By 1800, the East India Company ruled one-fifth of the world and deployed an army larger than England’s to protect its network of forts and trading posts. Like a sovereign state, it minted currency, collected taxes, and administered justice. Trading in spices, textiles, saltpeter, tea and opium, it became the world’s largest company and charted the course of British colonial empire-building for two centuries.

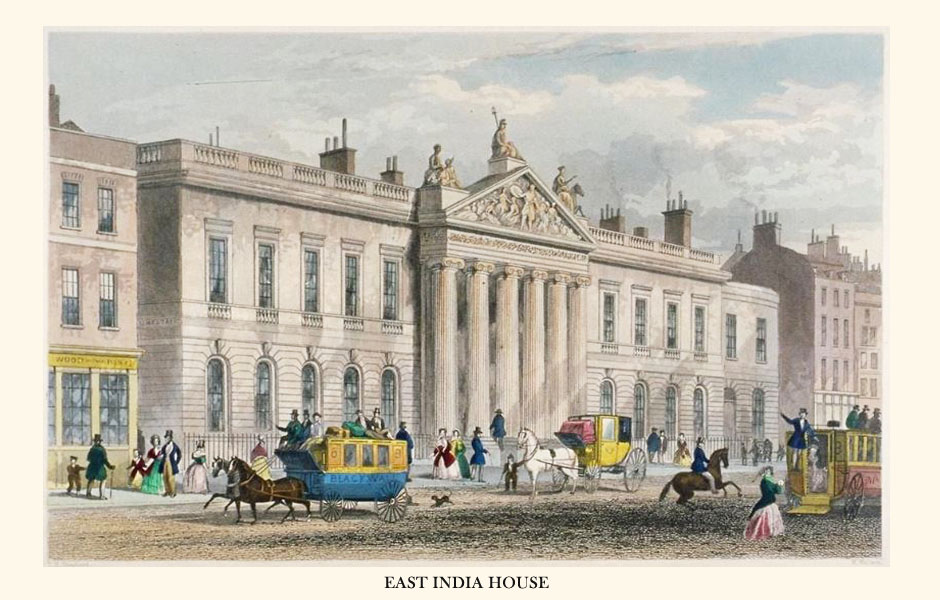

The East India Company

In 1788, parliamentarian Edmund Burke called the East India Company “a state in the disguise of a merchant.” By then, its trade in spices, textiles and opium had made the company a juggernaut. It endured for 274 years, which is longer than a good many nation states, and became the world’s largest company. Its army numbered over quarter of a million men. In a roundabout way, its aggressive trade practices led to the American Revolution, when the Company was granted the rights to sell tea from British colonies in Asia to American buyers, giving it a commercial advantage over colonial American tea importers. This favoritism led to the Boston Tea Party, which triggered events that culminated in American independence.

A few key dates in the Company history:

- 1600 – Queen Elizabeth I granted merchants the right to trade in the East Indies. A small group banded together on a venture.

- 1601 – calling themselves the ‘Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies,’ they set sail.

- 1603 – their 4 ships returned carrying 500 tons of pricey peppercorns; they were in business.

- 1657 – they incorporated

- 1669 – the king granted the Company control of Bombay (a dowry gift to him from Portugal).

- 1709 – the Company finally merged with its part-owned nuisance rival.

- 1757 – they conquered Bengal, India.

- 1765 – began taxing 10 million Bengali people, twice the population of England.

- 1770 – had its own financial crisis and a government bailout in 1773.

- 1773 – Boston Tea Party – colonists threw tea overboard to prevent the Company controlling the tea trade in the US.

- 1784 – the India Act (1784) gave the British government “dual control” over India and forbade the Company to “pursue schemes of conquest and extension of dominion in India.”

- 1813 – the Charter Act ended the Company’s trade monopoly with India.

- 1833 – ceased to trade and became a territorial administrator.

- 1839 – China tried to end the Company’s domination of the opium trade. The Opium Wars began.

- 1857 – the Indian Rebellion. The Company’s brutal response was more than a PR disaster.

- 1858 – handed over its administration of India to the British government, marking the start of the British Raj.

- 1874 – the British government nationalized the Company assets, and it was dissolved.

It’s tempting to write a book on the extraordinary rise of the company to pseudo-sovereign status, but weightier intellects than mine have already furnished some excellent reads (see end of post), and I plan to explore aspects of the Company in other posts.

Read More

Bayly, C.A. (1988) The New Cambridge History of India: Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press.

Bowen, H. V. (1991). Revenue and Reform: The Indian Problem in British Politics, 1757–1773. Cambridge University Press.

Burke, Edmund. (1909). Speeches on the Impeachment of Warren Hastings, 2nd ed. Bangabasi Press.

Chaudhuri, K. N. (1978). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660–1760. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Collins, G. M. (2019). “The Limits of Mercantile Administration: Adam Smith and Edmund Burke on Britain’s East India Company” Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 41(3), 369–392.

Finn, Margot; Smith, Kate, eds. (2018). The East India Company at Home, 1757–1857. London: UCL Press.

Sutherland, Lucy S. (1952). The East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.