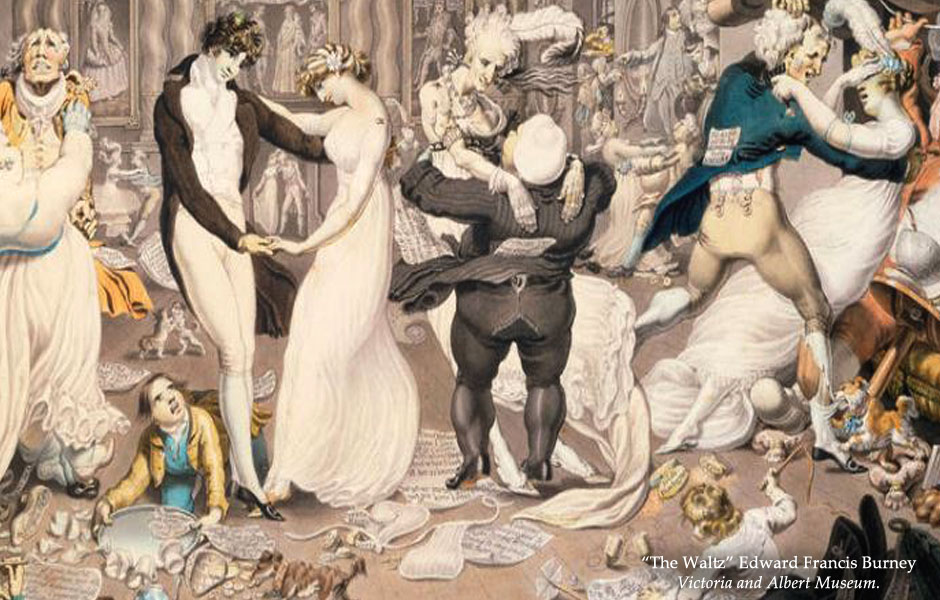

With the shift to flimsy muslin Empire line gowns in the late 18th Century, pockets became old hat, especially among elegant young ladies. They were lumpy and hidden, and sometimes still tied about the waist instead of being attached to clothing seams. The new fashions called for a more decorative accessory.

The reticule was an instant hit when it emerged onto the fashion scene in the late 1790s. The first ‘ridicules’ were

When the reticule first appeared, it was made of netting. As time went by, they were made from various fabrics, including velvet, silk, and satin.[4] A reticule usually had a drawstring closure at the top and was carried over the arm on a cord or chain. Reticules were made in a variety of styles and shapes and sometimes trimmed with embroidery or beading. Women often made their own reticules.[1][3][5]

A reticule, also known as a ridicule or indispensable, was a type of small handbag or purse, similar to a modern evening bag, used mainly from 1795 to 1820.[1] According to the American Heritage Dictionary, the name “reticule” came from the French réticule, which in turn came from the Latin reticulum, a diminutive of rete, or “net”.[2]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Yarwood, Doreen (2011) [1978]. Illustrated History of World Costume. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-486-43380-6.

- ^ reticule. (n.d.) American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. (2011). Retrieved May 19, 2016 from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/reticule

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kloester, Jennifer (2010) [2005]. Georgette Heyer’s Regency World. Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4022-4136-9.

- ^ reticule. (n.d.) Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary. (2010). Retrieved May 19, 2016 from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/reticule

- ^ “The History of Bags and Purses”. Tassen Museum Hendrikje Museum of Bags and Purses. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018.

The pocket was invented as a crime-stopper

Long before the Georgian era, both men and women used to carry coin and personal essentials in pouches at their waists. These visible pouches became a fashion accessory, many of them beautifully detailed. They were also a target for “cut-purses” – the bag-snatchers of the Tudor era. As “cut-and-run” became increasingly prevalent in the 1600s, people started to hide their purses inside their clothing, cutting slits in their garments for access. However, the customary pouch created a tell-tale bulge that could interest a thief, so the “pocket” was born.

Pair of embroidered pockets 1800-29. ©-Victoria-and-Albert-Museum-London

Since nobody was going to see them, pockets did not have to be ornamented, merely practical and easily accessible. They evolved as seamed cloth bags, usually in a pair, flat in shape, big enough to hold important items, and out of reach for all but the most determined thief. It’s no accident that the cut-purse job-title was soon replaced with “pick-pocket.” Most examples I’ve seen of pockets were about 10 inches deep and 7 inches wide, and the nicer ones were quilted and embroidered. Most often the pockets were secured about the wearer’s waist with ties and she could access them via pocket holes in her dress. Nancy Bradfield’s book, Costume in Detail, shows Regency gowns with slits in convenient places – under the arms and concealed at the sides.

Pockets were sold by haberdashers and warehouses, and were considered undergarments. Those worn by servants and working people were basic, functional bags made of sturdy cloth like fustian, which could be worn under an apron if not beneath a dress. Wealthier women wore more elegant cotton and linen bags, often quilted and shaped.

As far as crime goes, the pocket was a double-edged sword, providing thieves with a means to hide stolen goods on their person, as seen from various criminal cases in the records of the Old Bailey. At the Vitoria Fete of 1813, multiple arrests were made of pick-pockets who worked the massive crowds at Vauxhall Gardens that evening, filling their pockets with booty. Theft at the auctions of book collections was described in the Morning Chronicle ( July 2, 1813) as occurring “to an extent that made it necessary to place a watch to discover the depredator…. ” The report continued, that at viewings of a library auction by Leigh and Sotheby, “a young man was detected in putting a volume into his pocket…which did not belong to him. It was “The Oxford Sausage,” bound up with other tracts.” Upon searching his lodgings sixteen other volumes from the same auction were discovered. Apparently his pockets were capacious enough to hold hefty books.

Despite the adoption of pockets by the criminal element, their popularity grew, and they would become so indispensable that the in-seam pocket soon became integral in men’s clothing, appearing in vests and coats in the late 1800s. Women’s pockets were not made in-seam until almost the 19th century. There was a reason for that.

For women, reticules and pockets made a perfect, functional combination

For the Regency woman, the reticule meant having her cake and eating it, too. Pockets had become indispensable as covert storage for valuables and sentimental items like letters and miniatures of loved ones, as well as practical items. At night, pockets full of treasured personal items could be placed under one’s pillow, safe from inquisitive eyes and pilfering. There was no way women would replace their precious pockets with a small bag dangling from their wrist, especially not working women. Records of thefts from the era, show seamstresses, and vendors who operated stalls and dairies, along with thousands of women who did paid work, kept small tools, pencils, pins, spectacles, scissors and other necessities in their pockets. Thieves were sometimes identified because women could describe the items they kept in a stolen pocket.

Safe storage options were not readily available to working people in the Regency era, or even to women of the upper classes. Surrounded by servants, women of rank lived in fish bowls and often stored their most precious items in pockets, including personal seals, snuff boxes, pocket-books, watches, combs, and mementos. Still, no one wanted to be seen groping about beneath her gown for smelling salts and what not. The reticule solved that problem. Re-inventing the pouch of yesteryear, it provided women with instant access to functional items like hand-fans, ready money, handkerchiefs, smelling salts, and visiting cards.

Embroidered silk reticule ca. 1815. Victoria and Albert Museum.

A couple -Incroyables. 1795,. Adapted by Beatrice Knight from an unknown German fashion plate.

Some fashion historians suggest it was first popularized by Queen Marie Antoinette. The trend caught on rapidly and just like the handbags of today, beautiful reticules became a must-have fashion accessory and a status symbol.

Reticules appeared in fashion plates from about 1795 onward. One of the earliest examples I could find depicts a French couple of “Incroyables”. The woman is carrying a substantial drawstring reticule, possibly made of kid leather. As the Regency era progressed, women matched reticules to their outfits. Many have survived, including examples made of metallic mesh, tortoiseshell, leather, and fine textiles.

The Pineapple Reticule

Photo via Focus Features

The pineapple reticule, a style from the early 1800s based on the prestigious fruit, reclaimed its fame recently in the beautifully costumed movie Emma (2020). Costume enthusiasts had been creating these for many years, such as the example (left), but movie sparked renewed interest in the quirky Regency accessory, and there are patterns all over the Internet for anyone wanting to sew or knit the cutest reticule ever. Keep in mind, no one knitted a reticule during the Regency, so if you want authenticity, stitch your by hand.

The reticule outlived detached pockets, surviving until the 1920s, then evolving into coin purses and wallets.

Pineapple reticule knitted by KnittyVet

Well before then, pockets in women’s clothing had finally been integrated and the in-seam version was shallow, flimsy, and insecure. The large, practical pockets of our foremothers emerged from beneath skirts and bodices to become messenger bags, totes, mini-bags fanny packs, money belts, and of course purses and handbags. Thieves have not stopped stealing them. But women in the fortunate countries of the world now have more options for safekeeping cash and important personal items. Purses are not essential, anymore, but they are a status symbol accessory, just as reticules once were, and no one is putting their cell phone and make-up in the in-seam pockets found in most women’s clothing.

Read More

Bradfield, Nancy. (1997) Costume in Detail: Women’s Dress 1730-1930. New York. Costume & Fashion Press