A simplistic inflation calculation does not give meaning to Regency spending power. Lord Byron could have hired ten scullery maids for the price of a musical snuffbox he purchased in 1813 – £105.

According to Samuel and Sarah Adams (The Complete Servant, 1825), an income of £100 a year would enable a Regency household to hire a maid-of-all-work, for about £5-10 per year. This poor dogsbody might hope to save the price of Lord Byron’s snuffbox in the course of her lifetime. She would have found it unthinkable to spend an entire month of her wages on a volume of his poetry – 12 shillings in 1813.

According to Samuel and Sarah Adams (The Complete Servant, 1825), an income of £100 a year would enable a Regency household to hire a maid-of-all-work, for about £5-10 per year. This poor dogsbody might hope to save the price of Lord Byron’s snuffbox in the course of her lifetime. She would have found it unthinkable to spend an entire month of her wages on a volume of his poetry – 12 shillings in 1813.

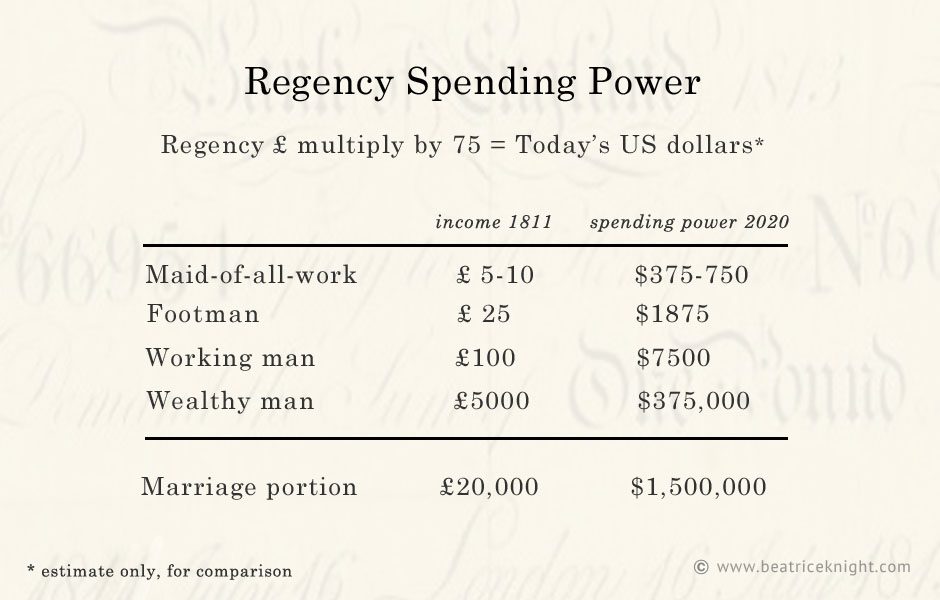

The economic underpinnings of the early 19th century are completely different from those of today, so a mere inflation calculation does not give meaning to the numbers found in Jane Austen’s novels. Clever people like James Heldman have analyzed purchasing power in Austen’s era and found Mr. Darcy with £10,000 a year, and Mr. Bingley with £4,000, would be millionaires by present day standards.

No wonder Charlotte Winford’s family is mortified, in my story Alverstone, when she refuses Mr. Hulkham, a wealthy squire worth £12,000 a year. After five fruitless Seasons, at a time when eligible men were not growing on trees, only a madwoman would reject such a matrimonial prize. To grasp the magnitude of her folly, today’s reader needs a sense of Regency spending power. What kind of lifestyle could £12,000 a year buy—Kardashian level opulence or merely upper middle-class comfort?

While I was researching Alverstone, I compared the cost of goods, labor, travel, land, and rentals between 1813 and 2018/19 and arrived at an average cost of living for each. Then I calculated a conversion rate. I found, if I multiplied Regency income by 75, it was roughly equivalent to US$ Spending Power (with the inflation rate at historic highs in 2022-3, the multiplier is probably 82-84 now). At the 75x multiplier, Charlotte’s suitor Mr. Hulkham would be worth around $900,000 per year. A gentleman with that kind of income, spending the rule-of-thumb 28% on his monthly mortgage payment, could finance $7,200,000 in borrowings. Let’s say his mortgage represents half the value of his property: he could own a $14.4 million estate. Not Kardashian, but pretty fancy.

The take-home? It’s impossible to arrive at an exact formula for converting Regency money to today’s US dollar buying power; my formula is a blunt tool but it offers a quick perspective on relative cost.

Working people in the Regency era could not afford to be pack rats

Regency era supply and demand kept wages extremely low, however in relative terms most goods were pricey and hard to get. There was no planned obsolescence; numerous occupations existed to restore items, from cobblers to upholsterers. Given the high cost of goods , working people prized their possessions. A respectable Sunday best dress and pelisse would cost £6-8 ($450-600); most lady’s maids would count themselves lucky to earn twice that amount per year. A gift like a book or necklace would have been thought an extravagance. In part because goods were so expensive, etiquette forbade well-bred women from accepting gifts from men. What would he expect in return?

The opposite is true today. The average Walmart shopper could not hire full time domestic staff, but can buy “stuff” that gets discarded when it breaks. The value placed on goods has diminished accordingly. Not surprisingly, “designer” brands, celebrity endorsements, and “influencers” have overtaken craftsmanship and materials as a litmus of an item’s “value” in the minds of consumers.

Not surprisingly, only the wealthy could maintain extensive wardrobes during the Regency era. A woman of the beau monde would change clothes multiple times each day, beginning with morning dress, then walking dress if she had an outing, and half-dress for receiving visitors in the afternoon, then dinner dress, and perhaps opera/evening dress after that. When she finally arrived home at two or three in the morning, her lady’s maid would undress her and she would don her nightwear – her sixth change of clothing.

The working poor did not have her problem. They seldom owned more than two outfits: everyday work clothing and Sunday best. Changing clothing for dinner was a sign of social elevation. Recycling was a way of life. Women repaired their slippers, re-trimmed their bonnets and let dresses in and out as they were handed down to family members and finally to a maid, if the family could afford one.

Marriage was an economic necessity

The intense focus on marriage in most 19th century novels was rooted in economics. Typically, a woman of genteel birth was expected to spend her life depending financially on a man: her father or nearest male relative, then her husband. In Alverstone, Charlotte Winford has a fortune of £20,000 (roughly $1,500,000 today). If she does not marry, she will have £800 a year (4% interest on her capital), a sum enabling her to live independently in upper class comfort. The vast majority of 19th century women were not in her position. Mrs. Dashwood and her three daughters had to subsist on £500 in Sense and Sensibility. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet would receive a pitiful £40 per year from her mother’s marriage portion. Regency England was full of impoverished young women who provided wealthy families with a plentiful supply of governesses and companions. Many women married simply to avoid a life of genteel drudgery.

A Middling Household

The wealth gap between rich and poor seems to be with us, no matter the era. In Regency times, the poorest literally owned nothing, while the 1% had unimaginable wealth, much as they do today. But the emergence of a wealthy middle class was causing angst among the old-money ton. Merchants, factory owners, and professionals were buying land from bankrupt aristocrats and setting their sights on marrying into the ranks that despised them. The expanding nouveau riche was a tide that lifted many boats. The ranks of skilled employees, such as clerks, and professionals like lawyers and engineers swelled exponentially through the 19th century, and their solid middle-class households would become the bedrock of a prosperous England.

So what did it cost to run a typical middle class household? Various guides of the time suggest allocating 25% of income for “servants and equipage.” For a healthy income of £1,000 per year ($75,000 in today’s money), staff would usually comprise four female servants, such as a cook, two housemaids (who also doubled as lady’s maids), and a nursemaid; and male servants comprising a footman, coachman, and stable/garden hand. Such a household would keep a carriage and a pair of horses. Upper servants such as a butler, housekeeper, or lady’s maid would be expected of a household with £2,500 a year income ($187,500).

Servants also received their board and keep, plus clothing and apothecary allowances, effectively doubling the amount spent on wages. With a working man’s income of £100, a family was just moving up into the middle class (at £200 they had made it). These households could afford to hire one female maid of all work, but they would not keep a horse and carriage.

The poor of England did not seem eager to stage a Revolution to overthrow their employers, as the French had, maybe because they could hope to move up in the world in an expanding economy.

Sources / Read More

Adams, Samuel and Sarah. The Complete Servant. Knight and Lacey, 1825

Heldman, James. How Wealthy is Mr. Darcy Really? Pounds and Dollars in the World of Pride and Prejudice: JASNA, 1990

Michie, Elsie B. The Vulgar Question of Money: Heiresses, Materialism, and the Novel of Manners from Jane Austen to Henry James. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 2011

Peattie, Antony. The Private Life of Lord Byron. Unbound Publishing, 2019

Toran, Elizabeth. The Economics of Jane Austen’s World: JASNA, 2015