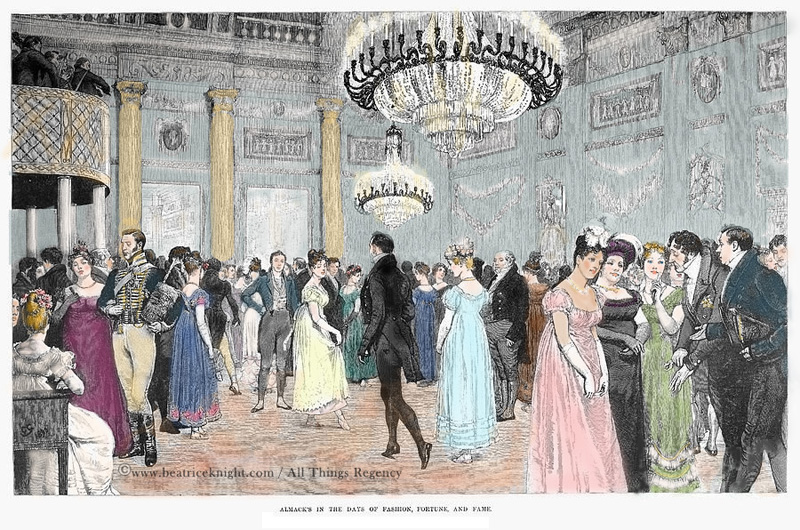

As Ton Central for Regency high society, Almack’s was all about exclusivity. That meant keeping out “mushrooms” (rich social climbers) and other undesirables.

Almack’s – a History

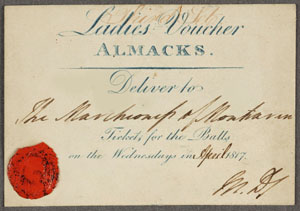

To keep things classy, a cabal of gatekeepers from the highest ranks of society – the Ladies Committee – issued annual (sometimes monthly) vouchers to a closely-vetted list of subscribers. A voucher was a kind of pre-approval, enabling the holder to purchase tickets to balls. They could also bring a guest; those up to snuff were granted “stranger’s tickets.”

Vouchers were printed on heavy card and at about 2.5 x 3.5 inches, they fitted neatly inside a lady’s reticule, or ‘ridicule’ as they tended to be known back then. The example (left), made out to a fictional Marchioness, is based upon a genuine voucher held at the Huntington Library in San Marino, CA.

Being denied a voucher was a social disaster. Almack’s was the ultimate marriage mart, and the ton relied on marriages to expand their wealth and influence. By controlling access to a hand-picked pool of the most desirable matches, the lady patronesses wielded extraordinary power within their caste.

Their tyranny did not stop at destroying the dreams of ambitious mamas. They also imposed sacrosanct rules of dress code, conduct, and admission, as the Duke of Wellington famously learned one evening in 1814 when he showed up late and wearing trousers (the dress code mandated knee breeches). George Ticknor was standing with patroness Lady Jersey when a steward rushed up to inform her that the hero of the Peninsula Wars was cooling his heels at the door. In his first-hand account of the incident, Ticknor later wrote that her ladyship asked the hour and, on hearing it was 7 minutes after 11.00pm, sent the steward back with this reply: “Give my compliments to the Duke of Wellington, and say she is very glad that the first enforcement of the rule of exclusion is such that hereafter no one can complain of its application. He cannot be admitted.”

Almack’s was at the pinnacle of its power from 1810-1820. Accounts of its rise are confusing at best; most are drawn from Gronow’s recollections, written many years after the fact and colorfully embellished. A more thorough understanding of Almack’s evolution can be gleaned now that so many contemporaneous sources – newspapers, letters, diaries, geneology – are digitized. For those interested in a deep dig, this post shares my research and some conclusions I came to (obviously, just my opinion!)

A Tale of Two Assemblies

The true origins of Almack’s Assembly make for a tangled plot: an immigrant’s rag to riches story, a scandalous marriage, a snooty subscription assembly famed for cotillion dancing, a society boycott, a battle for control of a prestigious theater, and the fire that burned down that venue.

In 1763, Lady Elizabeth Bertie, eldest daughter of the third Earl of Abingdon, fell for her handsome Italian dancing master, Giovanni Gallini. She must have been a very determined young woman because: Reader, she married him. He must have been equally determined. Only ten years earlier, he’d arrived in England as an immigrant with no money but some good dance moves. He soon became a principal dancer at the Haymarket Theatre and a sought-after society dance master. By the time he died in January 1805, he was one of the leading impresarios of 18th century England, amassing a large fortune as a majority-owner and manager of the London Opera House (King’s Theatre).

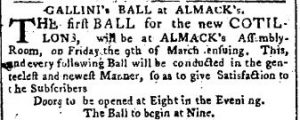

Not everyone admired Gallini’s entrepreneurship. He hosted balls to boost his income and prestige, including the one for the “new cotillions” advertised on February 24, 1770 (right), which was held at Almack’s Great Room. As the years went by, Gallini’s cotillion balls were so popular that he built his own assembly rooms in Hanover Square to accommodate his upper crust subscribers.

In 1788, he became Sir John Gallini when the Pope made him a Knight of the Holy Roman Empire. When he tried to seize full control of the Opera in the thick of a financial scandal, many subscribers became outraged by what they saw as mismanagement and opportunism. Anti-Gallini passions reached such a pitch in 1789 that he was assaulted and booed.

Eventually Gallini’s disaffected subscribers decided to boycott him. Led by the Marchioness of Salisbury, they abandoned Hanover Square en masse and set up their own competing assembly at the Pantheon. When that location burned down, they migrated to Willis’s Rooms in King St. A decade before they held their first ball, “The Assembly in King Street” had been operated by William Almack from 1765 to 1780 in the rooms he built.

Lady Salisbury and her clique adopted that long-established name, Almack’s, for their assembly, set up their own Ladies Committee, and began holding balls in the early 1790s. Their operating model combined the subscription ball concept with that of a private club, in which unsuitable prospects were blackballed. Under their auspices, Almack’s would become the pinnacle of the fashionable world and the hottest ticket in Regency society.

| Date | Assembly | Venue |

|---|---|---|

| 1765-1782 | The Assembly in King Street under William Almack. He manages without a ladies committee. | Almack’s Great Room (later known as Willis’s Rooms) |

| 1783-1791 | Transition period. James Willis takes over the lease, refurbishes the rooms and, in 1785, establishes a committee of “Lady Directresses” to continue the Assembly. The committee ceases its functions in 1790, with the rooms going up for sale in 1791. | Willis’s Rooms |

| 1793-1868 | After hiring Willis’s rooms for their own cotillion balls for a few years, Lady Salisbury and her ex-Hanover Square clique set up their own committee and formally announce the establishment of the “Almack’s Assembly” in 1798 under three “Lady Directresses” – Lady Salisbury, Lady Essex and Lady Malden. This would be Almack’s, as we know it now. | Willis’s Rooms |

The Original Almack

A mythology built up around William Almack, claiming he was a Scotsman whose real name was Macall. Genealogical research and contemporaneous evidence shows the truth to be less dramatic. William Almack, indeed his name, moved from Yorkshire to London around 1752 and set up his first coffee-house in Curzon Street in 1754. He expanded his business in 1759 with an ale-house at no. 49 Pall Mall. This because a popular spot for gentleman’s societies to meet over a good dinner, and in 1762 Almack took over the adjoining building at no.50 and established a private gentleman’s club.

By 1764 the club had split into two separate entities, one of which operated at no.49 under an employee, Mr. Brooks. (In 1778, he would strike out on his own, setting up Brooks club in St James St.) Meanwhile, William Almack went into partnership with Edward Boodle, and the two raked in money from his club at no.50 until 1768, at which point Boodle took over the lease and the club became Boodle’s.

Meanwhile, the entrepreneurial Almack had observed the success of Theresa Cornelys’s subscription balls at Carlisle House, 21A and 21B Soho Square. An actress, Mrs. Cornelys had purchased the venue in 1760, and her events were an instant hit but notoriously trashy. Seeing an opportunity Mr. Almack leased a row of four houses in King Street and built his jewel in the crown, Almack’s Great Room, pitching to a classier clientele.

Meanwhile, the entrepreneurial Almack had observed the success of Theresa Cornelys’s subscription balls at Carlisle House, 21A and 21B Soho Square. An actress, Mrs. Cornelys had purchased the venue in 1760, and her events were an instant hit but notoriously trashy. Seeing an opportunity Mr. Almack leased a row of four houses in King Street and built his jewel in the crown, Almack’s Great Room, pitching to a classier clientele.

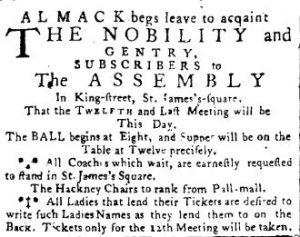

He opened for business in 1765 and hosted 12 subscription balls that year. His May 16 notice in the Public Advertiser offers some insight into how he first operated these. Tickets were sold for each ball and ladies could transfer their tickets by writing the name of the recipient on the back. Advertisements from 1765 to 1780 show “The Assembly in King Street” continued to meet weekly on Thursdays, and some Tuesdays, from late January into April each year.

I found no contemporaneous record of a Ladies Committee steering these assemblies, however Mr. Almack did come up with the novel idea of running one of his profitable private clubs for members of both sexes. He called this venture The Female Coterie, and its founding members are often erroneously cited as the first lady patronesses of Almack’s. The two, however, were separate entities. The Ladies Compleat Pocketbook for 1771 makes this clear, listing in section 3. “The terms of subscription at Almack’s Assembly” which could also be obtained at Mr. Almack’s Pall Mall club; and in section 16. “Rules and orders of the Ladies Coterie in Albemarle Street, with a list of the Members.”

Chancellor E. Beresford seemed to conflate The Female Coterie with the assembly 150 years later when he published his annals of Almack’s in 1922, and his account was faithfully repeated by many writers on the topic. He is not the only writer to have been tripped up by the fact that William Almack owned multiple venues, all of which were named Almack’s, and all of which drew society’s movers and shakers to their gaming tables.

Sidebar – The Female Coterie

William Almack also founded a club named the Female Coterie which first met for dinner and cards at one of his Pall Mall establishments on December 17, 1769 . The founding members were Lady Pembroke, Lady Molyneux, Mrs Fitzroy, Mrs. Meynell, Miss Pelham and Miss Lloyd, who are sometimes incorrectly credited as founding patronesses of the assembly at Almack’s because of confusion over multiple “Almack’s” venues.

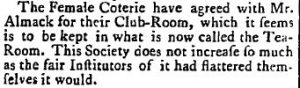

In its first year, the Female Coterie attracted 123 members, including five dukes. Writing to George Montagu on May 6 1770, Horace Walpole described the venture as being modeled on White’s, but allowing both sexes. However, the club did not flourish as expected, and a notice in Lloyd’s Evening Post in May, 1770 places them at “the Tea Room” where, in June one of the Coterie ladies reportedly lost 3000 guineas in deep play.

In its first year, the Female Coterie attracted 123 members, including five dukes. Writing to George Montagu on May 6 1770, Horace Walpole described the venture as being modeled on White’s, but allowing both sexes. However, the club did not flourish as expected, and a notice in Lloyd’s Evening Post in May, 1770 places them at “the Tea Room” where, in June one of the Coterie ladies reportedly lost 3000 guineas in deep play.

There was a tea room at the King Street rooms, so perhaps they met there to play cards in 1770. However, they ended their association with Mr. Almack when they moved to Albemarle Street in 1771, and then to Arlington Street in 1775. Their final meeting was held on December 4, 1777.

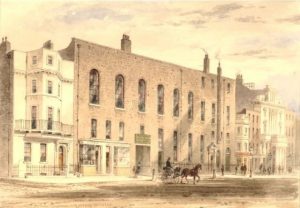

View of the Almack’s on the south side of King Street, St James’s Square, built in 1765. Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Throughout the years William Almack ran the Assembly in King Street, he also hired out the Almack’s Great Room for private balls, regimental events, benefits, and concerts, such as the April 1765 benefit ball held after the opera, with free admission for guests who presented their opera tickets. As was mentioned earlier in this post, Gallini rented Almack’s for his own annual ball in 1770.

William Almack died in 1781, bequeathing the rooms to his son, who struggled to operate The Assembly as usual, and subsequently leased the rooms long-term to his cousin Elizabeth’s husband, Mr. James Willis, who gave the rooms his name.

Willis’s Rooms

After hosting a short season of subscription balls in 1783, Mr. Willis, who also owned the Thatched-Roof Tavern, began a remodel project and held his first ball of the 1784 Season on January 29, assuring subscribers that “no pains or expence has been spared in fitting up the Rooms over Summer, in a new and elegant style, and which, he flatters himself, will meet with their approbation.” He sold subscriptions through the Thatched-Roof and held his assemblies fortnightly on Thursdays. Eventually he brought his son William into the business, and facing stiff competition from other assemblies, it seems possible that the two men sought feminine input on how to make their events a bigger draw.

The First Lady Directresses: Mr. Willis announced a new management model in the Morning Post of January 26, 1785, which included this rejoinder: “N.B. By order of the Ladies (Directresses), no person whatever can be admitted, without producing their ticket; and no Tickets but those of the night will, on any account, be admitted.” The committee continued to play a role through the 1780s. A notice in London World (February, 1789) mentions “the Ladies” ordering alterations to the subscription plan.

1785 also brought new competition from Sir John Gallini, who had built his own “Festino” rooms in Hanover Square and announced his first subscription season. Gallini, a heavy-hitter in entertainments, had an impressive clientele for his cotillion balls. His Assembly, held on Wednesdays, attracted many of society’s leaders.

Willis persevered, adding extras like the masquerade ball in May 1786, but by 1790 competition from other venues had taken its toll and he held only five or six assemblies. The rooms were listed for sale in 1791 by Christie’s. It’s unclear how ownership was resolved but James Willis died in 1794, and his descendants continued to hold a sub-lease on the rooms until some time around 1887.

In the meantime, Sir John Gallini had excited public ire over his management of the Opera House. The issues around this received unflattering coverage in the daily newspapers and he finally announced his intention “to resign his Sceptre’d Sway” in 1789.

It seems likely that Lady Salisbury abandoned the Hanover Square assemblies when Gallini appeared in court before her husband, the Marquis of Salisbury, in an unsavory lawsuit. A ballroom etiquette manual later republished as The Laws of Etiquette by A. Gentleman (1836) claimed : “It should be understood that Almack’s, as it is called, is the Assembly from Hanover Square … The subscribers, through dislike to Sir John Gallini, moved their Assembly, under the influence of the Countess of Salisbury, to King Street, St James’, where the subscription has continued ever since in the name of “Almack’s”.

While I could not verify this particular source, the description of events seems to be borne out by newspaper records. By early 1791, they were planning their subscription ball season at Willis’ Rooms.

The Reign of the Lady Patronesses

The Marchioness of Salisbury by Joshua Reynolds

As luck would have it, the the Hanover Square defectors had stepped into Willis’s Rooms (formerly Almack’s) just as James Willis was trying to breathe new life into his subscription balls. No yearbook exists, alas, for the matrons who made Almack’s the epicenter of Regency society. Under their auspices, Almack’s would be re-invented as the hottest ticket in town: the most exclusive assembly for the most snobbish caste on the planet.

1791-1793: James Willis announced in February 1791 that his subscription balls would commence under the direction of the Duchesses of Gordon and Rutland, the Marchioness of Salisbury, and the Countess of Essex (London Times) Over the next several years, notices confirmed that the balls were still “under the direction of four ladies of the first distinction” but Jane, Duchess of Gordon was absent for the 1793 Season, raising a new regiment in Scotland.

Not all the Lady Patronesses (known as Lady Directresses until 1806) were listed for each ball or season, but multiple notices in the True Briton, London Oracle, Morning Chronicle, Morning Post, and The Times over the following years provide a role-call of sorts:

Sarah, Countess of Essex. 1816 by Charles Turner

1794-1795: Duchess of Rutland, Marchioness of Salisbury, Countess of Essex

1797-98: Ladies Salisbury and Essex (then styled Viscountess Malden ). The voucher system was not yet in place, but there was a List, and a notice on May 29, 1798 decreed: “…those ladies and gentlemen who wish to have Tickets are earnestly requested to send their names to the Lady Directresses… as no person will be admitted but those whose names are on the Ladies Books.”

1799: Duchess of Gordon, the Marchionesses of Townshend and Salisbury.

1801: Duchesses of Devonshire and Gordon, Marchioness of Townshend, Countess of Westmoreland.

1802: For the four subscription balls of the 1802 Season, The Times listed: the Duchesses of Devonshire, Ladies Salisbury and Westmoreland.

1803: Duchesses of Devonshire and St. Albans, and Lady Salisbury.

Sarah, Countess of Jersey by Alfred Edward Chalon.

1804-1811: The Ladies Committee evolved over the years and seemed to vary from five to ten. The Countess of Cholmondeley added her clout in 1805 after the Duchess of Gordon temporarily withdrew, and remained a patroness a decade later. In May, 1806, the patronesses for the season were identified (Morning Chronicle) as Lady Cholmondeley, Lady Gordon, Lady Salisbury, and the Countesses of Kenmare and Westmoreland. Countess Lieven joined the cabal when she arrived in London with her husband, the Russian ambassador, in 1811. And Sarah, Lady Jersey – rapidly emerging as the Queen Bee of London society – became involved at some point over these years.

1812: The “class of 1812” included some of the best known lady patronesses, among them Viscountess Castlereagh, who probably joined the “fair arbiters” when her husband became Foreign Secretary. Various accounts place these women on the committee with her: Countess Cowper, Countess Lieven, Lady Sefton, Lady Londonderry, Lady Jersey, Mrs. Drummond-Burrell, and Princess Esterhazy.

1813-1814: multiple notices in the Morning Chronicle during the 1813 season list the Duchess of Dorset, Countess of Cholmondeley, Lady Salisbury, and Lady Castlereagh as the lady patronesses.

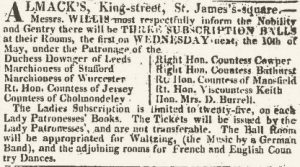

1815: The Morning Post (below), lists ten patronesses on the Ladies Committee for the Season:

The Duchess Dowager of Leeds, Marchioness of Stafford, Marchioness of Worcester, Countess of Jersey, Countess of Cholmondeley, Countess Cowper, Countess Bathurst, Countess of Mansfield, Viscountess Keith, Mrs. Drummond Burrell.

The Duchess Dowager of Leeds, Marchioness of Stafford, Marchioness of Worcester, Countess of Jersey, Countess of Cholmondeley, Countess Cowper, Countess Bathurst, Countess of Mansfield, Viscountess Keith, Mrs. Drummond Burrell.

Mary, the Marchioness of Downshire became involved in 1816, and it is probably her initials that appear on the genuine ladies voucher held by Huntington Library. She remained a patroness until at least 1820. Lady Tankerville is mentioned in a couple of sources as having joined the Committee before 1818.

In addition to its Grand Balls on Wednesdays, which typically had about 400 “persons of distinction” in attendance, Almack’s also held special events. A fancy dress ball late in the 1818 Season drew high attendance, as did the fifth Grand Ball of 1819, for which the Ladies Committee extended entry hours. According to the Chronicle, the result was “a more numerous and brilliant assemblage of distinguished personages than on any former night. Quadrilles and waltzes succeeded alternately and were kept up with an enlivened spirit until four o’clock.”

1820: A bevy of society women were eager to be connected with Almack’s this year, in time for a flurry of events surrounding the succession of the Prince Regent to King, at last. The Ladies Committee probably included: Princess Esterhazy, Ladies Downshire and Cowper and possibly the Countess of Bessborough and Viscountess Granville for a short stint.

Certain special events had their own patronesses, including Countesses Westmeath and Verulam, and Lady C. Stuart Wortley. Almack’s gala event on Monday July 24 was boasted as the “ne plus ultra of fashionable amusement.” While nine “Lady Patronesses” were named: – Princess Esterhazy, The Duchesses of Wellington, Bedford, Hamilton, and Leinster, Lady Downshire, Viscountess Keith, Lady Ann Cullen Smith, Hon. Mrs. Villars – not all were ongoing Almack’s arbiters.

The following Monday, Almack’s hosted a masked ball that assembled another glittering crowd. This one also had its own patronesses: the Duchess of Wellington, Countess of Bessborough, Viscountesses Hampden and Granville, Lady Lamb and Lady Grantham.

A year later, the coronation of King George IV marked the formal end of the Regency Period and an acceleration in the gradual slide that would end Almack’s stranglehold on society by the mid 1820s.

The 1820s: No one seems entirely sure who sat on the Ladies Committee by the mid-1820s, but contemporaneous sources mention a few familiar patronesses: Princess Esterhazy, Ladies Cowper and Jersey, and the now dowager Countess Londonderry (who, in January 1824, denied rumors of her resignation). Lady Cowper, in a letter to Frederick Lamb in March, 1821, wrote that “Almack’s is thin. Nobody likes going before Easter.” Almack’s held the last Grand Ball of the Season on Wednesday July 21, 1824.

Conscious that Almack’s was facing some headwinds, the Ladies Committee responded by cutting back Wednesday balls and adding more one-off glamor events. In June 1825, they drew 700 to an Eastern themed fancy dress fete. It was such a hit that the patronesses immediately announced another fete for the following month.

They continued to tinker with their formula, trying to balance exclusivity with relevance from 1825 through 1829. Ticket prices were reduced, and at some point around 1827, they began closing the doors at midnight. Wednesday balls, now much less frequent, still drew a crowd of 400-500, but the assembly seemed increasing lackluster compared with grand private ballrooms. London had expanded, and the competition for upmarket clientele was tougher than ever.

Some of the “old guard” had clearly jumped ship by 1829. In May that year two of them, Lady Jersey and now dowager Lady Salisbury, held their own balls on the same Wednesday evening as one of the few Almack’s Grand Balls was scheduled.

The 1830s. When King George IV died in 1830 the broader Regency era was over. In hindsight, so was Almack’s, but no one realized that for a few years. In 1833 the Court Journal praised the Wednesday balls that season as “the most brilliant noticed in this distinguished establishment for many years past…” and observed that the recent influx of foreign princes and “illustrious galoppers” had proved ‘refreshing’ for doyennes of King St. The Journal (January 1833) identified Almack’s Committee as a group of seven, comprising “six distinguished English females of high rank associated with a foreign Princess of the first fashion.”

But the momentum did not continue. In 1834 the final Wednesday ball on July 10 was poorly attended. Princess Lieven left England permanently that month after her husband was recalled to Russia, which seemed to be a turning point for the Almack’s Committee. After her departure, James Grant (The Great Metropolis, 1838), identified the Committee members as Lady Jersey, Lady Londonderry, Lady Cowper, the Countesses of Brownlow and Euston, and Lady Willoughby D’Erestry (formerly Mrs. Drummond Burrell). Lady Tankerville was also still a patroness in 1834, according to Benjamin Disraeli’s letters, having held the role since around 1817.

Despite the oversight of these women, Ticknor, commenting on a ball he attended in 1835, found “…no regulation or managing… ” and remarked on a change in the vibe: “…there were fewer of the leading nobility and fashion there than formerly, and that the general cast of the company was younger.” Other observers noted that “few of the ladies of fashion ever go to Almack’s now, with the exception of the lady patronesses who drop in for a few moments to lend it their countenance…”

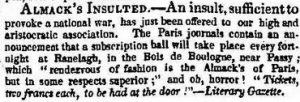

In July 1835, some French parvenu had the nerve to suggest that a Ranelagh assembly in the Bois de Bologne – tickets (oh horror!) two-francs at the door – was “in some respects superior” to the hallowed Almack’s.

In July 1835, some French parvenu had the nerve to suggest that a Ranelagh assembly in the Bois de Bologne – tickets (oh horror!) two-francs at the door – was “in some respects superior” to the hallowed Almack’s.

Almack’s plodded on through the mid-1830’s, mosting hosting benefits like as the Yorkshire Society ball on 22 May, 1835. Although Almack’s Ladies Committee issued vouchers for these events, they played no role in arrangements beyond providing their prestigious rubber stamp. The Almack’s brand still carried weight, and Almack’s balls were also held in the country. Some were merely styled by the name, but others, such as “The First Almack’s Lady Patronesses Ball” held in Salisbury in January 1835, had one-time or current Committee members in attendance.

The Last Hurrah

The decline of Almack’s was, according to a writer in The Quarterly Review of 1840, “clear proof that the palmy days of exclusiveness are gone by in England.” The management vacuum is implied by his remark that there is nothing to prevent people “…from congregating and re-establishing an oligarchy…” The Lady Patroness had never officially resigned, according to Major Chambre, but Almack’s seemed to have no one at the helm.

In the end, nothing contributed more to Almack’s decline than the rise of England’s powerful middle class. Wielding muscle across the political and social establishment as never before, the giants of Victorian industry held their own glittering private balls and worked ceaselessly to marry their daughters into the aristocracy and gentry.

As Almack’s struggled for relevance in the shifting society, it sacrificed exclusivity for attendance and the shine went off its brand. Opinions vary as to when Almack’s finally ended. According to Charles Dickens’ weekly journal, All the Year Round (May 21, 1881): “…after flickering for several years, the wax candles of Almack’s celebrated assemblies went out altogether about 1848…” In fact, balls were held sporadically over the next decade. In 1854, Nathaniel Willis offered this description in his collected prose: “The white relievo upon the pale blue wall of Almack’s showed every crack in its stucco flowers and the faded chaperone who had defects of a similar description to conceal…retreated to the friendlier dimness of the tea room…”

1859 saw a brief revival, with the Court Journal announcing a short season of Almack’s subscription balls to be held on Thursdays, beginning on May 12. In reporting on one of these, attended by 300, four patronesses were named: The Duchess of Richmond, Lady Sefton, Lady Aveland, and Lady Egerton. Four balls were held that year. They marked the last hurrah for Almack’s Assembly. The Ladies Committee was formally dissolved in 1863.

Read More

Anon. The Etiquette of the Ball-Room by A Gentleman. 1823

Ashton, John. Social England Under the Regency, Vol.II. London. Ward and Downey, 1890

Chambre, Major. Recollections of West End Life… Vol.II. London. Hurst and Blackett, 1858

Chancellor, E. Beresford, Memorials of St. James’s Street and Chronicles of Almack’s. London. Grant Richards, 1922

Dickinson, Violet. Miss Eden’s Letters. London,. Macmillan, 1919

Gronow, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow

Ladies Compleat Pocket Book for 1771. London. Carnan and Newbury, 1770.

Luttrell, Henry. Advice to Julia. London. John Murray, 1820

Ticknor, George. Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor. 1876

Wheatley, Henry B. London Past and Present. London. John Murray, 1891

Yates, G. The Ball; Or a Glance at Almack’s in 1829. London. Henry Colburn, 1829