Fashion has always been a copy-cat industry. One of the best known Regency modistes, Miss Macdonald (later Mrs. Smith) was ahead of the curve, creating designs and trim techniques that “inspired” many of her competitors, and promoting the white wedding dress as a style in its own lane.

Miss Euphemia Macdonald (1793-1857)

1810-18: 84 Wells St.

1818-20: 50 South Molton St. Hanover Square

1820-21: 29 Great Russell St., Bedford Square /15 Old Burlington St.

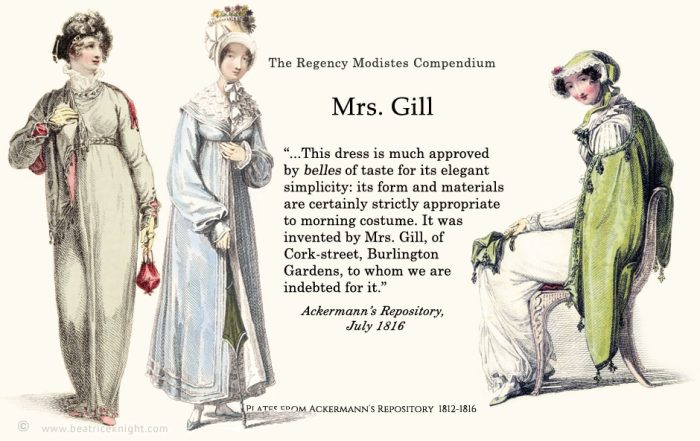

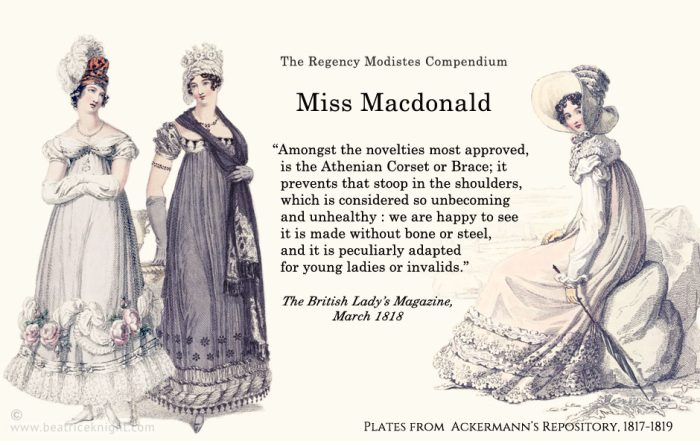

Miss Macdonald was a prominent Regency milliner/dressmaker who left a lasting legacy in her approach to bridal fashion. At a time when wedding dresses were expected to do double-duty as ball gowns, she firmly placed the white wedding dress in its own fashion category. At the time, upscale Regency brides favored lavish gowns of silver and gold, but the white wedding dress was steadily gaining traction and in 1816, Ackermann’s broke the ice by featuring one by her competitor, Mrs. Gill.

Miss Macdonald was a prominent Regency milliner/dressmaker who left a lasting legacy in her approach to bridal fashion. At a time when wedding dresses were expected to do double-duty as ball gowns, she firmly placed the white wedding dress in its own fashion category. At the time, upscale Regency brides favored lavish gowns of silver and gold, but the white wedding dress was steadily gaining traction and in 1816, Ackermann’s broke the ice by featuring one by her competitor, Mrs. Gill.

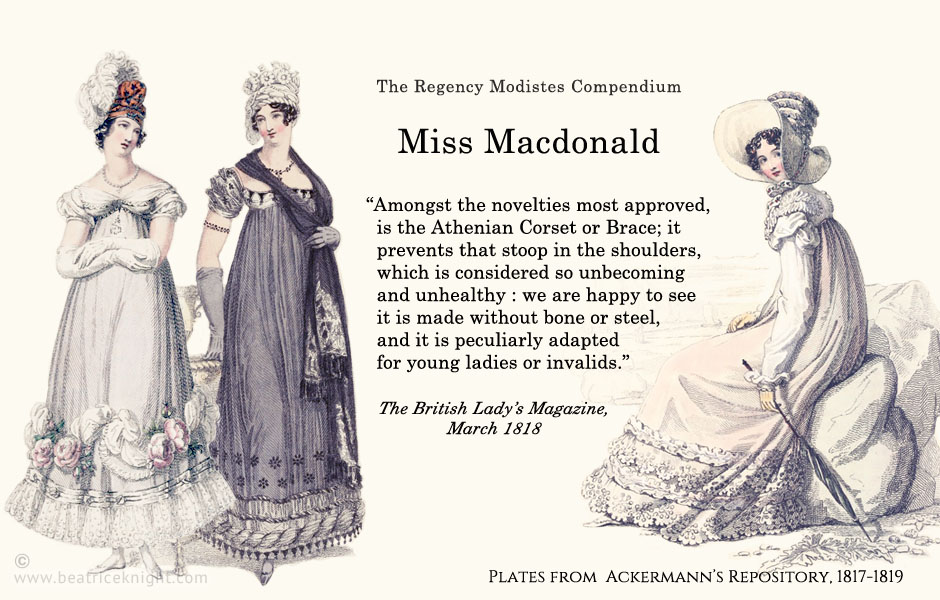

By then Miss Macdonald had been making white wedding dresses for five years, some of which appeared in fashion plates as “full dress.” Finally, she promoted a gown (left) in the March 1818 Ackermann’s spread, which was arguably the most distinctively and exclusively bridal of those first seen in Regency fashion plates. The others published in 1816-1818, featured gowns by Mrs. Gill and Mrs. Bell which were virtually indistinguishable from ball dresses.

Miss Macdonald had started her dress-making career as an overworked, underpaid “improver” in her teens, until finally she established her own modiste shop in Wells Street in 1810. After building her business, making quality attire for upper middle-class and genteel clientele, her signature styling attracted the attention of a lady of high rank. She was commissioned by that noblewoman to create a court dress for the 1817 Season. Knowing she would never get a better chance to make her name as a top tier modiste, Miss Macdonald decided it was time to “rebrand” herself and invest in classier shop premises.

In the midst of orchestrating her move, another opportunity presented itself with the tragic death of Princess Charlotte in November 1817. Miss Macdonald rushed to create several high-end mourning gowns aimed at the beau monde. One of these, a carriage costume (left) was featured in Ackermann’s Repository, January 1818.

In February of that year, just in time for the new Season, Miss Macdonald shifted her stock and staff from Wells Street to an elegant Mayfair building in South Molton Street. She then launched a major promotion, paying to have her designs featured in Ackermann’s Repository and the British Lady’s Magazine for the entire of 1818. As part of rebranding she made a splash in the March issue of the latter, showcasing five of her designs in a collection which included the court dress (below), along with opera, ball and morning gowns, and various headwear.

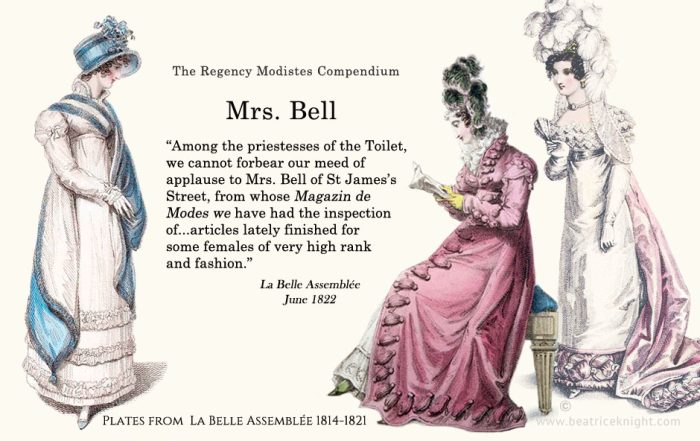

Observing the example of her competitor Mrs. Bell, who made a profitable line of women’s corsetry, she “invented” the so-called “Athenian corset” and promoted this heavily.

Despite her efforts and investment, Miss Macdonald’s business expansion was complicated by her personal life. She married William Smith in June 1818 and faced the dilemma of a name change in the middle of her biggest advertising campaign. She delayed making the switch until January 1819, in most magazines, but started using Mrs. Smith in a few plates from September 1818 onward. The couple welcomed their first child in November 1820. She also faced stiff competition, and not just from other modistes who had profited from the fashion frenzy surrounding the wedding of Princess Charlotte of Wales to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg in May 1816.

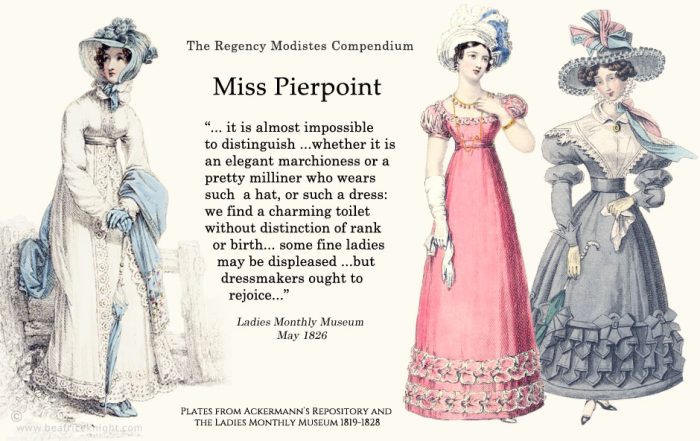

Like most in her business, she was losing middle-class clients to warehouses whose ready-to-wear collections were better and cheaper than ever before. Probably struggling to juggle new motherhood with running a business, she handed her shop over to one of her senior staff, Miss Caurette early in 1821. That young lady struggled to hold her own against emerging names like Miss Pierpoint of Henrietta St. On August 6, 1822, an advertisement appeared in the Morning Post, showing Miss Caurette accepting lady’s maid applications at her shop. This was a side hustle for milliners and dressmakers who needed to make extra pennies, and it’s a safe bet that those who advertised such services were usually not making dresses for the ton. By 1823 the South Molton Street shop was out of business.

In the meantime Miss Macdonald had removed herself to Great Russell Street, Bedford Square, where she continued making dresses and hats until the end of 1821. At the same time, she had taken a premises at Old Burlington St. on a short term lease taken over by a dentist late in 1821. She continued to promote herself Ackermann’s Repository until May of that year, but Miss Pierpoint took over the monthly fashion plate promotions from June onward. She would co own to ‘own’ the 1820s, outpacing even Mrs. Bell for prominance.

Miss Macdonald’s Fashion Sensibility

Miss Macdonald’s design sensibility was fashion forward through most of the years in which she served a predominately middle-class clientele. Her designs convey personal tastes more aligned with Paris than London, at a time when a decade of war and decoupled English fashions from French. Modistes like Mrs. Bell, and Miss Pierpoint clearly drew inspiration from her for gowns they made in 1819/20 – some seem to be transparent knock-offs of styles, detailing and trims that Miss Macdonald created years earlier.

In 1820, British fashion was entering its biggest transition since 1800, but Miss Macdonald was poised to go out of business. The soft, neo-classical lines and Empire silhouette of the past two decades were about to be consigned to history. Waists would plummet, bodices would tighten and the the Romantic era silhouette would consolidate, with a more natural waistline, puffed sleeves, and ever-widening skirts.

The 1820s would be Miss Pierpoint’s decade. Drawing inspiration from Miss Macdonald’s designs, she would create a signature look at the cutting edge of the dramatic changes. However, there were more sweeping changes underway than simply design trends. As the 1820s rolled on, the modistes of London were under siege by a new breed of fashion warehouses – early incarnations of department stores – which beefed up their ready-to-wear options and offered inexpensive made-to-order and alteration services. Why pay a fortune for a snooty modiste to look down her nose at you, when you could dress like a queen – and get treated like one – for half the cost?

The middle class, who had previously kept countless dressmakers afloat, increasingly looked to these grand new stores. And the women who were once self-employed as their dressmakers, found themselves employed to do piece work and alterations for abysmal wages. On the one hand, middle class prosperity had expanded the market for high-end clothing; on the the other hand, competition for that market was rapidly exploding.

These socio-economic currents placed modistes in a difficult position. While Miss Pierpoint found a way to weather the 1820s by making her brand exclusive and marketing aggressively to fashionables who would never be seen in the same outfit worn by some merchant’s wife. Miss Macdonald opted for family life, it seems, ending her fashion career after becoming a mother.

Her fate…

Like so many women in business during the Regency era, Miss Macdonald simply vanished from the public record. In an effort to trace her, I searched Post Office directories and newspapers, marriage banns, death notices, parish records, and fashion publications. Eventually, I discovered that she had married in mid-1818 and became Mrs. Smith of Old Burlington St. She began a name change transition in September 1818 among the multiple magazines that featured her garments. In 1819, she completed the change with her fashion plates listed under “Smith” in Ackermann’s Repository. She appeared to have difficulty juggling domestic life and business after starting her family, and closed her business in 1822. She died in 1857.

Learn More About Regency Modistes

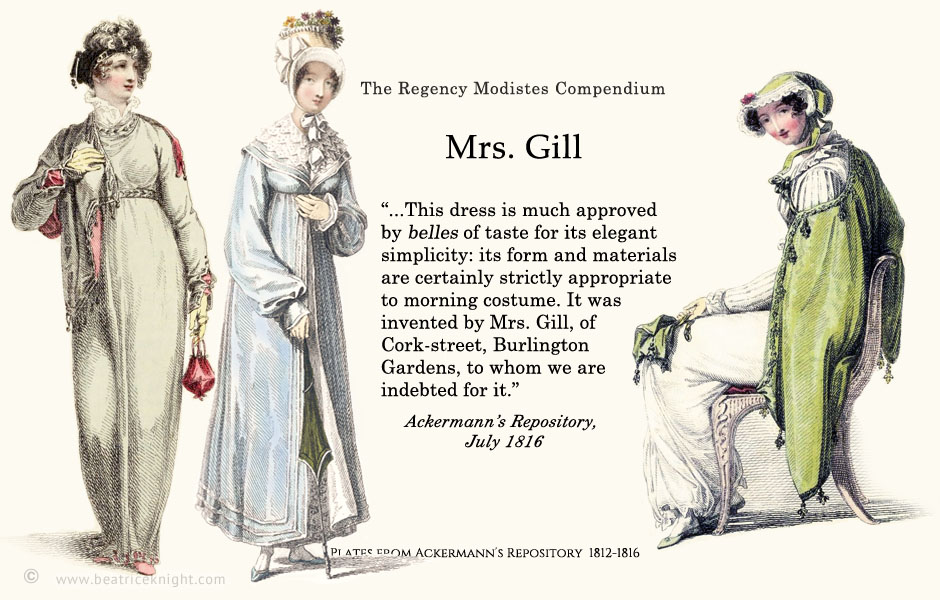

Mrs. Gill

Mrs. Gill was one of the leading modistes of the Regency, and pioneered the design of white wedding dresses at a time when few women of fashion wore them. She was also deeply involved [...]

Miss Macdonald

Fashion has always been a copy-cat industry. One of the best known Regency modistes, Miss Macdonald (later Mrs. Smith) was ahead of the curve, creating designs and trim techniques that "inspired" many of her [...]

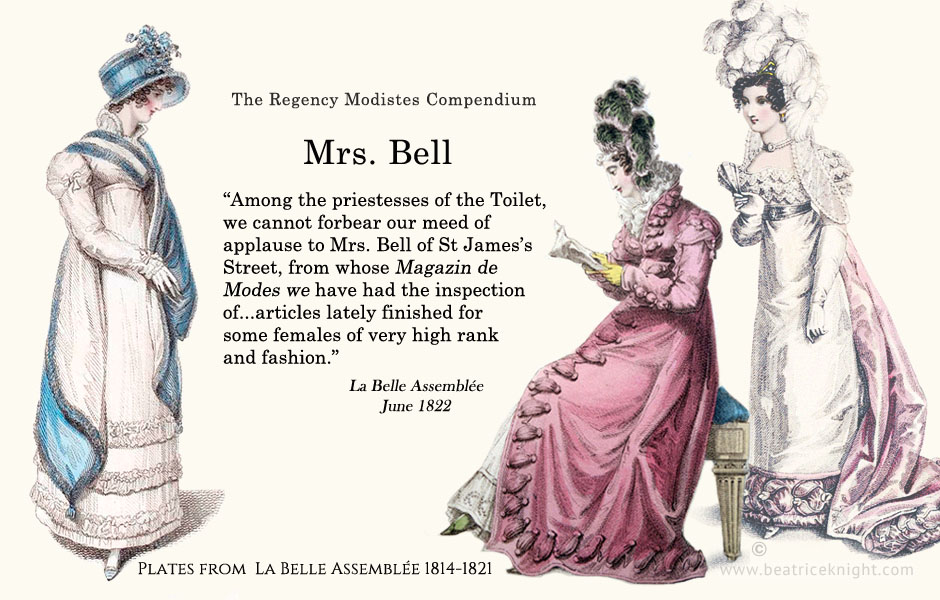

Mrs. Bell

Fond of declaring herself the inventress of this or that fashion, Mrs. Mary Ann Bell was not above purloining designs from other magazines and calling them her own. She was the great survivor of [...]

Miss Pierpoint

The self-declared "inventor of the Corset à la Greque," Miss Pierpoint was the busiest marketer of all the Regency modistes, with over 230 of her dresses appearing in fashion plates across multiple publications from [...]

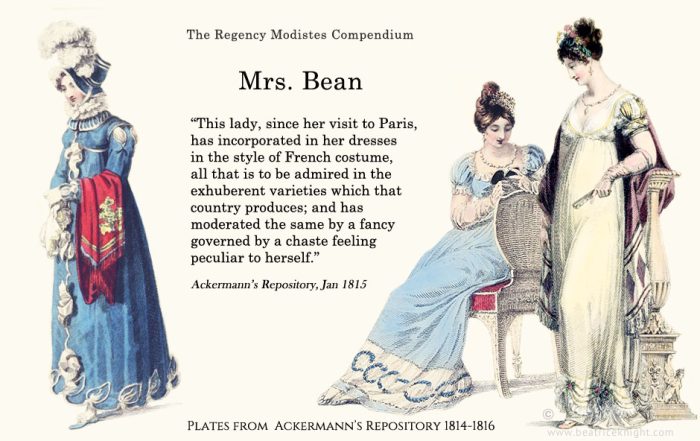

Mrs. Bean

A humble milliner in 1806, Mrs. Bean rose to giddy heights in just a decade, building a clientele of blue-bloods. In 1816, working with another leading modiste, Mrs. Triaud, she created twenty-six dresses and [...]

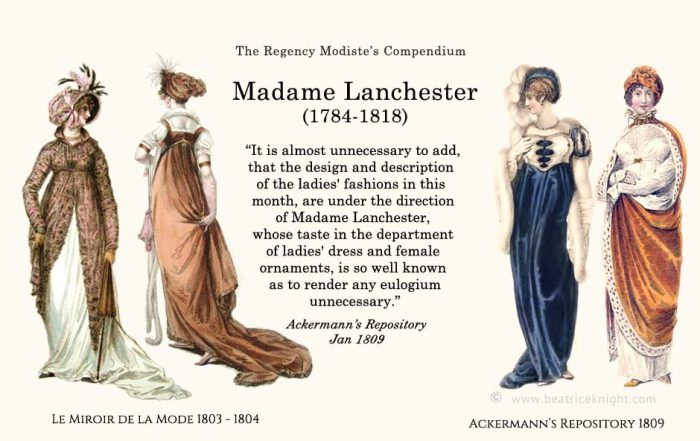

Madame Lanchester

By the time Regency modiste, Madame Lanchester was jailed for bankruptcy in Marshalsea Prison on February 8, 1812, she had spent more than a decade as one of London's best known milliner/dressmakers. Unfortunately, her [...]

Read More

The British Lady’s Magazine, 1817–

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann.

The Morning Post, London.