A humble milliner in 1806, Mrs. Bean rose to giddy heights in just a decade, building a clientele of blue-bloods. In 1816, working with another leading modiste, Mrs. Triaud, she created twenty-six dresses and pelisses for Princess Charlotte’s wedding trousseau, some of which still survive today in museums.

Mrs. Charlotte Bean nee Kennedy (ca.1785-1868)

approx. 1806-08: Bean’s Millinary Rooms 42 Oxford St.

approx. 1809-18: Mrs Bean’s Magazin des Modes 32 Albemarle St.

Born Charlotte Kennedy, the daughter of haberdasher John Kennedy, Mrs. Bean was married very young to her husband Thomas in 1803, and almost certainly acquired an interest in fashion by working for her father. The couple had two children. Son Richard Lewis Bean was born on 18 December,1817. He would become a doctor. Their other son Samuel was born a year later and I have found little about him.

Born Charlotte Kennedy, the daughter of haberdasher John Kennedy, Mrs. Bean was married very young to her husband Thomas in 1803, and almost certainly acquired an interest in fashion by working for her father. The couple had two children. Son Richard Lewis Bean was born on 18 December,1817. He would become a doctor. Their other son Samuel was born a year later and I have found little about him.

Mrs. Bean went into business for herself as a milliner in 1807, launching Bean’s Nouvelle Mode, a magazine of head dress styles, to boost her profile. Despite her aim to make this a monthly publication, it’s not known if she got beyond one issue. I have not been able to track down any copies.

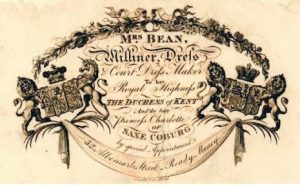

Over the next several years, Mrs. Bean expanded her business to include dressmaking, and rose to become a court dressmaker, advertising her royal patronage on her trade card. With increasing demand, she took on apprentices, one of whom – Elizabeth Lane – put Mrs. Bean on the map for reasons she could not have imagined.

Body Snatchers

At barely 18 years, Elizabeth Lane died of measles in June 1810 and was buried on 21st of that month at St. George’s parish, Hanover Square. Shortly after her funeral, the mourning party, which included Mrs. Bean and her husband Thomas, heard so-called “resurrection men” were in the process of stealing Elizabeth’s body from the grave. They rushed back to the churchyard and Mr. Bean confronted the grave-digger William Webb. They discovered her coffin smashed and her body horribly damaged by shovels and stuffed in a sack just below the ground, ready to be carried off under cover of darkness. Webb, an old man who was variously pitied and excoriated in lurid newspaper accounts, was found to be in cahoots with the body snatchers and was pronounced guilty of the crime at Westminster Sessions on July 13, 1810. He was sentenced to three months in prison.

Mrs. Bean’s Sensibility

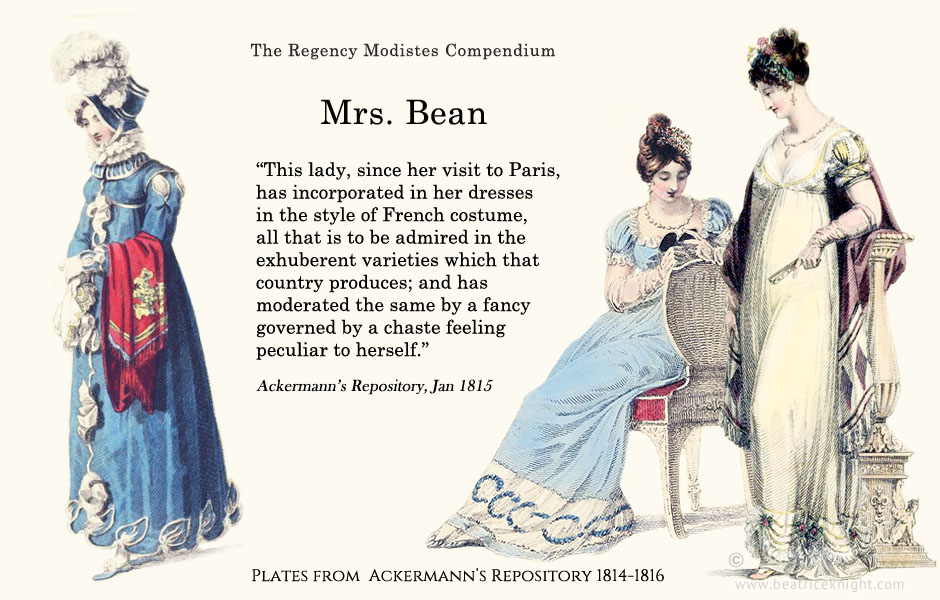

Mrs. Bean’s designs epitomized easy-to-wear luxury, and captured the Romantic sensibility of English fashion during the war with Napoleon. She specialized in court and evening dresses, working with sumptuous fabrics and laces at a time when the war with France constrained supplies. Her detailing was exquisite, with many of her designs requiring hundreds of hours from a team of needlewomen and seamstresses. Real-life examples of her work survive to this day in the Museum of London collection.

Courtesy: Royal Collection

Among the gowns she made for Princess Charlotte’s trousseau, it is likely that Mrs. Bean created one described as a “Prussian blue and white striped satin dress, with a beautiful garniture; above which is a rich broad blond lace, tastefully looped up in the form of shells.” Looped trim positioned above the hem was one of her signature styles, and not associated with Mrs. Triaud, the other modiste working on the trousseau. This striped dress appears to be the one the princess is wearing in the informal portrait (left).

Although Mrs. Bean had been a sought after modiste for a decade when she received the trousseau order, she did not promote her gowns in the popular fashion magazines – dressmakers for the royal family usually kept a low profile. That changed, however when she hit a financial hiccup. Through all of 1814 and Jan-March 1815, virtually every plate in Ackermann’s Repository (April 1814 being the exception) featured her designs, providing insights into her style.

Financial Affairs

Like so many modistes, Mrs. Bean had financial troubles. During the war with Napoleon, her beau monde clientele still expected luxury French fabrics and laces. These had to be smuggled in and cost a fortune. Something had to give and for Mrs. Bean, her English linen draper took the hit. By 1812, she owed him a massive £3ooo (roughly equivalent to $200,000 today). At this man’s insolvency hearing at the King’s Bench hearing in September, 1812, Mrs Bean was described as “a fugitive bankrupt for many years.”

He won a discharge, and she seemed to dodge a bullet as a result. She stepped up her publicity and while Napoleon was in captivity in 1814, she was one of the first English modistes to rush across to Paris to see what Frenchwomen were wearing and to load up on goods impossible to obtain in London for the past decade. She was probably accompanied by her husband’s brother, Richard Bean, an artist and musician, who stayed in France until mid 1815. He then lived with the Beans in Albemarle Street until late in 1817, when he tragically died in a boating accident.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Bean had landed the commission of a lifetime, to contribute a collection of dresses to the vast wedding trousseau for Princess Charlotte, the heir to the throne. With the nuptials looming in May 1816 and the dresses shrouded in secrecy, Mrs. Bean discreetly hired extra help and turned out 26 spectacular gowns and pelisses, among them:

“A very rich evening primrose satin dress with a deep flounce of blond lace of a very beautiful tulip pattern, above which is a broad embroidery of pearls in grapes and vine leaves; the top and sleeves ornamented with pearls to correspond.” (possibly the dress – left – which was worn by the princess)

“A train dress of net, richly embroidered with a beautiful border of roses and buds a quarter and a half deep round the train, the embroidery coming up to meet the waist; body and sleeves richly worked to correspond; the whole dress lined with rich white satin.”

While Mrs. Triaud of Bolton St. made the lavish “cloth-of-silver” wedding gown, along with numerous others, the trousseau order must have restored Mrs. Bean’s finances as well as cementing her place among the superstar modistes of the Regency. Perhaps she retired to enjoy life with her family. She seemed to vanish from the fashion scene after 1818.

Based on ancestry.com research, it appears she died in March 1868, in her eighties.

Read More

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann.