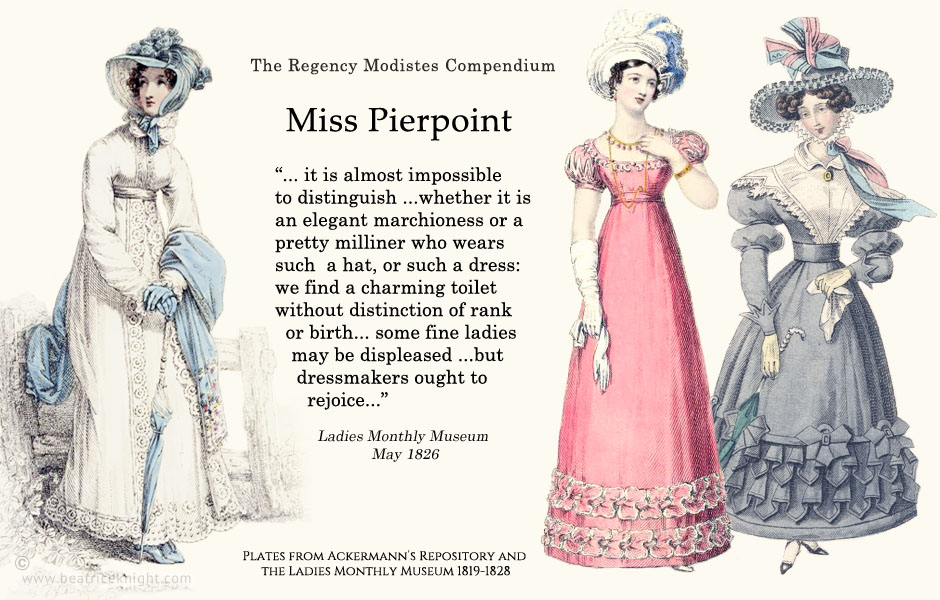

The self-declared “inventor of the Corset à la Greque,” Miss Pierpoint was the busiest marketer of all the Regency modistes, with over 230 of her dresses appearing in fashion plates across multiple publications from mid-1819 until she went out of business ten years later.

Miss Mary Maria Pierpoint (1787-1835)

1819-21: 9 Henrietta St. Covent Garden

1821-29: 12 Edward St. Portman Square

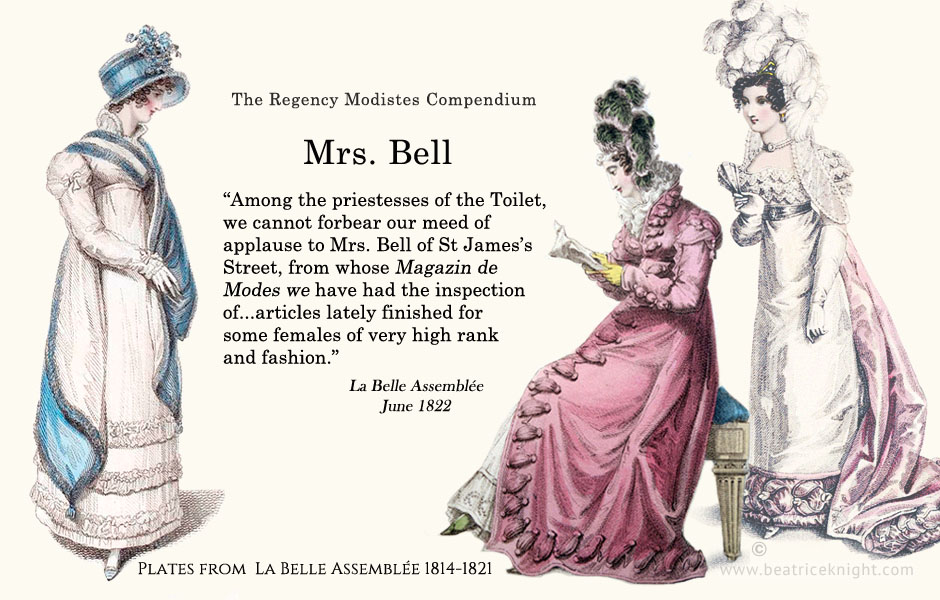

Miss Pierpoint was perhaps the most “modern” modiste of the Regency era. She understood how to boost her brand through name recognition, targeting both the élégantes of the ton and the prosperous middle-class women who wanted to look like them. Her dresses appeared in Ackermann’s Repository from 1819-22 and she bought out the promotion spots for virtually every month in the Ladies’ Monthly Museum for the entire 1820s, barring 1829, when her business hit the skids. Between 1819 and 1825, her fashions even appeared occasionally in La Belle Assemblée and the British Lady’s Magazine. She was one of the two modistes who dominated London fashions in the 1820s. The other was Mrs. Mary Ann Bell.

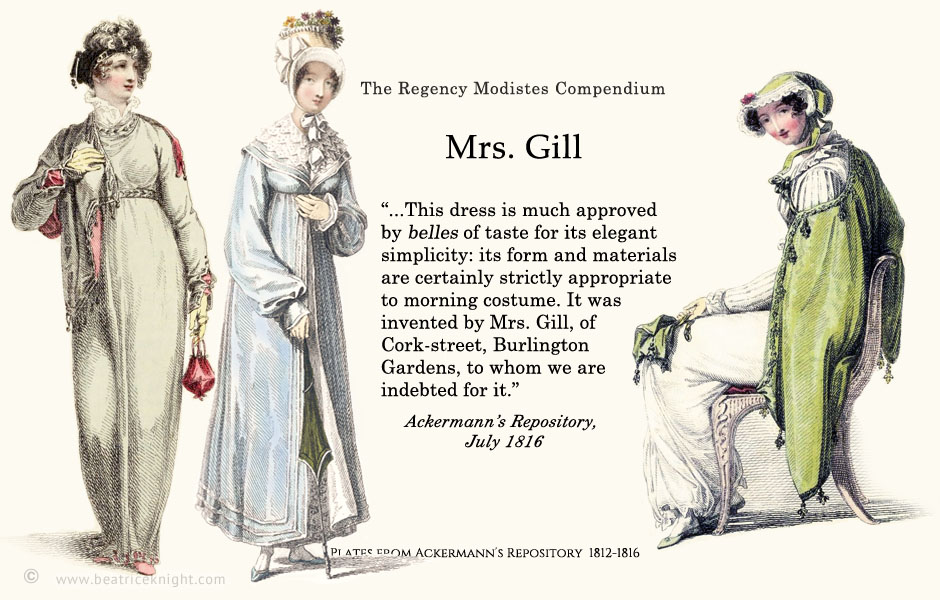

Was Mrs. Bell Her Mentor?

No one launches a fashion empire without some experience. Miss Pierpoint would have spent several years working as an “improver” or apprentice for another modiste before striking out on her own. It’s easy to conjecture, based on various clues, that she may have been one of the many young women employed by Mrs. Bell. If not, she certainly followed Bell’s example very closely:

- Miss Pierpoint’s skills in corset design must have been developed somewhere, and Mrs. Bell was one of only a small handful of modistes in London who ran a profitable sideline in corsets and stays; she also employed more apprentices than most of her competitors. Did Miss Pierpoint sew stays for Mrs. Bell, and come up with her own idea for a new type of corset in the process? Did she decide not to share her concept, but to launch a business of her own around it instead?

- Mrs. Bell made a trip to Paris in 1817 and a Parisian sensibility was evident in her subsequent designs. Is that how Miss Pierpoint acquired her own preference and skills in Parisian styling?

- Miss Pierpoint’s first few designs, when she started out in 1819, closely resembled certain styles Mrs Bell launched in 1816-1818. Did she sew those designs, originally, as an employee of Bell’s and later use them for her own business?

- From the get go, Miss Pierpoint targeted the same mix of upper and middle class clientele as Mrs. Bell, a sound business strategy that buffered Bell against the risks of supplying costly fashions only to the most upscale clientele, notoriously slow to pay their bills.

- Bell used media power effectively, becoming an “influencer” through her columns at a time when most modistes only ran newspaper ads. Pierpoint adopted the same unusual media strategy as Bell.

As the first signs of a sea-change in fashion became evident by early 1819, Miss Pierpoint clearly saw the shift toward tighter bodices and longer waists as an opportunity. Within months, she launched her business, declaring herself the “inventor of the Corset à la Greque.” She reinforced that credential in every promotional spot for the next decade. The name became synonymous with high-end corsetry; so much so that a century later various “La Greque” corsets were still on sale, and the name was even adopted by an American company for their lingerie brand – a lasting testament to Miss Pierpoint’s marketing smarts.

Miss Pierpoint’s Fashion Sensibility

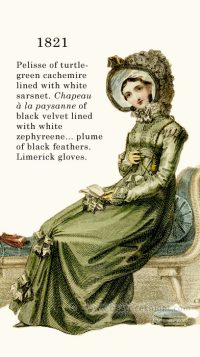

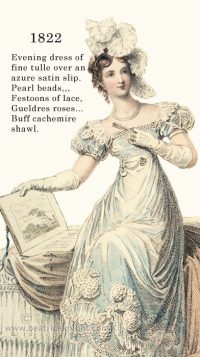

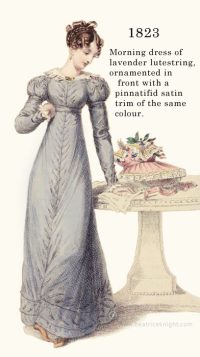

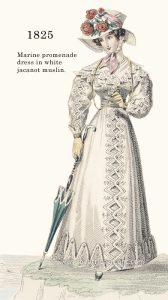

Miss Pierpoint entered the fray in 1819, on the cusp of a major transition in British fashion. The soft, neo-classical lines and Empire silhouette of the past two decades were about to be consigned to history. Within a year, high waists would start to plummet. By 1824 bodices had tightened and the the Romantic era silhouette was established, with a more natural waistline, puffed sleeves, and ever-widening skirts. Between 1825-28, this look went on steroids. Natural waists were in. Gigot or leg-o-mutton sleeves were puffed out with expanders and mini-hoops until they appeared to be twice the size of the waist, and skirts were so voluminous that gores were not enough, so extra fabric was gathered into the waistband.

THROUGH THE YEARS – click to enlarge

Miss Pierpoint’s distinctive sensibility became apparent from 1822-23 onward, and her designs were at the cutting edge of the dramatic changes in fashion until she went out of business in 1829. By contrast her earlier fashions, were more generic “safe bets” for a young dressmaker just launching her own business. The very first Pierpoint dresses featured in Ackermann’s appear to carry the stamp of Mrs. Mary Ann Bell, who had run a successful business for the past five years, boosted by her family ties to John Bell, publisher of La Belle Assemblée. Miss Pierpoint conformed to the prevailing Romantic movement taste for flounces in 1819-21 (see above), with designs and detailing that seemed to occupy the same lane as Bell’s.

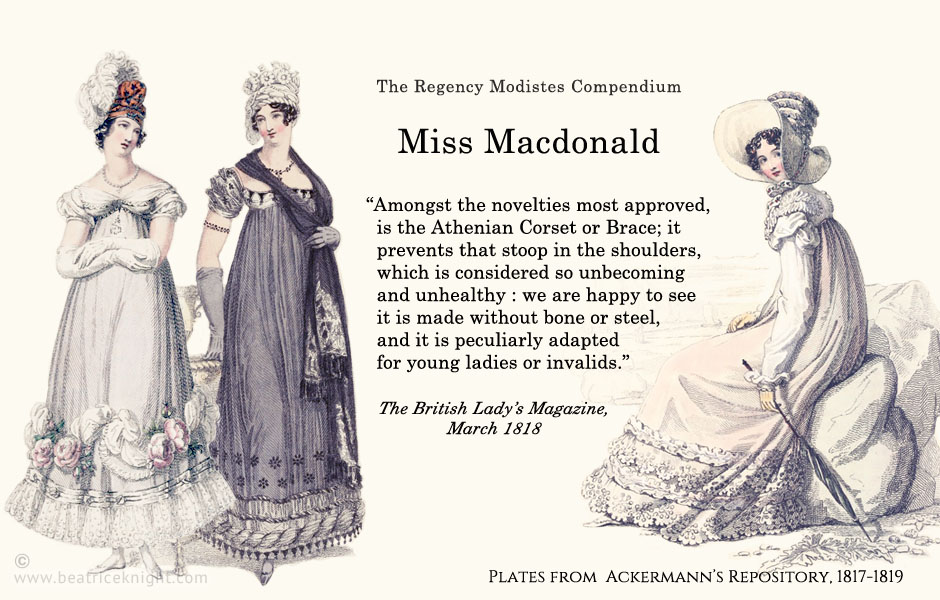

That changed after she relocated her business to Portman Square in 1821. Her styling became more definitive and she seemed to draw inspiration from Miss MacDonald, who had just expanded her operation after several years of success featuring her more Parisian-influenced styles. There is no evidence that Miss Pierpoint ever went to Paris; given her media skills, she would certainly have proclaimed such a visit. However, the influence of Parisian sensibility was evident in her structured detailing and overall chic. While her designs were finely detailed and her silhouette Romantic, if a client wanted flounces of blond lace and bows crammed onto every available inch, she would not find them at Miss Pierpoint’s magazin des modes.

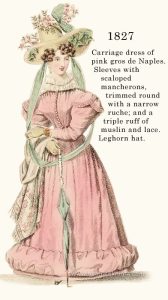

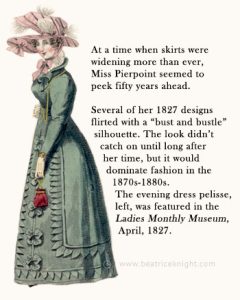

Like today’s top designers, Miss Pierpoint carved out a recognizable look that distinguished her from other leading modistes. Her fashions were emulated by competitors, worn by celebrities, and some of her designs foreshadowed trends ahead of her time. When fashion was all about sleeves and waists, from 1825 onward, she seemed to contemplate the ‘bust and bustle’ silhouette, probably inspired by some French designs of a similar ilk. A number of her gowns, and the corsets she sold to accompany them, seemed to toy with this silhouette, as seen in the 1827 evening pelisse (left).

Like today’s top designers, Miss Pierpoint carved out a recognizable look that distinguished her from other leading modistes. Her fashions were emulated by competitors, worn by celebrities, and some of her designs foreshadowed trends ahead of her time. When fashion was all about sleeves and waists, from 1825 onward, she seemed to contemplate the ‘bust and bustle’ silhouette, probably inspired by some French designs of a similar ilk. A number of her gowns, and the corsets she sold to accompany them, seemed to toy with this silhouette, as seen in the 1827 evening pelisse (left).

She produced her share of giddy gowns through 1828, which reflected the excesses of the late 1820s. However her designs occupied the tasteful end of a spectrum that veered toward the garish and over-blown.

Unfortunately for Miss Pierpoint, talent, good quality and marketing smarts were not enough when upscale modistes came under siege by the new breed of mostly male ready-to-wear vendors. Many women who once ran independent dressmaking businesses went broke and ended up working as seamstresses for warehouses, typically earning less than a servant.

Financial Affairs

The socio-economic currents in the late 1820s placed modistes in a difficult position. On the one hand, middle class prosperity expanded the market for high-end clothing; on the the other hand, competition for that market exploded. Modistes no longer had a stranglehold on quality. Fashion warehouses – early incarnations of department stores – beefed up their ready-to-wear options and offered inexpensive made-to-order and alteration services. Why pay a fortune for a snooty modiste to look down her nose at you, when you could dress like a queen – and get treated like one – for half the cost?

At a time when every dress demanded voluminous amounts of fabric, modistes had to carry a crippling level of costly stock, and could ill-afford to offer the generous credit terms the “nobility and gentry” continued to expect. Famous for not paying their bills, these clients were the ruin of many modistes, and almost certainly played a role in Miss Pierpoint’s fate. While Mrs. Bell was willing to take a debtor to court, Miss Pierpoint never took such action; unlike Mrs. Bell, she did not have the backing of a prosperous husband.

She’d had her first brush with insolvency in 1821, hitting a crunch period after making the initial big investment in establishing and promoting her business. She survived, and in June 1821 she relocated her shop from Henrietta Street to a more upscale address in Portman Square. The war had been over for five years, the industrial economy was exploding, and with it middle-class prosperity.

Lady’s Magazine, 1828. Recolored by Beatrice Knight.

Miss Pierpoint targeted those middle class customers through monthly promotions in the Ladies Monthly Museum and the Lady’s Magazine through the mid-1820s. By that time her main rival, Mrs. Bell switched from promoting her designs in La Belle Assemblée, to her husband’s lavish new magazine, The World of Fashion and Continental Feuilletons (established 1824). La Belle Assemblée was still controlled by the Bell family, but Mr. Bell senior had retired from the business in 1821, handing over the publisher role to Mr. Whittaker. Mrs. Bell appeared to stay on for a while as the fashion editor, sprinkling columns with coy allusions to herself as “the Marchande des Modes to whose taste we frequently accede…” and preventing the magazine from featuring competitors.

Financial woes began taking a toll on Miss Pierpoint in 1827, and she made an extra promotional push, but could not turn her business around. The dinner party dress in the May, 1828 issue of the latter (left) was among the last of her designs ever published. By October that year, she was going out of business.

On 20-24 Feb 1829, bankruptcy proceedings were brought against her (London Gazette). For a time, she struggled to make repayments, but in the end she lost everything. Miss Pierpoint went to live with dressmaker Mrs. Rebecca Smith (who may have been a former employee) and her husband in Regent Street after her business went under. Miss Pierpoint appeared as a witness (Old Bailey. 29 Nov. 1832) when a man stole a dress from Mrs. Smith.

On Dec 10, 1834, the Gazette reports Miss Pierpoint formally assigning all her personal goods and estate to William Kendle and John Williams (drapers and principal creditors) to be distributed to all her creditors. A few months later, Miss Pierpoint died. She was 48 years old and without family. She was buried on 7 April, 1835 at St. Paul’s parish in Covent Garden.

In a side note: her great rival Mrs. Bell was terminally ill by then, and passed away, attended by her loving family, just two months after Miss Pierpoint, on June 13, 1835.

Read More

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann.