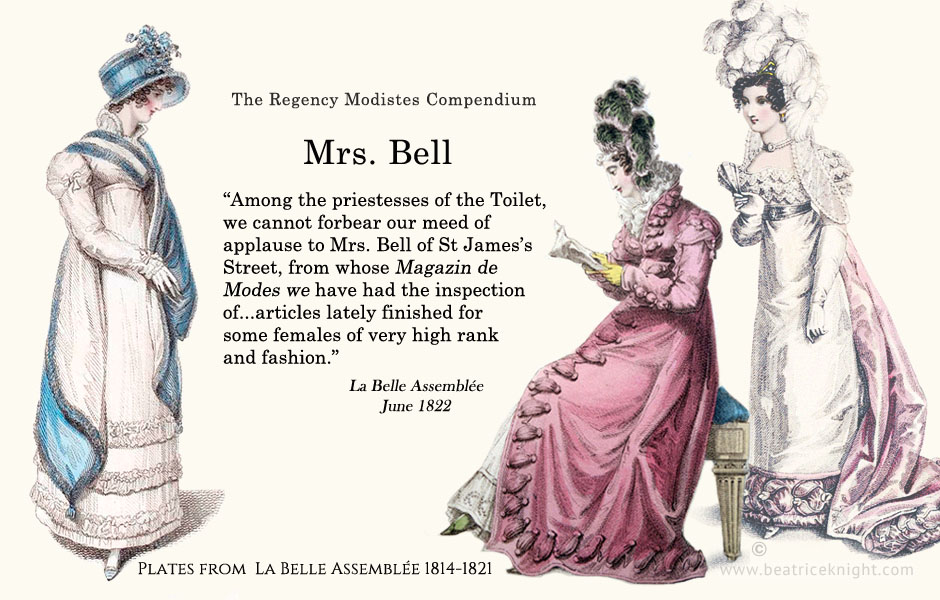

Fond of declaring herself the inventress of this or that fashion, Mrs. Mary Ann Bell was not above purloining designs from other magazines and calling them her own. She was the great survivor of the Regency modistes. No slouch in self-promotion, she saw the rise of a wealthy middle class as an opportunity, and was never so exclusive in her clientele that she went broke waiting for impoverished aristocrats to pay their bills.

Mrs. Mary Ann Bell nee Millard (1786-1835)

1813-14: 22 Upper King St.

1814-18: 26 Charlotte St. Bedford Square

1817-30: 52 St. James St

1830-35: 3 Cleveland Row

Mary Ann Bell could be called the great survivor of the Regency modistes. Her presence was a constant for most of the era. She quite literally worked until she dropped. Through the lens of 21st century perceptions, Mrs. Bell sometimes receives a bad rap for using her husband’s business to leverage her profile, as if none of today’s celebrities are guilty of that!

The fact remains that at a time when middle-class women were discouraged and prevented from seeking a life outside of marriage and family, Mrs. Bell was an entrepreneur who built a successful business of her own, and trained numerous other women in skills that gave them earning-power.

The infamous Bell family rift

Mary Ann Millard, who may have been a daughter of the Millard family ‘East India Warehouse’ owners, married her husband John Browne Bell in 1806, and they had their first child, John William, a year later. It would be another six years before their daughter Jane arrived late in 1813. By that time her father-in-law, John Bell (1745-1831), one of the original owners of the Morning Post newspaper and founder of the 50,000 volume ‘Bell’s Circulating Library,’ had launched the upscale La Belle Assemblée in 1806. It rapidly rose to become one of the most influential women’s fashion magazines of the era.

Mrs. Bell would become its fashion editor in 1811, however she and her husband would have to eat crow before her father-in-law gave her the nod. Hubby, John Browne Bell had fallen out with his father when he partnered with John De Camp to launch Le Beau Monde in November 1806, just nine months after Bell senior launched La Belle Assemblée in February.

Bell Jnr must have known how his father would react to seeing him launch a magazine in competition with Bell senior’s long-planned jewel-in-the-crown. To add insult to injury, he had entered a business partnership outside of the family. Were these rash decisions an effort to prove himself and impress his new wife? Or had he expected his father, aged 61 in 1806, to hand him the keys to the kingdom and conveniently retire.

Perhaps he had expected to be granted a key role in the prestigious new magazine and was then piqued when Bell senior exercised full control. Whatever his motivation, his independent business venture did not pan out. Le Beau Monde was expensive to produce and never gained sufficient circulation to sustain itself. In April 1809, Bell Jnr off-loaded the magazine to J. Tyler, who kept it on life support until it folded in April 1810. Bell Jnr had also launched the National Register with partner De Camp in 1808. It also bombed and he was certified bankrupt in June 1810.

His financial mess must have galvanized his young wife, Mary Ann Bell. By the time 1811 loomed, something had to be done to keep their household afloat. Clearly the rift with John Bell senior had to be patched up.

It’s not clear how the Bells got back on talking terms. Common sense suggests that either John Browne Bell went cap-in-hand, needing to provide for his family, or Mary Ann reached out, as mother of Bell senior’s grandchildren. Perhaps she saw the chance to kill two birds with one stone and offered her services to help her father-in-law with the workload of La Belle Assemblée. John Bell was always an innovative thinker and quite a risk-taker. He may have thought a woman could bring something extra to the table, and Mary Ann certainly appeared to have the chops his son lacked.

In addition to throwing his son’s family a financial life-line, pragmatism may have factored into Bell Snr’s decision to bring Mary Ann on board. La Belle Assemblée’s plodding, pedantic fashion pages needed a make-over. Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts was stiff competition; his fashion plates were superior, and his editorial more stylish.

One fact is indisputable: after years of hostility, John Bell suddenly handed control of La Belle Assemblée’s fashion pages to his daughter-in-law. It did not happen in a vacuum and it set the stage for the next phase in Mrs. Bell’s career and family life.

Mrs. Bell becomes editorial director of La Belle Assemblée

In Women in Print (Faber & Faber, 1972), Alison Adburgham states: “The decade from 1810 to 1820 is considered to be the greatest period of La Belle Assemblée and during these years the fashion department came under the direction of Mrs. Mary Ann Bell.”

I’m going to go out on a limb and assign a date to Mrs. Bell’s takeover. Based on style and content, I believe “Fashions for August 1811” (published in the July, 1811 issue) was her first stab at the column, and probably a try-out to win Bell Senior’s approval. Based upon a comparison of editorial styles, she took over directorship three months later, with the October issue, writing the column: “Fashions for November, 1811.”

I believe the September, 1811 issue may have been the last penned by her Mr. Collins-like predecessor. He wrote: “During the last month, we have observed several little elegant trifles, but nothing strikingly new or decidedly prevailing.” Farther along, remarking on a Morning dress that is “very fashionably prevailing,” he explains that it conveys the “neatness, delicacy and innocence, always interesting in a female… a well regulated mind, conduct marked with propriety…and all those qualities so requisite for the well arrangement of a family.”

Such claptrap would never have made it past Mrs. Bell. 1812 marks the year she set her stamp on La Belle Assemblée, opening the January fashion pages in true Mary Ann style, with: “Hail, Goddess of versatile attraction, changeful idol of the rich, the beautiful, and the young! Thy full influence now is felt in this our gay metropolis, and myriads follow thy splendid car, attached in willing bondage by thy silken bands…”

Mary Ann’s columns dished out flowery language and dollops of romantic imagery, lavished women with flattery, and were more gushy and readable than those of her predecessor. Before she took the helm, the editorial was generally judgmental in tone, patronizing, impersonal, and boring. She could not resist the opportunity for vertical integration: during her pregnancy in 1813,she set about establishing her “Salon of Fashion” which she launched around February 1814 at 22 Upper King St. Around August of that year, she moved her Magazin des Modes to Charlotte Street – much more elegant.

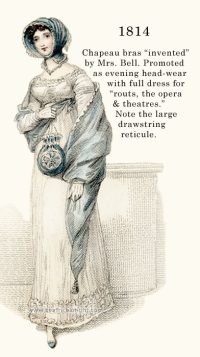

In March 1814, Mrs. Bell, looking to differentiate herself from competitors, began promoting her “invention” of a “ladies’ chapeau bras” in the Morning Chronicle. This “indispensible” new head dress was featured in her first fashion plate, published in the April issue of her father-in-law’s magazine (see lightbox images in Fashion Sensibility section below).

Her designs appeared in almost every issue of La Belle Assemblée from then on, until John Bell senior retired in 1821. Naturally she and her shop were lavishly praised in the accompanying editorial – which she authored. For many years, the column’s major sponsor was Urling’s lace.

Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 18 May, 1817.

Almost as soon as she launched her business, Mrs. Bell saw the threat of warehouse competition, and realized that she had to market accordingly. Unlike many upscale modistes, she had no qualms about discounting and targeting women who would never be admitted to Almack’s. The 1817 example (left) pitched openly to budget conscious customers, promising her goods at prices “cheaper than any other person can possibly sell them” and promoting her mail-order service to the provinces.

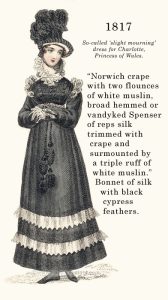

Later in 1817, Mrs. Bell adopted a different tone in La Belle Assemblée (below) when pandering to the delicate sensibilities of her beau monde clientele.

Corsetry

From the outset, Mrs. Bell found corsetry a profitable niche. In August 1814, she featured a Circassian corset “which gives relief and protection to pregnant ladies.” The style had been around for a long while, but she added her touches and claimed credit as the ‘inventress.’ Having recently given birth, she seemed mindful of the concerns of young mothers about body-image and posture – perhaps she had issues of her own. It seems likely that she held strong (and unusual at the time) opinions on breast-feeding, writing about the morning dress promoted in the same issue (right) this reassurance: “We are certain no lady on first seeing this elegant dress could possibly surmise the purpose for which it was designed, that of enabling a lady to suckle her own child…”

From the outset, Mrs. Bell found corsetry a profitable niche. In August 1814, she featured a Circassian corset “which gives relief and protection to pregnant ladies.” The style had been around for a long while, but she added her touches and claimed credit as the ‘inventress.’ Having recently given birth, she seemed mindful of the concerns of young mothers about body-image and posture – perhaps she had issues of her own. It seems likely that she held strong (and unusual at the time) opinions on breast-feeding, writing about the morning dress promoted in the same issue (right) this reassurance: “We are certain no lady on first seeing this elegant dress could possibly surmise the purpose for which it was designed, that of enabling a lady to suckle her own child…”

At the time, breast-feeding was unusual among upper class women. Perhaps Mrs. Bell had decided to nurse her own baby daughter, juggling her business demands with a feeding schedule. It seems possible that she created the morning/nursing dress for her own use, initially.

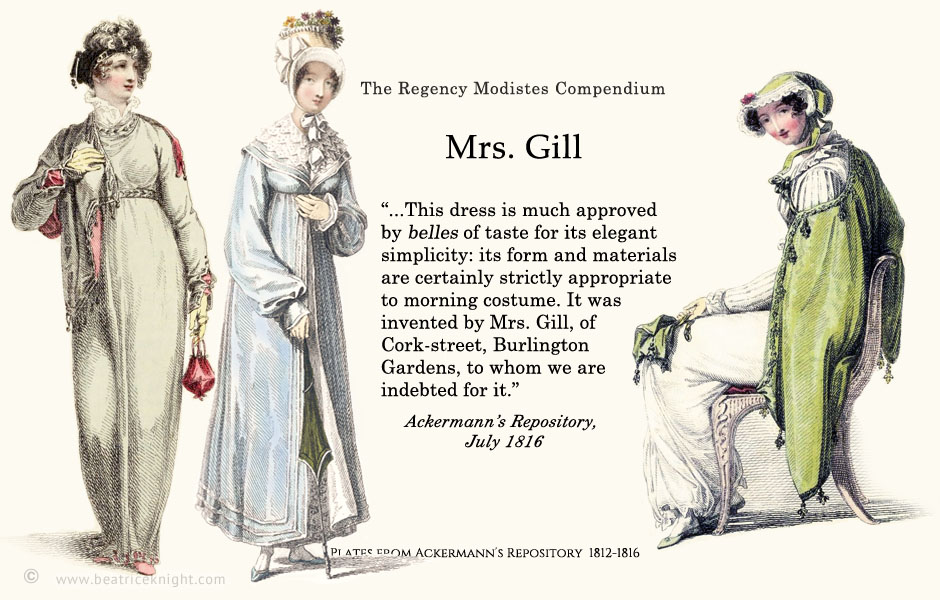

Along with the ‘chapeau bras,’ the ‘Albion cap,’ and the ‘new hoop’ for court dresses, Mrs. Bell ‘invented’ various corsets to differentiate herself from better-known modistes of the day like Mrs. Gill and Mrs. Bean. Eventually, when the fashion tide turned toward structured bodices and cinched waists in the 1820s, she had already made herself a household name as a classy corsetry maker, and expanded that side of her business to cater for the new silhouette.

Mourning

Mourning

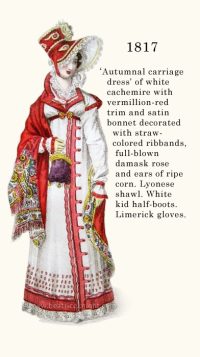

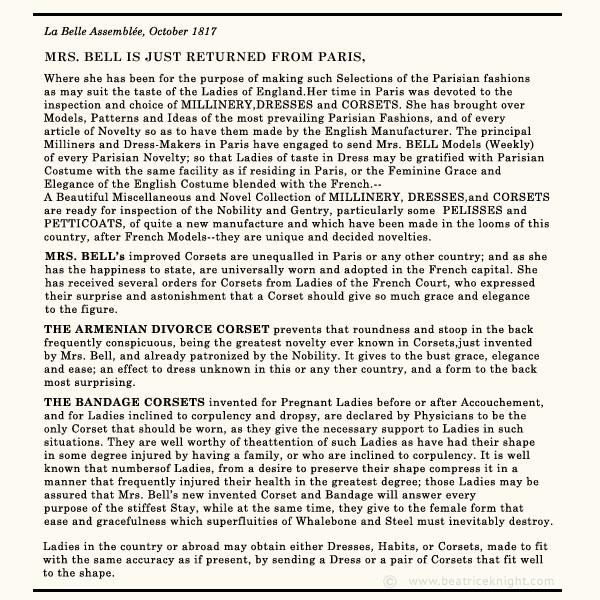

Mrs. Bell’s astute eye for niche opportunities also drew her to mourning. She carried an unusually high stock of mourning accessories in her shop, along with ready-to-wear mourning costume and hats that could quickly be adjusted for taste and fit. At a moment’s notice, she was ready to advertise her range in newspapers, and she kept a set of fashion plates ready just in case. Her planning paid off in 1817 when the young Charlotte, Princess of Wales died tragically in childbirth. Not only did Mrs. Bell have months of full- and half-mourning designs ready to roll-out in La Belle Assemblée, she had plates to spare and seized the chance to grab the December 1817 promotion space in Ackermann’s Repository, after they were caught flat-footed with nothing to replace the fashion spread planned for that month.

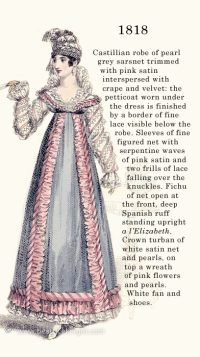

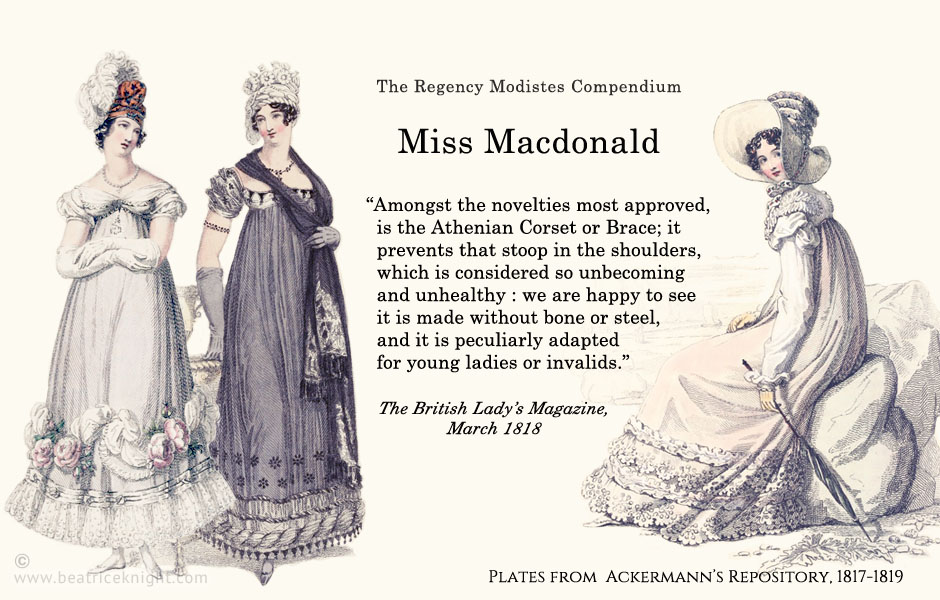

Miss MacDonald – a rival of Mrs. Bell’s, had purchased most of the promotion space in Ackermann’s from September 1817 through June 1818, but when her December designs had to be bumped, she had no full-mourning plates ready to replace them. While she rushed to prepare half-mourning designs for the January 1818 issue, Mrs. Bell pounced on the spots left open in the reshuffle. No doubts she received these at a hefty discount; after all, she had spared Rudolph Ackermann the embarrassment of going to press without a suitable mourning fashion spread.

Seaside Trunk Shows

Seaside Trunk Shows

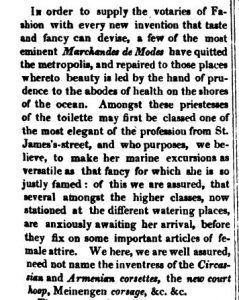

When the royals headed to Scotland and the beau monde quit hot, smelly London for their autumnal retreats, sensible modistes like Mrs. Bell did not hang about the deserted West End. They set up temporary shop where their well-heeled clientele gathered, in resort towns like Brighton, Cheltenham, and Scarborough. Mrs. Bell described this venture in her September, 1818 column (right), modestly referencing herself as “the most elegant” among the “priestesses of the toilette” to repair to these watering places.

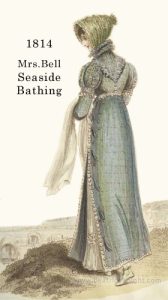

From La Belle Assemblée, August 1814. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight.

Mrs. Bell had been making seaside clothing ever since she opened her business, carving out a successful niche in bathing dresses and seaside promenade gowns, which she exhibited in trunk shows and display booths in market squares. She promoted her “Circassian Ladies’ Corset and Sea Side Bathing Dress” in August, 1814, among the first designs she published. She continued to promote seaside fashions most years after that, taking her trunk show on the road.

In September 1822, when many fashionable people had been at the king’s birthday court at the Palace of Holyroodhouse and were meandering through various spa towns afterward, she opened a Magazin de Haut Mode in Scarborough and then returned to town in time for Christmas with her family.

Change was afoot at her father-in-law’s fashion magazine that year. After a lifetime as a publisher and media magnate of his time, John Bell senior knew his market very well. He must have observed the trends that would ultimately kill magazines of “elevated tone” like La Belle Assemblée. He was also semi-retired late in 1821, and his son, helping with the ownership transition to Geo Whittaker, had obviously tried to make the publication more profitable during 1822, including adding promotional spots from fashion warehouses like Dison Wilson & Co. Mrs. Bell was still writing the fashion spread, but her name was not promoted as it had been. Perhaps Mr. Whittaker, hoped to attract other advertisers if the fashion pages were no longer a transparently dedicated to boosting Mrs. Bell’s fashoin brand.

It’s easy to imagine Mary Ann Bell sitting down of an evening with her husband, once their three children were in bed, to discuss their challenges. For her, the increasing rise of fashion warehouses was making the fashion business very tough. It’s clear that she and her husband would have to make some adjustments.

As of April 1823, G & WB Whittaker took over formally as publishers of La Belle Assemblée after a two-year transition period in which the Bell family had maintained a proprietor’s interest in the business. Mrs. Bell and her husband were by then planning a new fashion-focused magazine to be launched in 1824: The World of Fashion and Continental Feuilletons. This would feature a dazzling array of Mrs. Bell’s designs in glamorous plates, along with her distinctively gushy editorial. While the magazine was almost certainly funded by John Bell senior, Bell junior was in the publisher role from the get go, as evidenced by the frontispieces.

Mrs. Bell’s Fashion Sensibility

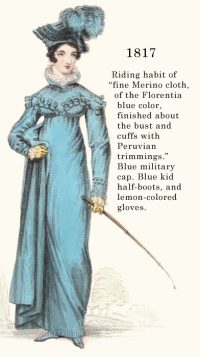

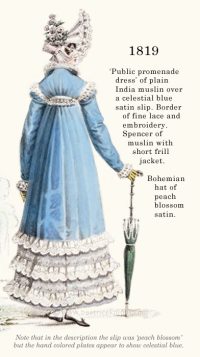

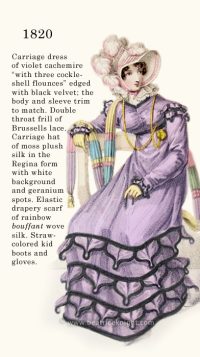

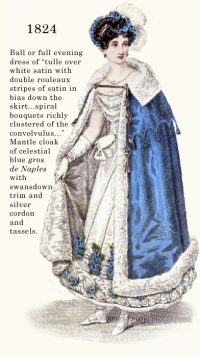

Of the Regency modistes, Mrs. Bell’s published designs span the longest timeline, by far – covering over 20 years. In the course of her career, British women’s fashion went through a major transition. The soft, neo-classical lines and Empire silhouette were consigned to history and the Romantic era steered fashions to a natural waistline, puffed sleeves, and ever-widening skirts.

Between 1825-28, this look went on steroids. Gigot or leg-o-mutton sleeves were puffed out with expanders and mini-hoops until they appeared to be twice the size of the waist, and skirts were so voluminous that gores were not enough, so extra fabric was gathered into the waistband. The Romantic sensibility seemed custom-made for Mrs. Bell’s personal tastes. She had a penchant for frills and flounces, which made many of her designs appear over-worked when simpler tastes prevailed in the 1810s. She also had a major sponsor to please – Urling’s lace – and seldom missed a chance to showcase their product.

In her countless self-referential fashion columns, Mrs. Bell branded herself as a maker of tasteful and elegant attire for upper echelon women. A few examples of her messaging from La Belle Assemblée:

September, 1814: “Mrs. Bell, whose correct and elegant taste enables her to new-model the Parisian fashions in the most becoming manner…”

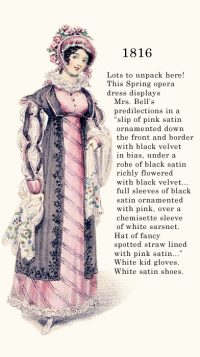

April, 1816 – praising her shop: “…we call the attention of our fair readers…to the highly tasteful Magazin des Modes, Charlotte-street, Bedford-square, now resorted to by the haut ton as a morning lounge…”

July, 1818: “Mrs. Bell, who, from her genuine taste…may be deemed one of our first arbitresses of the toilette…”

July 1821: “…Mrs. Bell, whose elegant and classical taste confers so much honour on herself, and adds to the charms and graces of the exalted females by whom she is patronized.”

While Mrs. Bell routinely claimed to have “invented” the fashions she promoted, she was not above purloining French designs and calling them her own. This was not easy to do during the war with Napoleon, when sources of information about Paris fashions dried up. After Waterloo, however, she drew “inspiration” quite often from the French magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, recycling designs virtually unaltered. Her November 1815 design for La Belle Assemblée, which her fashion editorial claimed “…may be ranked among the happiest inventions of Mrs. Bell…” had appeared a couple of months earlier in the Journal des Dames.

THROUGH THE YEARS – click to enlarge

Copy-cat or Inspired?

Copy-cat or Inspired?

Mrs. Bell was not always the most original fashion creator. Many of her designs draw inspiration from other fashion plates, but I have not seen exact copies. She was wise enough to purloin a concept and tweak the detailing to suit her customer preferences and brand identity.

The promenade costume (left) is an example of her approach. At first glance, the 1819 fashion is strongly suggestive of the French design published six years earlier. However, virtually every detail is different. I would not call Mrs. Bell’s design a copy, but she seems to have drawn from the 1813 design to create an updated English version of the look.

Finances

As the 1820s continued, middle class prosperity expanded the market for high-end clothing, but competition for that market also exploded. At a time when every dress demanded voluminous amounts of fabric, modistes like Mrs. Bell had to carry a costly inventory, and could ill-afford to offer the generous credit terms the “nobility and gentry” continued to expect. Neither could they claim a stranglehold on quality when fashion warehouses – the predecessors of department stores – offered appealing ready-to-wear collections and inexpensive made-to-order and alteration services. Middle class women were disinclined to pay a fortune for a snooty modiste to look down at them, when they could dress like a queen – and get treated like one – for half the price.

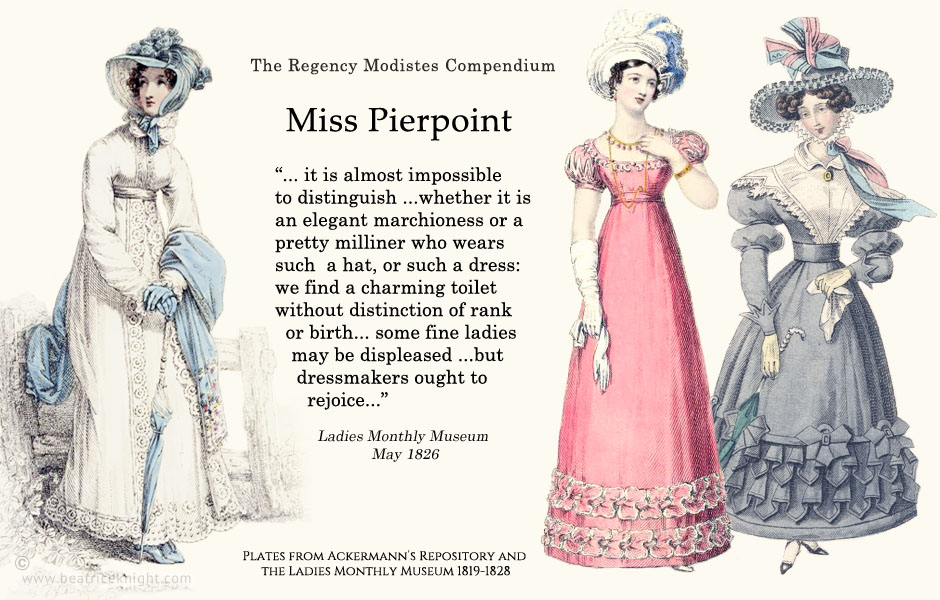

Mrs. Bell, unlike most of her competitors, had the backing of a prosperous husband and was willing to take a debtor to court. She did so on more than one occasion. She was also broad enough in her focus to cater to different market sectors, which enabled her to compete more effectively than her main rival in the 1820s – Miss Pierpoint. No other modiste enjoyed the huge advantage of “free” media; the World of Fashion kept her name at the top of the list of classy fashion shops for clients who preferred to avoid the stares of warehouse clerks and be dressed instead by a real modiste.

Mrs. Bell outlasted Miss Pierpoint. Perhaps she even purchased some of that lady’s discounted stock at her final bankruptcy auction in 1832. By then, Mrs. Bell was suffering health issues. She had worked on the magazine through 1831, but appeared to relinquish her columns in 1832. Her store was operating from the same premises as the magazine by then, but she could not manage both any longer.

She passed away, attended by her loving family, on June 13, 1835.

Read More

Ancestry.com

La Belle Assemblée. London. J. Bell

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann