A List of Dressmakers in Regency London

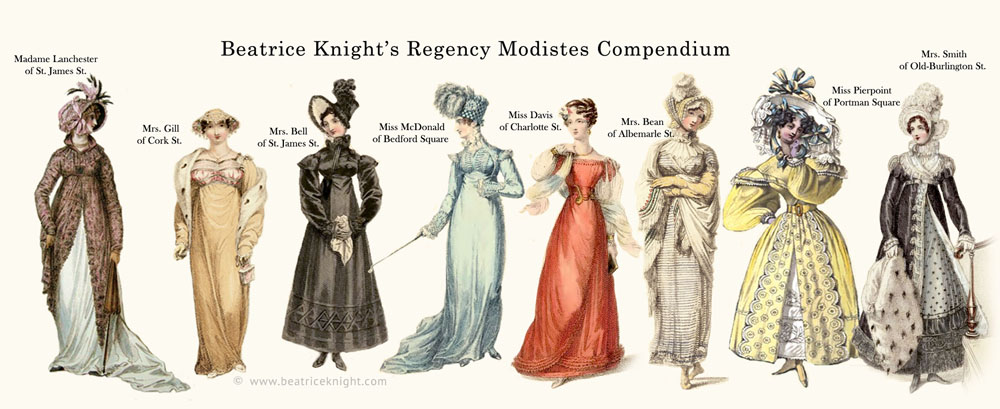

This post lists some of the 160 women included in my Regency Modistes’ Compendium (due for release December 2023). The Compendium represents the first and only comprehensive research into the identities and lives of the forgotten women who defined Regency fashion from 1800 to 1830. Variously known as as milliners, modistes, mantua makers, marchands des modes, and dressmakers, these women built the foundations of the present-day design fashion industry, as I discovered when I began my deep dive into their stories early in 2018. I’ve been adding to this post since it was first published in 2020. I’ll leave it here as a free resource after my book is available.

The garment industry was one of the few self-employment opportunities open to early nineteenth century women of all classes. Official records (Children’s Employment Commission, 1842) estimate that at least 1000 milliner / dressmaker businesses operated in Regency London. Countless women made a living–occasionally an excellent one–creating fashions for well heeled Regency women. In general, they learned dress-making as apprentices, also known as “improvers,” working for a modiste with her own business. Most continued working for wages. A few struck out on their own. Those with a steady clientele could expect to earn at least twice the wage of a lady’s maid. Sewing was also one of a handful of self-employment opportunities available to women of any social class. Among the most popular locations for dress shops was Albemarle St., while specialist hat-makers gravitated to Cranbourne St. (The term “milliner” did not become specific to hat-making until later in the 19th century.)

These early fashion entrepreneurs are not easy to track down. This list is restricted to self-employed women who ran their own business of which at least half was dedicated to garment-making and who also operated shops/showrooms open to the public during trading hours. With a few exceptions, female-owned businesses in the early 19th Century were not listed in directories such as the Post Office, Kent’s, Wakefield’s, Pigot & Co, Robson etc. The names on this list are have been verified in Regency era sources including: newspapers and fashion magazines, court proceedings, ancestry.com, trade directories, and the usual library bibliographies. Verifying exact dates of business operation is next to impossible – if a date is given on an entry, it means I verified it in a print source.

CITATIONS: For ease of lay-out and reading, I did not clutter this post with footnotes and citations. My book, The Regency Modistes’ Compendium provides sources in full, if needed for academic research. If you wish to quote from this blog, please accredit and link appropriately. If you have questions or can add helpful details about any of the women included, feel free to reach out!

Six Regency modistes are women whose designs were promoted in multiple fashion plates, extending their reach and influence. These women are profiled in depth, in separate blog posts.

Misses Allen: 1790s-1808 – 90 Pall Mall

The Miss Allens were in business from the late 1790s until they hit financial troubles in 1802. In December of that year, they auctioned off their stock and household furnishings and in January 1803, Frances Allen placed a notice in the London Times that she had assigned all her estate and effects to trustees for the benefit of their creditors. The sisters resumed business some time after this, but struggled again and Frances Allen was paying dividends to creditors once more in 1808 (Morning Chronicle, July 20, 1808).

Mrs. Allen: 1818-18?? – 20 Pavement; 3 South Place, Finsbury Square

A milliner and dressmaker to the middle classes, Mrs. Allen moved from Pavement to South Place in March, 1821. She advertised occasionally in newspapers from 1818 onward. It is not clear if or how she was connected to the Miss Allens (above).

Mrs. Barclay: 1807-1834 At: 33 Frith St., Soho; 16 Charles St. Cavendish Square(1815); 44 St. James St. (1816); 51 Piccadilly (Nov.1819); 29 Regent St. Pall Mall (1820); 23 Duke St. (1824); 1 Lower Brook St.(1830); 24 Somerset St.

There was never a dull moment for a Regency modiste. Like many in her trade, Mrs. Barclay found herself in court in 1823, but not for financial reasons. She had been involved in an ugly scene at the Haymarket Theatre on Oct. 11, 1822 when a nuisance patron had to be removed and assaulted theater staff. At the trial in January, 1823, she was called as a respectable witness only to find herself threatened with assault, leaving both her husband and the prosecutor to respond by challenging the defendant to a duel. Eventually the matter was settled, leaving her with dinner conversation for the rest of her days.

Long before those events, Mrs. Barclay had set up shop as a milliner dressmaker specializing in ready-to-wear evening attire at competitive prices, and boasting dresses made to order within hours. She was a prolific newspaper advertiser and a pragmatist who steered her business toward the profitable corsetry niche. Her lengthy and turbulent career is explored in detail in the Regency Modistes’ Compendium (forthcoming Dec. 2023).

Misses Mary and Harriet Baxter : 1828-1830 – Tottenham Court Rd.

Seamstress milliners, the two sisters catered to a mostly middle class clientele. They dissolved their partnership in July 1830 because of debt.

Mrs Charlotte Bean : 1807-1826 – 42 Oxford St., 32 Albemarle St.

Mrs. Bean, one of the more notable modistes of the era had a long career. The 1822 Pigot & Co directory lists her still in business at Albemarle St. Read more…

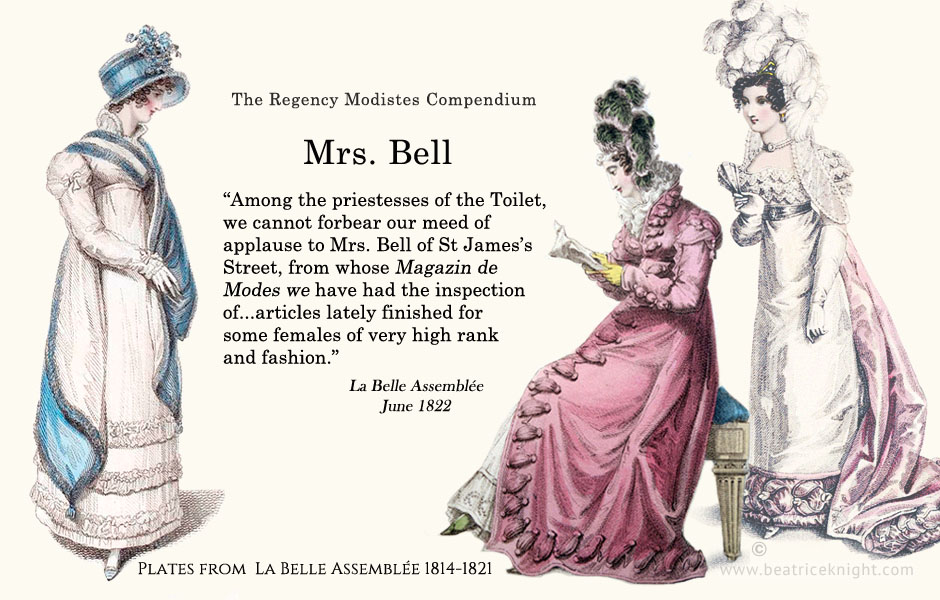

Mrs. Mary Ann Bell : 1810-1835 – 22 Upper King St., 26 Charlotte St., 52 St. James St., 3 Cleveland Row

What Mrs. Bell arguably lacked in originality and flair, she made up for with self-promotion. No modiste received more press, and fortunately for Mrs. Bell, she did not have to purchase most of her promotion. Marrying into the Bell family, owners of fashion bibles such as La Belle Assemblée and, from 1824 onward, the World of Fashion, was good for business. It is thought that Mrs. Bell wrote all or most of the copy for the fashion columns that accompanied her designs. Read more…

Miss Berry: 1800-1805 At: 155 New Bond St.

Milliner dressmaker Miss Berry took over her shop in New Bond Street from a well-known milliner, Miss H. Bang, who had moved there from Bury St. some years earlier (London Times. Oct 17, 1795). Miss Berry inherited the impressive clientele and became a milliner to the Duchess of York. In 1801 and 1802, her ‘pilgrim hat’ was a craze, featured in newspapers and magazines.

Mademoiselle Binet : 1793-?? – 34 Golden Square

Mlle. Binet arrived in London with an influx of French refugees soon after the “September Massacres” of 1792 warned of things to come as the Revolution moved from semantics to slaughter. She made hats and gowns, including court dresses.

Mrs. Bingley : 1805-1814- 91 New Bond St.

Mrs. Bingley’s business was taken over by her senior seamstress / manager Mrs. Etches after her death.

Mrs. Sarah Bird : 1811-?? – Great Charles St.

Mrs. Bird was a dressmaker who worked on a small scale within her community. Referenced: London and Country Directory , 1811

Half-mourning evening gown by Miss Blacklin. La Belle Assemblée, November 1810.

Miss Blacklin: 1805-1815 – 11 Blenheim St, Bond St

Miss Blacklin was a successful milliner and dressmaker who run a substantial business, making to order as well as selling ready-to-wear. She was an advertiser in La Belle Assemblée through its early years from 1806-08. A half-mourning evening dress of hers (left) was featured in November 1810, and another evening gown in March, 1811.

Mrs. Blackburn: 1819-1825 – 141 Jermyn St. St James

Mrs. Blackburn set up shop as a dressmaker and milliner after her husband James, late of the Royal Navy drowned in 1819. Obliged to support herself she fell victim of an early example of identity theft, when a woman claiming to be a Navy widow called Blackburn was on trial in the Court of King’s Bench in 1822. Finding herself the subject of undeserved speculation, and fearing her business would suffer, Mrs. Blackburn felt compelled to notify her clients and acquaintances that she was not the woman facing criminal charges.

Mrs. Bruce : 1795-180? –

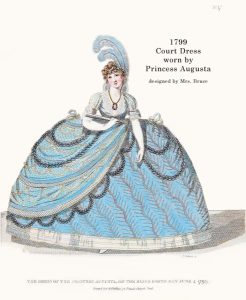

Court dress of Princess Augusta, worn on the King’s Birthday, 4 June, 1799. Richard Phillips, The Fashions of London and Paris, July 1799. Plate restored and recolored by Beatrice Knight.

Dressmaker to Queen Charlotte and the royal household, Mrs. Bruce had a small clientele numbering women of the highest rank. She made matching mother-and-daughter court dresses in for the King’s Birthday in 1799 (right) which were featured by Richard Phillips in his Fashions of London and Paris, .

Mrs. Sophia Buzzio : 1810-181? – Charles St.. Grosvenor Square

On 9th January 1811, milliner/dressmaker Mrs. Buzzio appeared in the Old Bailey prosecuting a servant, Mary Casey for theft. Mary was sentenced to a year in prison and a fine of one shilling.

Miss Caurette: 1822-1825 At: 50 South Molton St., Hanover Square

Dressmaker Miss Caurette, a Frenchwoman, set up her business, after a tea merchant’s brief occupancy in the same premises occupied by Miss Macdonald, later Mrs. Smith. Miss Caurette was probably trained by Miss Macdonald, but she did not advertise herself as a successor. She ran a modest business, also accepting advertising for ladies’ maids and companion positions. She was listed in Pigot, 1825-26, and was still handling ads for domestic staff at that time. She closed her business not long after, and the premises was occupied by a merchant.

Mrs. Christian: 1799-18?? – 22 Conduit St., Hanover Square

Mrs. Christian opened her mantua making business from her home in February 1799. She provided dresses, millinery, and fancy dress costuming.

Bill-head Mrs. M. Clark (c. 1805) © Trustees of The British Museum

Mrs. Mary Clark: 1800-1825. At: 56 St. James St.; 35 Great Russell St., Bloomsbury

Mrs. Clark was a well-known court dressmaker and modiste in the early- to mid-Regency period. She advertised in the newspapers, La Belle Assemblée (1807) and Le Beau Monde (1808), and was listed in Holden’s, 1811. She ran a good business until 1818, when she went blind from doing close needlework. Taking an assistant with her, she retired to Gravesend, where she continued sewing by touch.

In April 1825, she suffered serious burns when her clothing caught fire. Her assistant, trying desperately to help, also caught fire and the two women were rescued by a pair of yard boys in Mr. Clark’s employ. The women’s burns were treated, and they recovered, but Mrs. Clark was left in failing health and never returned to sewing.

Madame Louise Clarot: 1818-1826 At: 39 Albemarle St.

Advertising her establishment as Madame Louise’s, this milliner dressmaker also rented out a four-room apartment near St. James to members of parliament and gentlemen wanting rooms for extended visits. Listed in Pigot 1822 and 1825-6, she was an upper tier modiste whose showroom was frequented by many movers and shakers of the day, who may also have visited Mrs. Bean’s establishment a few doors away.

Miss Letitia Collins : 1806-1811 – 155 New Bond St., 20 Lower Grosvenor St., 37 Half Moon St.

Miss Letitia Collins : 1806-1811 – 155 New Bond St., 20 Lower Grosvenor St., 37 Half Moon St.

As a milliner, and court and fancy dressmaker to the Princess of Wales and the Duchess of York, Miss Collins ran a sizable establishment, with a team of staff including a milliner who trimmed and fitted ladies hats to order, a senior dressmaker, an “improver” and an apprentice. Miss Collins moved from New Bond St to Lower Grosvenor Street in February 1807, holding a sale of her stock ostensibly to make her removal easier. She moved again in October, 1808 to Half Moon St. in the midst of financial troubles and traded at that address for the next year, trying to clear debt. In 1809, she advertised (Morning Chronicle. 24 March) a half price sale “in consequence of a Partner coming into the Establishment.” She promoted a carriage costume in a plate (left) in Ackermann’s Repository in January 1810, but her design was credited to Miss Millman (possibly the ‘Partner’), which probably didn’t help her stress levels. March, 1810 saw her in bankruptcy proceedings and on 27 April, 1810 a bankruptcy auction of her entire stock-in-trade was conducted on the premises, along with a wine tasting. Miss Collins continued her efforts to repay debt until early in 1811, but was unable to resume her business.

Mrs. Cookney : 1800-18? – Sackville St.

A milliner dressmaker, Mrs. Cookney became a supplier to the Duchess of York in January, 1801, and promoted a large collection of lambs wool hats in Bell’s Weekly Messenger that month.

Mrs. Cooper : 1825– – 21 Western Exchange

A dressmaker, milliner, Mrs. Cook also sold a few powders and potions at her shop including Ispahan Powder for darkening red or grey hair.

Mrs. Crombie : 1824 – 182? – 57 Tavistock St.

A dressmaker with a mostly middle class clientele, Mrs. Crombie made her shop available for notices and interviews. In December 1824 through mid-January 1825, the headmistress of a Southampton girls’ boarding school interviewed admission candidates for her school at the shop. Mrs Crombie also accepted applications for lady’s maid and genteel employment on behalf of clients.

Mrs. C Crosby (formerly Miss Carbery) : 1824 – 182? – 3 George St. Hanover Square

Predominately a milliner, for an upscale clientele, Mrs. Crosby advertised her return from Paris in 1825, with an abundance of new plumes and ornaments for the Season. She was perhaps the only miller in London to operate a Ladies Only baths at her establishment. Having seen such facilities in Paris, she offered her clientele “A Bath served at any hour on a minute’s notice.”

Mademoiselle Aimee Danet : 1823-182? – 227 Regent St

After eight years working her way from apprentice to head milliner at Mademoiselle Laure Hardy’s, Aimee Danet went into business for herself in November 1823. Over the following year she advertised her fashion choices at “very moderate prices.” No record seems to exist of her success or failure.

Regency evening dress. By Miss Davis. Retinted by Beatrice Knight.

Miss Davis : 1825-182? – Charlotte St. Bloomsbury

Miss Davis’s designs (left) were featured in Ackermann’s Dec. 1825 and each month from January to May of 1826.

Madame De Rozier : New Bond St.

Operated by Miss Frances Antoinette, the business ran into financial troubles in 1798, and filed for bankruptcy. Miss Antoinette worked to pay off her creditors through 1799, but could not save her business.

Madame Devy : 1827-183? – Grafton St., Bond St., 73 Lower Grosvenor St.

Appointed milliner and dressmaker to the Queen in September 1830.

Madame Duchon: 1820-1833 At: 34 Conduit St.; 158 New Bond St.

Listed in Pigot, 1822 and 1825-6, Madame Duchon was one of London’s leading dressmaker milliners during the “big hat era” of the late Regency. She advertised her move from Conduit St, to New Bond St. in the Morning Chronicle. May 6, 1824. On 28 April, 1829 (Morning Post), she advertised her move from Conduit St. to New Bond St. In the Queen’s Birthday celebrations in February 1833, Madame Duchon’s illuminated window was mentioned in the Evening Post. She was milliner to the Queen by then.

Miss Dulhunty : 84 Wells St., 7 Princes St (1813)

Miss Dulhunty was at Wells St. just before Miss Macdonald took over the shop premises there.

Mrs. Duval : 18?? – Bond St. Mayfair

Madame Duthe: 1810-1816 – 35 Albemarle St.

Mrs. Etches : 1815- – 91 New Bond St

Mrs. Etches took over the business previously run by the late Mrs. Bingley. She had designs featured in The British Lady’s Magazine in 1815. In August of that year she promoted a new stay she “invented” – getting very short and the bosom needed extra support, so many modistes were jumping on that bandwagon.

Mrs. Fisher : 1800 – 18?? Bond St; 6 Melina Place, Westminster Rd.

In January, 1803 Mrs. Fisher moved from Bond St. where she had worked as a seamstress, to Melina Place to offer a wider range of dress and corsetry-making. It’s not clear how long she lasted.

Mrs. Fiske : 1804 – 1812? 81 New Bond St

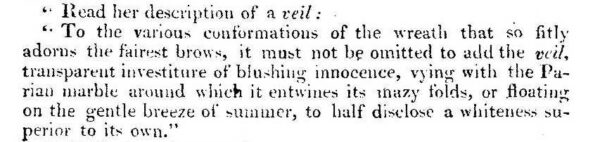

Mrs. Fiske was a big name in her time, patronized by royalty and nobility. She advertised in La Belle Assemblée in 1807 and ran a mail-order service to the East and West Indies, providing bespoke fashions to ladies in colonial outposts. Her lasting legacy was in publishing. In 1806 Richard Phillips Fashions of London and Paris changed its title to Records of Fashion and Court Elegance and was published from 1807-1809 under Mrs. Fiske’s direction at a hefty 50 shillings per volume. It featured 47 plates of her designs, with her extravagant editorial (which seemed to inspire Mrs. Bell’s style when she took over as editorial director of La Belle Assemblée.) She was such a household name that the Edinburgh Review singled her out for a lengthy, and very funny, satirical essay mocking her gushy tributes to her royal patrons and flowery descriptions of various fashions, which was extensively quoted in both the Monthly Mirror (October, 1808) and Anti Jacobin Review (November, 1808) .

Anti Jacobin Review. Nov, 1808.

Madame Armandine Follet: 1829-1860 At: 49 Conduit St. see also Madame Chopard

Having succeeded the original Marthe Chopard, who died in 1825, the new Madame Chopard (Armandine Adelaide Legros) married Pierre Follet (Marthe’s widower) in Paris on February 4, 1826.

The story of this famed fashion house is discussed in detail in the Regency Modistes Compendium (due for release Dec 2023).

Mrs. Franklin: 1805 – 1813 – Piccadilly

Mrs. Franklin was known as a quality dressmaker with a mostly upper middle-class clientele. Her business was taken over in 1813 by Miss Powell. The change-of-hands was referenced in La Belle Assemblée (Dec, 1813).

Mrs. Franks: 1795-18?? – St. James St.

Mrs. Franks, a leading milliner modiste for fashionable women in the mid-to-late 1790s, was appointed to supply dresses to the Princess of Wales (notice gazetted in the Morning Post 1 August, 1798).

Miss Friend: 1811 – 18?? – 82 St. Albans St

Miss Friend was a dressmaker for a small middle-class clientele. She was referenced in the London and Country Directory , 1811.

Miss Gardener: 1822 – 41 New Bond St

Miss Gardener advertised opening her new business in Jan 1822. (London St James Chronicle and Evening Post. Jan 31, 1822) Stating in her advertisement that she had “lived at some of the first houses in town,” it seems she had been a seamstress for some other modiste of note before striking out on her own. After she went out of business, her premises was taken over by Miss Place, another milliner/dressmaker who catered to a respectable middle class clientele. Both women made a little extra money handling advertisements for ladies’ maids, governesses etc.

Mrs. George: 1805-1828 At: 48 Park St. Grosvenor Square; 116 Jermyn St.

Milliner and fancy dressmaker to the Princess of Wales, Mrs. George frequently ran the same advertisement for the largest range of gold and silver muslins in London from 1808-09 (see London Morning Post. June 4, 1808). Somewhat unusually for dressmakers patronized by royals, she sold goods for “ready money,” which probably helped her stay afloat when blue-blooded customers were slow to pay. Late in her career, she was in smaller premises and reduced circumstances, and accepted advertising in her shop for people seeking servants.

Mrs. Ghalter : 1775-1806 – Blenheim St.

Milliner/dressmaker to the Queen for some 30 years, Mrs. Ghalter had no need to promote herself. She retired comfortably after a long career.

Misses Giles, Isabella and Mary : 1819?-1824? – 350 Oxford St.

Milliner/dressmakers, the Giles ran a small business catering mostly to middle class clientele. They were listed in the Pigot & Co London business directory, 1822. I have not found them listed in women’s fashion magazines, but they advertised occasionally in newspaper trade listings.

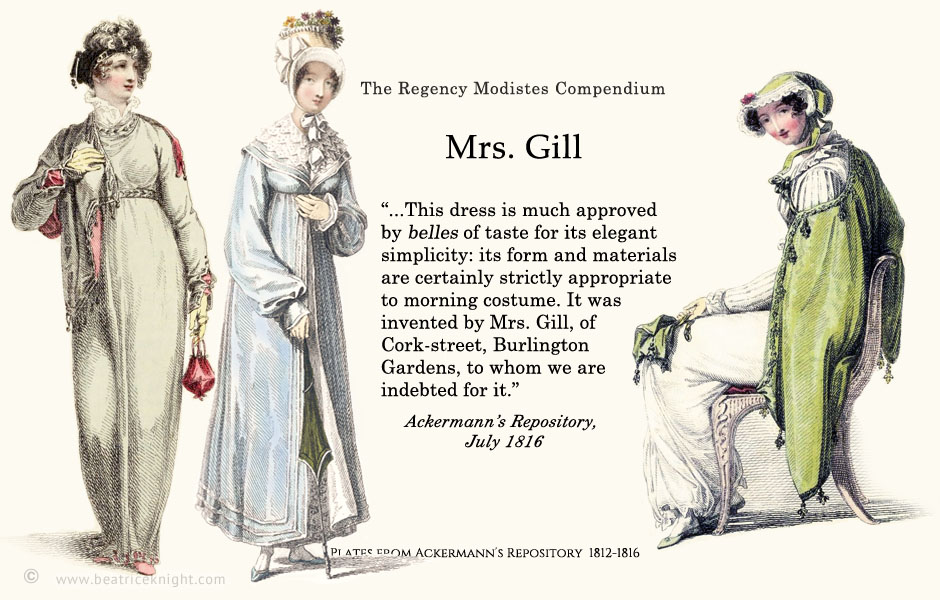

Mrs. Gill : 1807-1820 – Cork St. Burlington Gardens

One of London’s leading modistes during the 1810s, Mrs. Gill’s fashion plates featured in multiple issues of Ackermann’s and other magazines, and with her husband she was involved in philanthropy. Read more…

Mademoiselle C. Giroust: 1824-? At: 91 Wimpole St., Cavendish Square

Formerly of Madame Triand’s establishment, Mademoiselle Giroust advertised the opening of her new Wimpole St. shop, having just returned from Paris (Morning Chronicle April 29, 1824).

Mrs. Gray : 1816-1820s – 34 Park St., Grosvenor Square

Not a leading modiste, Mrs. Gray ran a small dress-making and alterations business, and also accepted replies to advertisements for lady’s maids. Advertisements directing replies to her shop appeared in the Morning Post in 1819, and other years.

London dresses by Mrs. Green. Ladies’ Monthly Museum, June 1813.

Mrs. Green: 1811-1826 At: 398 Oxford St.; 26 Old Bond St., Piccadilly.

Listed in Holden’s Directory (1811), Mrs. Green took over the promotional spot Mrs. Osgood (Madame Lanchester’s successor) did not renew in the Ladies Monthly Museum in 1813. Her designs were featured in that publication from May 1813-March 1814. She was never a leading modiste, but created pleasing, humdrum fashions that targeted the readership of that magazine – ie. the well-dressed middle class and provincial gentry. Nothing to frighten the horses here!

A Morning Post ad on March 26, 1814 saw her offering to collect donations for a distressed family in need. She was still listed in business in Pigot, 1825-26.

Miss Griffin : 1817-182? – 26 Gt Russell St.

The 1822 Pigot & Co London business directory listed her as in business. She is easily confused with Mrs. Griffin of Little Ryder Street, however they are not the same person. I believe Miss Griffin may be the daughter, but I have not yet verified that.

Mrs. Griffin : 1812-1818 – 10 Little Ryder St. St James

Mrs. Griffin was a dressmaker and milliner to the Princess of Wales and the Duchess of York, who targeted her designs at the beau monde. She ran a haberdashery and modiste shop in partnership with her husband, a ‘man-milliner,’ as they were known in those days. In 1813 she created a dress, which became all the rave, for the Vittoria fete at Vauxhall Gardens and in the following year she promoted a Grand Jubilee costume which she advertised in the Morning Post. In April 1814, she displayed an attention-grabbing illumination in her store window of the island of Elba, commemorating Napoleon’s exile there. In 1816, her husband faced bankruptcy proceedings but Mrs. Griffin expanded their business in an effort to dig them out of their hole. She hired several apprentices and improvers in May/June 1816 and a young lady to work in the showroom. She had mixed success, and the couple were still paying down their creditors in 1818 and closed their shop that year.

Miss Laura Hardy : 1815-1826 – 40 Albemarle St.

Mademoiselle / Miss Hardy was a well-known modiste who trained several women who went on to set up their own businesses, among them Miss Danet who was with Hardy for eight years as head milliner until 1823. Her mother (or Miss Hardy herself, using “Mrs” as a dignity) was described as a French lady in colorful reports of a legal dispute she had with a “troublesome” and noisy lodger, one Mr. Walker, in 1822. After she took legal advice, he tried to get the jump on her by claiming she had assaulted him. In court, he produced a diary of their interactions and complained that her servants used foul language, refused to accept his mail, and that after his return from a long walk one evening her cook deliberately sent up a spoiled meal of “beautiful ribs of lamb…at least five minutes overdone...” Mrs. Hardy, “whose appearance and manner are quite those of a gentlewomen” (London News) explained that Mr. Walker made living in her home intolerable by constantly banging a drum and blowing a postman’s whistle. She brought with her to court several gentleman who confirmed her account.

Laura Hardy was listed in the Pigot & Co London business directory, 1822 at her Albemarle St. address. She became Madame Girardot in January 1825, upon marrying. Shortly after, she lost her business ledger book and her husband placed notices in various newspapers over subsequent months, stating that falsified receipts would not be accepted as records of payment.

Miss Heffey : 1806- 18? – Pall Mall

A milliner dressmaker, Miss Heffey’s designs were featured in Le Beau Monde in June 1807.

Mrs. H. Hill : 1803- 18? – 3 Kirby St., Hatton Garden

Mrs. Hill launched her dressmaking / millinery business in January, 1803, promoting herself as making the latest Paris styles at inexpensive prices.

Mrs. Hinchliffe : 1798-1817? – 31 Bedford Row; Charlotte St. Bedford Square

Mrs. Hinchliffe launched a millinery dressmaker business as a young married woman, and almost immediately struck financial problems. After trying to stay afloat, she auctioned off her stock to pay her creditors in March, 1801 and kept herself afloat by dress-making for remaining customers for then next decade, gradually building a good business. She attempted to make a splash of sorts in December 1815, featuring her designs in the British Lady’s Magazine. The promotion did not appear to do anything for her and she appeared to retire a year or so later.

Mrs. Hubert : 1798-180? – 2 Bennet St., St. James

Mrs. Hubert was a milliner and fancy dress maker in a modest way to respectable, mostly middle-class clientele. Hers was a shop where people could pay a few pence to leave notices of employment, for which she accepted replies. Advertisements mentioning her shop as the venue for replies appeared in the London Observer (May 5, 1799) and other daily papers.

Mrs. James : 1809-? – 15 New Bridge St. Blackfriars

Mrs. James had a ‘Bishop’s mantle’ featured in Ackermann’s Repository, May 1809, for which she was credited in the June issue. She also promoted her wide color range of Scotia silk (a cotton and silk blend) for pelisses and dresses in various publications in 1809.

Mrs. Janiere : 1798-18? – New Bond St.

Mrs. Janiere made a rapid rise to trendiness as a milliner dressmaker to the beau monde, not least because of her glamorous appearance. Her reputation came under attack in early 1800, possibly from envious competitors, and she was maligned as having learned her trade in a Parisian house of ill repute. On 23rd March, 1800 she advertised in Bell’s Messenger that “the intended purpose of such insinuations will not be productive of the desired effect, as that Lady still means to continue her tasteful exertions for the gratification of the Beau monde…”

Trade card of Miss Jones (c. 1808) © Trustees of The British Museum

Miss Jones: 1806-1811 At: 50 New Bond St.; 19 St. James St.; 23 Gt. Portland St.

Miss Jones was formerly at Miss Barry’s house and continued in business as one of that notable modiste’s “successors.” She was a milliner dressmaker to the Duchess of York and was patronized by a mostly beau monde clientele. In December 1808 she relocated from New Bond St. to St. James St.

That month, a Half Dress ensemble of hers was featured in Mrs. Fiske’s Records of Fashion described as a “Donegal dress… of rich figured sarsnet of gold and scarlet, to sit close to the shape, richly trimmed with swan-down.” A “Corunna scarf” was worn over the dress. Several of her gowns were featured in that publication in 1808 and 1809. She was listed in Holden’s, 1811.

Madame Kerbault : 1818-? – 47 Jermyn St., St. James

Madame Kerbault, claiming to be a big deal modiste in Paris, established a shop in Jermyn St. with her sister, Madame Holland in May 1818.

Mrs. Susannah Lacon : 1798-1823 – 19 Berkeley Square, 16 Albemarle St.

Like many modistes, Mrs Lacon (ca. 1781-1861), ran her business from her home and had various employees living at her address also. She had a long career as a top name in Regency fashion. Her husband John played a role in her business, selling hair products and gentlemen’s goods, and dealing with delinquent accounts and troublesome employees.

Mrs. Lacon first made a name for herself, not for her dressmaking, but as a witness in the lurid court case Henderson v. Sir H. Vane Tempest (his actual name) for “Criminal Conversation with the Plaintiff’s Wife” in 1799. Henderson, having discovered that “his bed had been dishonored,” sought damages against Tempest, one of the men she had been involved with. As a witness, Mrs. Lacon testified that Mrs. Henderson had a rendezvous with yet another man at her show room and vanished to the upstairs drawing room with him, where improprieties occurred. The judge, Lord Kenyon, noted that Mrs. Lacon carried no blame in the matter and had conducted herself with “great propriety.” In the end, he took issue with Mr. Henderson’s conduct in permitting his wife to do as she pleased, and found in his favor, but awarded damages of only one shilling. Tempest was, after all, not Mrs Henderson’s first “seducer.”

Mrs. Lacon had a business partner at the time, a Miss Holden, who left in 1801 to set up her own establishment, taking an employee, Miss Theobald with her. They briefly operated at 56 St James St. but went out of business.

Mrs. Lacon seemed to have mixed luck with her employees. A few years later, in 1807, she was in court once again in the trial of her trusted forewomen, Jane Masenau, for theft of lace and other items. Jane had been with her since 1805, and as items vanished, Mrs. Lacon suspected other young women who worked for her, but the police found no evidence that they were involved. At the end of the London season in 1807, Mrs. Lacon went to Brighton to serve the resort clientele. Jane, the only employee who accompanied her, foolishly stole items there. Mrs. Lacon informed the police investigator, who found receipts for stolen goods Jane had pawned. She was found guilty and sentenced to death, but the harsh penalty caused a public stir and the king pardoned Jane soon after.

Six months later, Mrs Lacon sued Jane for the cost of the stolen goods, and lost.

In May 1817, Mrs Lacon and her husband moved to 13 Albemarle St. and resumed business there. 1822 finds the Lacons in court again, this time to recover unpaid bills for dresses supplied to the wife of one Henry Higgins, a suit they won.

Eventually Mrs. Lacon succumbed to competition from ready-to-wear merchants, and converted her home to a boarding house, which she ran well into her widowhood. She remained listed as a milliner in the Post Office directories of London as late as 1846.

Mrs. (Margaret) Ann Lanchester / Madame Lanchester : 1800-1810 – 37 Sackville St., 17 New Bond St., 59 St. James St.

In and out of bankruptcy, Madame Lanchester is one of the best known modistes of the early 19th century. Read more…

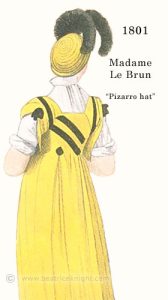

Madame Le Brun : 1792-1805? – Berkeley Square

Madame Le Brun : 1792-1805? – Berkeley Square

Among London’s most celebrated milliner / modistes at the turn of the century, Madame Le Brun was mentioned in Richard Phillips Fashions of London and Paris on multiple occasions. In addition to designing and making fashions to order for an upscale beau monde clientele that included nobility and royalty, she also stocked one of the city’s largest ranges of fine fabrics, laces, and trims. On May 5, 1798, the Morning Post reported Madame Le Brun, having filed for a patent on a “straw skull cap” of her design, had employed over 100 young women to manufacture this hat. Le Brun was also at the center of a fracas involving Lady Hamilton, whom she supplied with dresses, hats and accessories while her ladyship was at the court of Naples. Madame Le Brun was among the trade suppliers to the Queen who illuminated their shop-fronts in May, 1799 to celebrate the Duchess of York’s birthday. The Evening Post (May 6, 1799) reported her address “shone forth most splendidly, the whole front of her house being an attractive display of flambeaus.” In January 1801, her wove silk “Pizarro” hat and feathers were the must-have accessory for the élégante about town.

Mrs. Lockwood : 1816-182? – 11 Soho Square

Mrs. Lockwood was a dressmaker and milliner who worked from her home, specializing in making over gowns and hats with new trims, and creating fancy dress. Her niche strategy was especially pragmatic given the large number of genteel and middle class women who did not have lady’s maids and needed to practice economies in their dress. At the end of the London Season, she packed up her wares and went to Brighton running, as a number of modistes did, a travelling trunk show of sorts to cater to clients have seaside vacations at the fashionable resort. She would typically return to town in November and place a notice in the papers alerting her clients.

Regency evening dress. By Mrs. Marchant. The Repository, June 1817.

Mrs. Elizabeth Marchant (née. Ellis b. 1792-d. 7 June 1838) In business 1815-1825 At: Bennett St.; 40 Gerrard St. Soho

After working through an apprenticeship and then dressmaking in her own right from 1813-1817, Elizabeth Ellis ran her business from Bennett St. until 1815, when she moved to the large Marchant family home in Gerrard St. Advertising in the Morning Post, (19 April 1815) she reminded customers that her prices were twenty percent lower than other houses and that “—at all times inventing her own fashions, enables her to offer productions not to be seen at any other house.” Several of her designs were featured in Ackermann’s Repository in mid-1817.

It seems she lived in a common-law marriage with her husband Jonathan initially. He was a widower when they met. After they married in August 1818, she continued her dressmaking business from the large Marchant family home. Jonathan Marchant was a coal merchant to wealthy and noble families and would eventually become coal merchant to Queen Victoria. Mrs. Marchant made pleasing gowns for the prosperous middle-class and gentility. She was unlucky in her hopes of having children and continued to work through the 1820s. After 1825, her health declined and it seems she slowly wound down her business. She died in 1838 she died, aged 46.

Her husband married as soon as the mourning year ended and went on to have many children with his second wife. The family remained prominent London merchants.

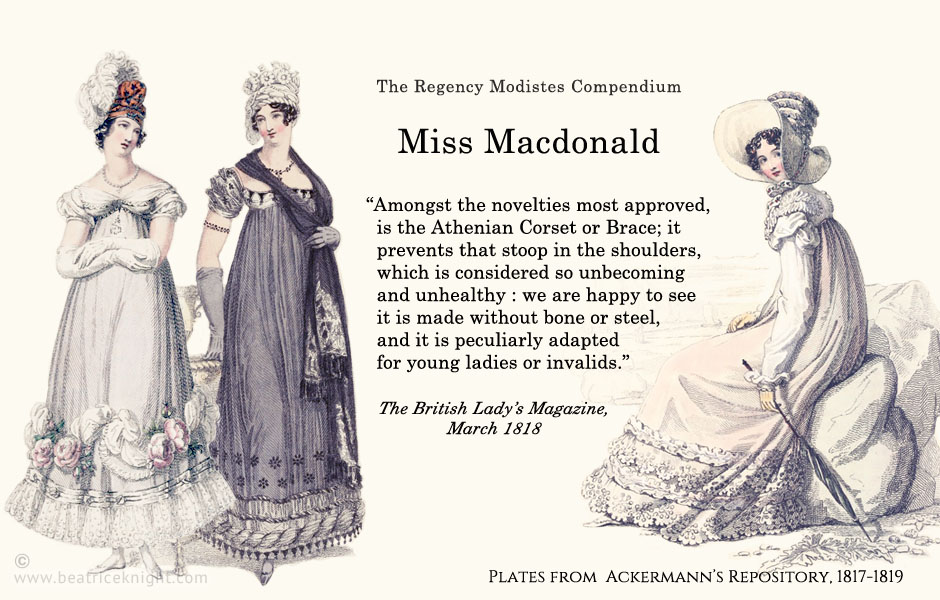

Miss E. MacDonald : 1816-1819 -Wells St., 50 South Molton St.; 29 Great Russell St. Bedford Square

Miss Macdonald (later Mrs. Smith of Old Burlington St.), whose name occasionally appears misspelled as ‘McDonald’, was a leading modiste during the 1810s. She was featured in multiple fashion magazines, and also promoted the ‘Athenian corset’ which she “invented.” Read more…

Mesdames MacPherson: 1820-18? – 28 Albemarle St.

Sisters who combined skills in millinery and dressmaking.

Miss Millman : 1809-1814- Half Moon St., Piccadilly

Records of this dressmaker are uncertain. A costume attributed to her in Ackermann’s Repository in January, 1810 was actually a design of Miss L Collins. It seems that Miss Millman may have been an employee of Miss Collins, or the business partner who joined her in 1809 at the Half Moon St. address. If so, she probably took over the the shop when Miss Collins went out of business in 1811.

Madame de Montmorency : 1825 address uncertain

A promenade dress of hers was featured alongside Miss Pierpoint’s latest creation in the Ladies’ Monthly Museum, June 1825. This dressmaker may have adopted the last name of the Princess de Tingry de Montmorency for marketing purposes, the princess having excited attention after the publication in 1822 of the scandalous Memoirs of Lauzun. The Viscount de Montmorency, French Minister of Foreign Affairs, was also a household name at the time.

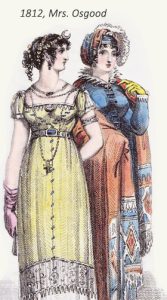

Mrs. Osgood: 1812-18 -Lower Brook St. Grosvenor Square

Mrs. Osgood: 1812-18 -Lower Brook St. Grosvenor Square

Mrs. Osgood formerly worked for Mrs. Lanchester, and effectively took over that premier modiste’s clientele after she went bankrupt. She signed a contract for a year long promotion on Lady Day 1812 with the Lady’s Monthly Museum, who had this to say of her: “… the elegance of her taste, her works, while the pupil of Madame Lanchester, and since she has left that lady, are too well appreciated by every woman of fashion to need any comment here.” Her designs appeared in that publication from April 1812 – April 1813. I found a death record for a Mrs. Mary Osgood, who died aged 46 in October 1824, in an infirmary.

Miss Mary Maria Pierpoint : 1819 – 1829 – Henrietta St. Covent Garden, Edward St. Portman Square

Inventor of the Corset a la Greque., Miss Pierpoint was one of the two modistes who dominated London fashions in the 1820s. Read more…

Miss E. Place: 1827 – 41 New Bond St

Miss Place took over the premises of Miss Gardener, another milliner/dressmaker who catered to a respectable middle class clientele. In 1827, she advertised (London Morning Post. May 14) her return from Paris with new fashions. Miss Place made a little extra money handling advertisements for ladies’ maids, governesses etc (London Times June 5, 1825).

Mrs. Pontet : 1805 – 1825 – 134 Pall Mall (late of Sackville St.)

Mrs Pontet, along with Mrs. Triaud, was one of a handful of premier Regency modistes who did not need to promote herself. She was the daughter and heir to the House of Toussaint & Co., which had been serving high society since 1775, including court dressmaking for the Princess of Wales and the Duchess of York. After the death of Mrs. Toussaint, she moved the business to Pall Mall and traded successfully under her own name until January 1825, when she sold to Miss Rutherford of 45 Pall Mall in January 1825, whom she named as her successor. Mrs. Pontet may have married to Mr. Pontet, of Fribourg and Pontet, tobacconists and snuff-makers to the king and royal family, whose shop at 134 Pall Mall was located near hers. In 1821, Mrs Pontet fell victim to Richard Jago, a burglar who carried out a racket in forged checks. He was executed for his crimes in January 1822.

Miss Powell : 1813 – 18?? – Piccadilly

Mentioned as having taken over Mrs. Franklin’s business, Miss Powell is credited by La Belle Assemblée (December, 1813) as being the “inventress” of the “Kutusoff mantle.”

Mesdames Powley and Harmsworth: 1814- 18?? New Bond-street.

The mesdames promoted their designs in the Ladies’ Monthly Museum from June-September, 1814.

Mrs. Reina: 1815-1817 At: 6 Great Newport St., Soho

A milliner who also made riding habits and other garments, Mrs. Reina was startled in 1817 to discover clients had heard rumors of her demise. She placed an ad in Ackermann’s Repository, May 1817, assuring them that she was still alive and ready to sell them hats and other necessities. It appears she went out of business around that time.

Miss Roberts : 1811- 18?? – 27 Great Queen St., Lincoln Inn Fields

Miss Roberts had a small clientele mostly in her locale. She was listed as a dressmaker in Holden’s London and Country Directory, 1811

Mrs. Mary Robertson : 1801- 18?? – 14 Dover St., Blackfriars

Mrs. Robertson described herself as a milliner and mantua maker, and had a modest clientele in her locale. For extra income, she lent her name to promotional letters published in support of Dr. Fothergill’s drops.

Miss Catharine Row : 1790s – 1807 – 52 Great Russell St., Bloomsbury Square

Miss Row was a milliner and fancy dressmaker. She was still in business when she died in January 1807.

Miss Rutherford : 1822- 18?? – 45 Pall Mall

Miss Rutherford ran a modiste establishment in Pall Mall which became enlarged when she purchased Mrs. Pontet’s stock and goodwill in 1825.

Mrs. Sarah Schabner: 1811-1814 – 26 Tavistock St., Covent Garden.

Mrs. Schabner, a “robe and habit maker to Her Majesty” (Holden’s, 1811) specialized in evening and equestrian wear. One of her riding costumes was featured in Ackermann’s Dec, 1811, and two evening gowns appeared in La Belle Assemblée, February 1812 and January 1814. She rarely advertised and her creations clearly targeted an upscale clientele.

Mrs. Southard : 1795-18?? – 80 Oxford St.

Advertising herself in May, 1798 as fancy dress maker and milliner to the Duchess of York, Mrs. Southard carried a large range of millinery, fabrics, linens, corsetry, accessories, and ready-to-wear dresses in addition to made-to-order garments.

Mrs. Mary Sowerby (formerly Miss Lockwood of Brighton): 1800-1815 At: 37 and then 65 and 70 New Bond St.; Clifford St.; 59 St. James St.

Mrs. Sowerby was one of London’s leading modistes between 1800 and 1810. She was listed in Holden’s Annual London and Country Directory, 1811. Vol.1.

Prior to marrying milliner Thomas Sowerby in May 1800 (Evening Post, 2 May), she was Miss Lockwood, an upscale Brighton modiste with a London shop at 37 New Bond St. After she formally notified her London clients (Times, Nov 5, 1800) of her status as Mrs. Sowerby, she and her husband purchased the lease on a large house at 70 New Bond St. Mrs. Sowerby inserted a notice in the Morning Post on 14 March, 1801, advising clients of her removal there and the “neat” style in which she was fitting her new shop.

She had a colorful career which is explored in more detail in the Regency Modistes’ Compendium.

Miss Slarke (variously spelled Starke and Slark in newspapers) : 1802-1809 – 52 Conduit St.

Miss. Starke lived above her shop in Conduit Street with her family, including her mother, Mrs. Starke who seemed to assist in the business. She catered to a fashionable clientele and also took her stock on the road to resorts after the Season ended. Just before she set out for Brighton in July 1809, a fire engulfed the building and destroyed her entire stock. She behaved heroically during this conflagration, rushing to warn family members who were all in bed and escorting them down to the street, where they stood in heavy rain in their nightclothes. Newspaper reports acknowledged that the flames were so great by this time, her family would have perished if not for her quick action and composure. Unfortunately, the fire seemed to wipe her out and I could find no record of Miss Slarke re-commencing business.

Mrs. W. Smith (see Miss E. MacDonald): 1818-1821 – 15 Old Burlington Street

A number of Miss MacDonald’s designs were featured under her married name ‘Smith’ in the British Lady’s Magazine, Sept-Dec 1818, Ackermann’s Repository, Jan 1819, Ladies’ Monthly Museum, May 1819.

Mrs. Stephens : 1804?-181? – Wigmore Street

In 1809 Mrs. Stephens was appointed dress and corset-maker and milliner to the queen and the royal princesses. She had been in business for some years by that time, discreetly serving mostly a very upscale clientele. A widow with a large number of dependent children, she was praised in the notice of her royal patronage (Morning Post. June 5, 1809) for her “well-known elegance of fancy and luxuriance of invention in the Fashionable World…” and for her entrepreneurship in being the successful sole support for her children.

Miss Stewart : 1818 –

Mrs. Thomas : 1815-1822 -Wellington House, 193 Fleet St. (probably worked at ‘Wellington Rooms’ corner Chancery Lane and Fleet Street from 1800, which is where R Thomas initially located his warehouse business)

Mrs. Thomas specialized in evening and carriage dresses. Her designs were featured in the British Lady’s Magazine, July 1817, and La Belle Assemblée, February 1818. She was part of the Thomas family who ran the large, successful Thomas warehouse (see warehouse list below) for many years. Although she designed many of the ready-to-wear pelisses and traveling costumes for her family warehouse, she was rarely featured as a modiste in her own right. Given the scale and success of the warehouse, it’s safe to say her fashions must have been seen on many prosperous middle class matrons of the time. The Thomas warehouse went out of business in 1822. I can find no information about Mrs. Thomas after that date.

Mrs. Margaret Triand: 1802-1817 – Bolton St.

A dressmaker to royalty, Mrs. Triand (widely misspelled as Triaud) was among a handful of leading Regency modistes who had no need to promote herself by advertising. She made Princess Charlotte’s wedding dress in 1816 and many gowns for her vast trousseau, which cost an astronomical £10,000 (roughly $800,000 in today’s money). She was at the top of her game from 1812-1816, and almost certainly retired in comfort after receiving the commission of a lifetime.

I have found no evidence that she continued dressmaking after the princess was married. It seems likely that she retired. Her name appears in the London land tax records for her Bolton St. address. These show her husband Louis (also spelled Lewis) paying taxes on the property until 1828, and Mrs. Triand listed as paying in the following years until 1839.

Madame Viedement: 1816?-182? – 7 Conduit St.

Listed in the Pigot & Co London business directory, 1822, Madame Viedement was the trade name adopted around 1820 by a milliner/dressmaker who seems to have had a checkered career. I am researching her at present and will hopefully verify her full identity as this project continues.

Mrs. Villars : 1807-181? – 6 Lower Gower-street, Bedford-square.

Mrs. Villars advertised via the daily papers to price-conscious clients from 1808 onward. In an ad. in 1809 (Morning Post. March 22), directed at “ladies of the highest rank,” she promoted her Alcantara Hat and Mantle, a Spanish style costume suggested for opera or evening events, also featured that month in La Belle Assemblée.

The Miss Walthers : 1808 – 1818 – 75 Margaret St. Cavendish Square

The earliest fashion plates of the Walthers sisters’ designs appeared in the February and April issues of La Belle Assemblée, 1809. They were very well known modistes who specialized in evening wear, and had their most successful years from 1809-1814. The dress (left) was described in Ackermann’s 1812, as: “Imperial blue sarsnet, shot with white, with a demi-train, ornamented with fine French lace…the robe left open a small space down the front, and fastened with clasps of sapphire and pearl over a white satin slip petticoat.” The ensemble was completed with a twisted shawl of fine white lace.

One of the sisters became ill around 1812 and they began tapering back their activities. I found no mention of them after 1818.

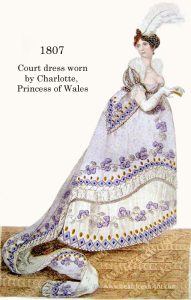

La Belle Assemblée, July 1, 1807. Retinted by Beatrice Knight.

Mrs. Webb : 1805 – 1811 – Pall Mall

Mrs. Webb made ball and court dresses for women of rank. Her best-known design was the lavish court dress (right) she made for Charlotte, Princess of Wales in 1807, which was heavily fringed in silver and embroidered with emeralds, topazes, and amethysts in a grapevine pattern. Worn just once for the Queen’s Birthday court that year, its cost would have been in the region of $100,000 in today’s dollars.

Mrs. Elizabeth Williams: 1790s – 1800 – 20 Cranbourne St., Leicester Square.

Mrs. Williams was a reputable but small-scale milliner dressmaker who catered to a mostly middle-class clientele. She went out of business quietly in November, 1800, auctioning all her stock and the leasehold of her premises.

Miss Wing : ca.1810-1820 – 59 St. James St.

Miss Wing took over the lease and fittings of the shop previously operated by the famed Madame Lanchester, who went bankrupt (Mrs. Osgood having taken over the stock and clientele). She was a milliner and dressmaker to Queen Charlotte, and also made high end gowns for women of rank to wear at court appearances like the Queen’s “drawing rooms.” In 1818, she made the wedding dress and some 30 trousseau gowns and pelisses for Princess Elizabeth, on her marriage (at age 47 years) to Frederick, Prince of Hesse-Homburg. The princess took the lavish trousseau with her to Germany, and in 1820 she became the Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg. Miss Wing also made the dresses worn to the wedding by Princess Augusta and the Duchess of Gloucester.

Mrs. Wirgman : 1800-1811 – Hanover St., Hanover Square

The Wirgman family were well-known dressmakers who published their own fashion plate handouts, which were also featured in the Ladies Monthly Museum. They established their business in the late 18th century – year uncertain. I’ve traced published fashion plates of theirs back to 1800 and am working on locating earlier examples. I have not been able to ascertain whether they were connection of the famous Wirgman jewelers of the same period.

Warehouses and Others

Mr. John Arpthorp – 278 High Holborn – Stays and corsetry.

Mrs. Barclay – staymaker. Ackermann’s, June 1816, and possibly in La Belle Assemblée, March 1807 for her “considerably cheaper wares”

Mr. Barry – a tailor who specialized in riding habits.

Mr. S Clark – 37 Golden Square – Equestrian habits, coats, pelisses and clothing made to order on short notice. Ackermann’s, May 1815

Mr. A M Cohen -26 Widegate St. – Accessories

Ann Abraham – 53 Houndsditch – Ann Abraham operated a family business first established around 1800, supplying childbed linens, household linens, ready-to-wear garments, children’s wear, and servant’s liveries. (Underhill business directory, 1822) She appears to take over the business from her father and during the 1820s she advertised routinely in the Morning Post. In the mid-1830s Ann operated the business with her son or nephew Gardiner Abraham (Pigot & Co business directory, 1836). The Abrahams were a well-known Jewish family in East London trade circles, with members working in various business. I am trying to untangle Ann’s family tree, to separate her from other Abraham families active in business at the time.

Deacon and Wilkinson – 32 Bond St. (late 1790s- ) – Fancy dress, millinery, linens, muslins, shawls, muffs, tippets, reticules/ridicules, and other accessories.

Dudden and Bell – moved in April 1800 from 421 Strand to 39 Oxford St. (taking over the late Mr. Gedge’s premises) – All types of fabrics, ready-made attire and accessories.

Dyde and Scribes – Muffs, tippets, reticules/ridicules, and other accessories.

Everingtons British and India Shawl Warehouse – 10 Ludgate St. near St Pauls.

Gibbon & Co, formerly Gibbons Cheap Woollen Drapery and Clothes Warehouse – 176-183 Fleet St. ; 16 King St., Covent Garden – (1797-18??) Wide variety of gentlemen’s attire, servants liveries, fabrics, and accessories. Terms were “ready money” only.

Ham’s Dress and Muslin Warehouse – 19 st. James St (late 1790s- ) – Wide variety of ready-made dresses, pelisses, cloaks and accessories

Hammans Milliners – 4 Mortimer St. The multi-generation millinery and dressmaking business ran by the Hammans women was a fixture in Mortimer St for about 40 years, from the mid-1820s to around 1860. The business was established by sisters Maria and Rebecca Hammans. They dissolved their partnership in 1834, but the shop was taken over by Anna Maria Hammans, who ran it with her dressmaker sister Elizabeth Abrahall, who then inherited the business after Anna died, and kept it running as Hammans’ until it changed hands in 1860/61.

Harding Howell – 89 Pall Mall. One of the first department store style warehouses, Harding Howell was a glimpse into the future. A large, elegant store, it attracted upper echelon women and provided an elegant one-stop shopping experience that would later become synonymous with the likes of Selfridges and Harrod’s. In my forthcoming (May, 2023) Regency family saga, Alverstone, the Winford family takes their young American cousin on a shopping trip to this store, which I researched in depth for accuracy.

Millard’s – 16 Cheapside. Later known as ‘Millard’s East India and Foreign and British Warehouse.’ Operated by J Millard, this large retail and wholesale operation specialized in East India Company goods, supplying household linens and other items, fabrics and haberdashery, and ready-to-wear fashions for men and women. It’s possible that Mary Ann Bell, nee Millard, was a member of the family and developed her skills and interest in ladies’ fashions through that business. Millard established his business by taking over the house and stock of draper Mr. Denning at 16 Cheapside (Morning Post, 19 May, 1804). He initially described himself as a linen draper and furniture printer, but soon branched out. He was perhaps the most prolific advertiser of the warehouses. It’s rare to see an 1805 daily paper without one of his advertisements.

Mrs. James – 104 Oxford St. Ran her Italian Corset and Ready-Made Warehouse in the late 1810s, offering a large range of undergarments and ready-to-wear targeting travelers especially.

Lewis & Co – 195 and 197 Regent Street. Specialized in India shawls, wraps, cloaks, and ready-to-wear dresses.

Mack and Bennett

Newtons Shawl Warehouse – 14 Leicester Square. (1799-18??) – specializing in Norwich shawls, linens, fabrics and threads.

C. Price – 221 Strand. Fans, parasols, umbrellas, canes. Ackermann’s, June 1816

Radford & Co – Fleet St., Chancery Lane. Gentlemen’s ready-to-wear breeches and coats. Travel wear.

Radford & Co – Fleet St., Chancery Lane. Gentlemen’s ready-to-wear breeches and coats. Travel wear.

Robarts, Plowman & Snuggs. 1 Chandos Street. From the early 1800s, this smaller warehouse advertised ready to wear dresses, and dress lengths from 3 and 6d to 4 guineas per yard (Morning Chronicle, 30 June 1804)

Thomas & Co – Wellington House, 193 Fleet Street ( formerly R. Thomas, corner of Chancery and Fleet Street – London Times, 7 Dec. 1802) Large warehouse, notable in the 1810s. Millinery, ready-to-wear, fabrics, and accessories. Hired many dressmakers. Advertised profusely. In March 1822, they closed their business, and had a massive sale of their stock at Wellington Rooms, Chancery Lane.

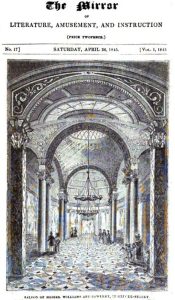

Williams and Sowerby – Commerce House 61-62 Oxford St. Established 1828, this vast warehouse specialized in imported and English silks, haberdashery, hosiery, gloves, ribbons, laces, and the usual drapery. They became a heavyweight, taking over nearby premises at 3-4 Wells St. as their business expanded. Their partnership ended in 1851, but not before they had carried out an impressive refurbishment of their building, as seen (left) in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, April 26, 1845

Resources

Baldwins London Weekly Journal. London

Bell’s Court and Fashionable Magazine. J.Bell. London

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The British Lady’s Magazine. D. Mackay. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

The Mirror of the Graces. Crosby & Co. London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London

The Edinburgh Advertiser. Edinburgh.

The London Express. London.

The London Morning Post. London

The London Pilot. London.

The London Star. London

The Morning Chronicle. London

The New Times. London

The London and Country Directory , 1811

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. New York. Garland, 1989.

Paviere, S. (1936). BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES ON THE DEVIS FAMILY OF PAINTERS. The Volume of the Walpole Society, 25, 115-166.