By the time ‘Gypsies’ appeared on the pages of Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott and Maria Edgeworth, Romani people had been in England for centuries.

Sidebar: Believing the copper-skinned migrants to hail from Egypt, the Europeans had coined the term “Gypsies” for these migrants. Some consider this pejorative and prefer Rom/Roma or Traveler. However studies of genetics, culture, and language show distinct differences in heritage between the communities of Eastern Europe (predominately Roma), the Travelers (almost entirely Irish), and English and Welsh Gypsies (Romani). To avoid geographic confusion, the broader ‘Gypsies’ is used in this post.

In 1505, records show Gypsies arriving in Scotland, and an “Egyptian woman” was recorded in England in 1514, but DNA suggests there were Gypsies in England as far back as the tenth century. By the mid 1500s, it seemed an influx had arrived, perhaps fleeing harsh persecution on the Continent. Transporting these strangers into the realm, with their ‘olde accustomed develeshe and noughty practices,’ was outlawed by The Egyptians Act of 1554. Over the next decade criminality was extended to anyone who looked or acted like ‘Egyptians’ or associated with them.

Over the next two centuries, tolerance of Gypsies waxed and waned in step with state hostility toward vagrants. Based upon a plethora of laws passed between 1560-1640 vagrancy, unemployment, and vagabonds were seen as the most pressing social problem of the times. Nomadism was also linked to the spread of disease and seditious ideas, with suspicion falling on all ‘outsiders.’ Already targeted by “Egyptian” restrictions, Gypsies were caught up in a general scapegoating of people deemed vagrants.

Egyptian-style Gypsy by unknown Orientalist School artist

Gypsies in the Regency

As the 18th century drew to a close, a shift in perceptions had emerged. No longer defined entirely by their nomadic habits and deleterious vagabond occupations like fortune telling and livestock theft, Gypsies were increasing viewed as a race, and comparisons with Jews became more commonplace, both being seen as “other” in broader English society.

During the Orientalist craze, English would romanticize the supposed Egyptian heritage of Gypsies. The Romantic movement glorified the noble savage, Gypsies came to represent an idyllic connection to nature even as society marginalized and persecuted them as “other.” The mysterious, colorful, romantic Gypsy would become a trope of writers and lorists well into the 2oth century, as encapsulated in Arthur Symons’ 1908 essay In Praise of Gypsies:

“…the Gypsy represents Nature before civilization. He is the wanderer whom all of us who are poets, or love the wind, are summed up in. He does what we dream. He is the last Romance left in the world. His is the only free race.”

Before this transformation, Gypsies appeared in relatively few novels, and typically as vagabonds endangering respectable people. In Emma, Jane Austen describes “a party of gipsies” assailing Harriet Smith and two young ladies on a stretch of the Richmond road, which Harriet had thought “public enough for safety.” When her screaming friends run off, Harriet is left to fend for herself and the “trampers” are “…all clamorous, and impertinent in look, though not absolutely in word.” She is “more and more frightened…” and tries to buy her safety with a shilling but is soon “surrounded, by the whole gang, demanding more.”

As luck would have it, Frank Churchill happens upon her and scares off the group. After the terrifying ordeal he informs Mr. Knightly of “such a set of people in the neighbourhood” and the “frightful news” is known all over Highbury within half and hour. The Gypsies didn’t wait for the law to catch up but “took themselves off.”

context in the laws and social norms of the time. Merely speaking to gypsies or offering them money, as Harriet does, made one criminal by association.

egency authors, Jane Austen and This contradiction was embodied in Sir Walter Scott’s Meg Merrilies, the honorable and heroic Gypsy witch in Guy Mannering (1815), who remains loyal to the family who cast her out. Meg captured the public imagination, inspiring a poem by Keats, a stage show, ballads, paintings, sculpture, the name of a tartan in 1828, and claims of a connection to the real “Meg” by tea shops and alehouses.

Commenting on centuries of outcast status, George Smith wrote in Gipsy Life (1880) “…nothing seems to have been done to improve the Gipsies, except to pass laws for their extermination…” Gypsies were legally banished from England in 1530 and Scotland in 1540. At various times over subsequent centuries they were tolerated or persecuted.

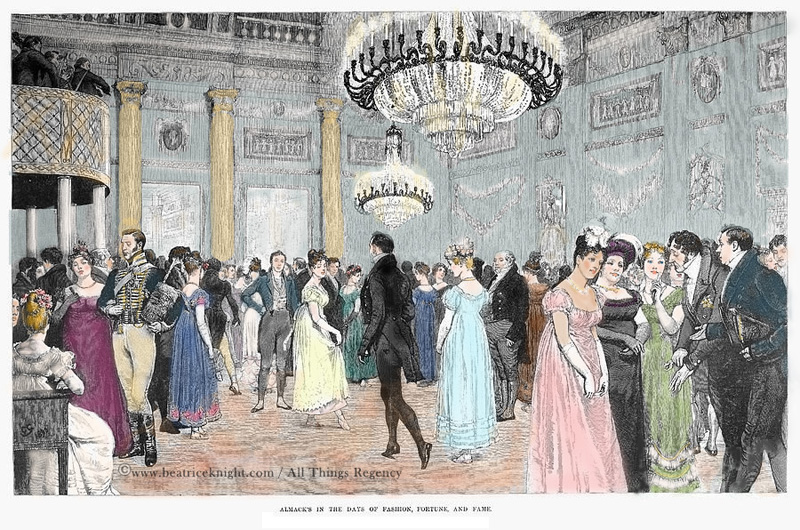

After Lady Mary Wortley Montagu accompanied her husband to Constantinople and 1717 and scandalized Polite Society with her Turkish Embassy Letters, upper class Englishwomen developed a taste for dressing up in glamorized sultana outfits. Fancy dress offered the perfect chance to take a break from stiff etiquette and indulge in harem fantasies. Trade and diplomacy with the Middle East and Turkey

and never rolled out the welcome mat.

Virtually all European Roma can be traced to one wave of migrants who left the Punjab region of northwest India around 1500 years ago.

In Europe: In Switzerland, where Roma are known as Yenish, the authorities set about “eradicating the evil of nomadism at its source, i.e. the children…” in the 1920s. According to historian Walter Leimgruber: “Swiss psychiatrists played a large part in drafting the legislation of the Third Reich….” Ultimately the toxic mix of eugenics and national-socialist ideology led to the extermination of at least 250,000 Roma by the Nazis and their axis partners throughout Europe. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, Roma were hunted for sport in so-called ‘Heidenjachten’ (heathen hunts), in Germany and the Netherlands, with the blessing of the authorities.

18th and 19th century linguists, however, that Romani language is derivative of Punjabi and Hindi.

Engraving of Sarah Egerton as Meg Merrilies in Guy Mannering, April 1817

The English upper and middle class evolved a marriage style that combined alliance and affection, passion and practicality. During the Victorian era the balance of romance and realism became the foundation for English family life among the prosperous and aspiring classes.

Sources / Read More

Austen, Jane. Emma. (1816). The Project Gutenburg Ebook, 2010.

Crowe, David and Kolsti, John. The Gypsies of Eastern Europe. London. Routledge.

Edgeworth, Maria. Belinda. (1801). Oxford and New York: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008.

Frossard, Emilien BD, Rev. Gypsies in France. The Saturday Magazine, Vol.6, iss.165. London, Jan 31, 1835: 39-40.

Gusmão A, Valente C, Gomes V, Alves C, Amorim A, Prata MJ, & Gusmão L (2010). A genetic historical sketch of European Gypsies: The perspective from autosomal markers. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 141 (4), 507-14 PMID: 19918999

Leland, Charles Godfrey. The Gypsies. Boston. Houghton Mifflin, 1882.

Mayall, David. English Gypsies and State Policies. Univ of Hertfordshire Press, 1995.

Nord, Deborah Epstein. Gypsies and the British Imagination 1807-1930. New York. Columbia Univ. Press, 2006.

Smith, George. Gypsy Life. London. Haughton, 1880.

Taylor, Becky. Another Darkness, another Dawn. London. Reaktion Books, 2014.