By the time Regency modiste, Madame Lanchester was jailed for bankruptcy in Marshalsea Prison on February 8, 1812, she had spent more than a decade as one of London’s best known milliner/dressmakers. Unfortunately, her flair and big ideas were not matched by her head for business.

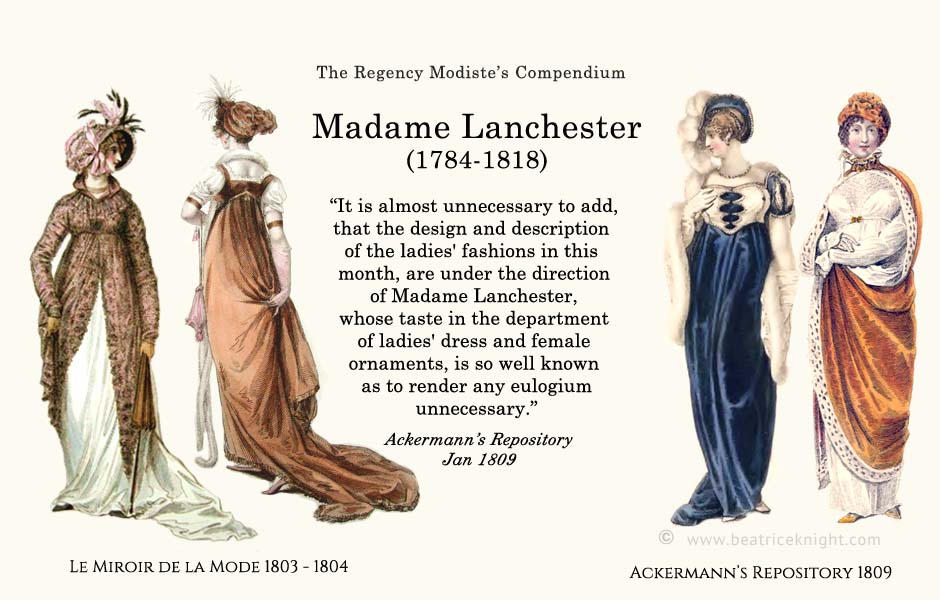

Margaret Ann Lanchester (1784-1818)

1800-02: 37 Sackville St.

1803-05: 17 New Bond St.

1806-10: 59 St. James St.

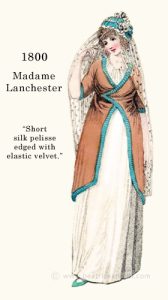

Margaret Ann Lanchester had big ideas, talent, and a love of fine clothes. Inspired by Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion, to which her mother had subscribed in 1798-99, she set up shop in Sackville Street at age 16, styling herself initially as “Mrs.” for gravitas, then rapidly adopting “Madame,” a trendy affectation among Regency milliners and dressmakers. Despite her inexperience, she built a reputation for tasteful distinctively haut ton attire that flattered womanly figures. Several of her earliest designs were featured in Richard Phillip’s Fashions of London and Paris, in April and August, 1800.

Margaret Ann Lanchester had big ideas, talent, and a love of fine clothes. Inspired by Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion, to which her mother had subscribed in 1798-99, she set up shop in Sackville Street at age 16, styling herself initially as “Mrs.” for gravitas, then rapidly adopting “Madame,” a trendy affectation among Regency milliners and dressmakers. Despite her inexperience, she built a reputation for tasteful distinctively haut ton attire that flattered womanly figures. Several of her earliest designs were featured in Richard Phillip’s Fashions of London and Paris, in April and August, 1800.

To make a splash with the right kind of clientele, Lanchester had to work in rich, beautiful fabrics. She ordered on credit, gambling that sales would keep her afloat, however her shop struggled to turn a profit and she was forced to auction off her entire stock in April 1802 to pay accrued debts. A month later, probably in a bid to smokescreen her financial embarrassment, she inserted a notice in the Morning Post denying supposed rumors that she intended to move permanently to Paris. When she still hadn’t paid off her creditors by the end of the year, she was declared bankrupt in January 1803.

Possible portrait of Margaret Ann Lanchester. Arthur William Devis. ca 1802. British Museum

As luck would have it, she hooked up with a Devis

Sometime in 1802, her path had crossed with members of the Devis family of painters, notably Arthur William Devis (1762-1822). Devis’s first wife visited Madame Lanchester’s shop in Sackville St. at least once during 1802 (a bill of hers dated Dec 18, 1802 for gowns, dresses and petticoats was among the papers of John Biddulph, Devis’s patron). 40-year-old Devis must have accompanied her, and was apparently smitten with 18-year-old Lanchester.

By mid-1803, the financially feckless Devis was paying Lanchester’s bills and, with his support, she regrouped after her bankruptcy and opened a new marchand des modes shop at 17 New Bond St. with his sister, Ann Devis. Around this time Devis dashed off the portrait of an unidentified young woman (left) in pen and brown ink, which could well be that of Lanchester, sketched in the manner of a fashion plate just before he began the detailed illustrations for her forthcoming magazine. The tight sleeves and styling of the dress are characteristic of women’s morning and walking dresses in 1802/03.

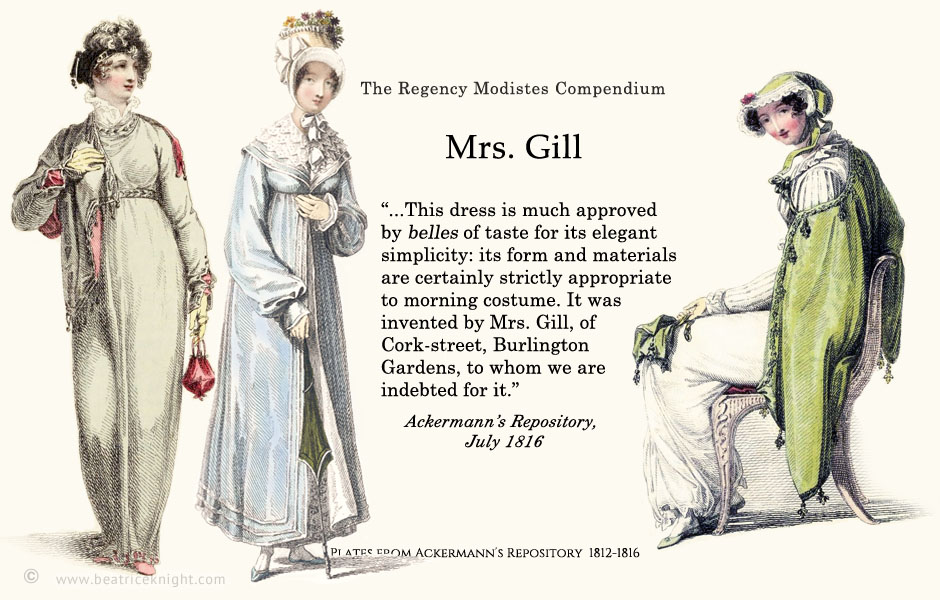

‘The prevailing Spring Fashions for 1806…the Elegant designs of Madame Lanchester’ by James Mitan, after Arthur William Devis… La Belle Assemblée, June 1806

To promote her new venture, Lanchester founded Le Miroir de la Mode, a glamorous but short-lived magazine that featured some of the most stunning fashion plates published in the 19th century. Arthur Devis is believed responsible for its fine illustrations based upon a plate of Lanchester’s fashions (right) for which he received published credit in 1806. (The resemblance to those in Le Miroir is apparent). Common sense suggests Lanchester, and probably his sister Ann, modeled for at least some of his engravings.

Le Miroir was a very expensive publication, and did not generate sufficient revenue to cover costs. Unable to pay Lanchester’s debts, Devis found himself in debtor’s prison early in 1804. He was bailed out by his long-suffering patron John Biddulph in July and undertook to get his affairs back on track. To some extent he did, selling paintings and repaying some of the money he owed Biddulph. He finally married Ann Lanchester in September, 1806, and she moved her shop to St James St.

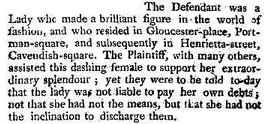

Finances remained a problem for the couple.  In December 1807, Lanchester took legal action against a deadbeat client, claiming to have “assisted this dashing female to support her extraordinary splendour.” The woman disclaimed liability and while she had the means to pay her bills, the court heard she “had not the inclination to discharge them.”

In December 1807, Lanchester took legal action against a deadbeat client, claiming to have “assisted this dashing female to support her extraordinary splendour.” The woman disclaimed liability and while she had the means to pay her bills, the court heard she “had not the inclination to discharge them.”

The judge dismissed Lanchester’s suit, finding that: “Madame Lanchester had not much reason to complain; she knew the way of life to which the Defendant was devoted, and all the risks incident to such a situation.” No wonder London’s more pragmatic dressmakers usually stated their terms as “ready money” only. It seems that Lanchester had been naïve. Having equipped one of London’s most extravagant demi-reps with an expensive wardrobe on terms of credit, she was viewed unsympathetically by the court as little more than a knowing accomplice to her client’s “way of life” (read: upscale prostitution).

After losing the court case, Mrs. Lanchester continued to design beautiful gowns and tried to revive her magazine. When that did not pan out, she contributed her unused plates to Rudolph Ackermann, who was about to launch his new Repository of Arts. The first issues in January-March, 1809 featured Lanchester’s designs. For most of that year, she was in and out of creditors meetings and making “dividend” payments. After holding an end of season sale in October 1809, she closed her business for a few months, probably to give birth to her elder daughter Ellin, named after one of Devis’s sisters.

Balancing motherhood with the demands of her struggling business took its toll. Madame Lanchester re-opened briefly in March 1810 for a going-out-of-business-sale and was in bankruptcy proceedings through the rest of the year. Her “commission of bankruptcy” was finalized on July 17, 1811 (National Archive). In February 1812, just four months after her second daughter Isabella was baptized, Mrs. Lanchester went to debtors’ prison. She was eventually discharged on the 1st Jan 1813 on the surety of her husband.

She did not go back into business, but remained at home caring for her two girls. Oddly, both girls were baptized together at St. Giles for the second time in the New Year of 1817, despite previous baptisms in Westminster parish. Madame Lanchester died aged only 34, in Nov 1818 at the family home in Caroline St, Bedford Square and was buried in the family plot at St Giles in the Fields Churchyard on 2 Dec 1818.

While she was in business, she had trained an apprentice, Mrs. Osgood, who set up her own store in Lower Brook St. Grosvenor Square around 1810. She advertised as Madame Lanchester’s successor and protegee and promoted her designs in the Ladies Monthly Museum of April, 1812. I have not ascertained Mrs. Osgood’s fate.

Connection to the Bride of Frankenstein

From rummaging on Ancestry.com, I found Mrs. Lanchester may be connected to some interesting descendants. Her brother, thought to be a vicar, adopted two children (Fredrick and Mary) who were depicted in Arthur Wm. Devis’s portraits The Age of innocence and Infantile Amusement. There is some hint that children may have been born to Mrs. Lanchester, out of wedlock, before she married Arthur Devis, or that they belonged to her sister-in-law, Ann Devis.

Among Frederick’s descendents are Frederick Lanchester, best known for designing and building the first all-British motor car in 1895. His sister, Edith Lanchester, was a suffragette and radical, who committed the gender crime of being “over-educated” and was pronounced “insane” at the behest of her father and brothers when she refused to marry her lover. Edith was bound and dragged into a horse-drawn carriage which took her to what is now The Priory clinic.

Her case caused a sensation and prompted the New York Times and various public figures to demand her release. After pressure from her landlady and local Member of Parliament, the doctors revised their opinion, finding her “sane but foolish.” She was released and never spoke to her father again. Her daughter was Elsa Lanchester, the actress who co-stared in the Bride of Frankenstein with Boris Karloff.

Read More

La Belle Assemblée. London. J. Bell.

Le Miroir de la Mode. London. A. Lanchester.

Paviere, S. (1936). Biographical Notes on the Devis Family of Painters. The Volume of the Walpole Society, 25, 115-166.

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann.