You’ve overdone the punch at Lady Insufferable’s rout. You need a bathroom break, but it’s 1811. Is a bourdaloue really the only option?

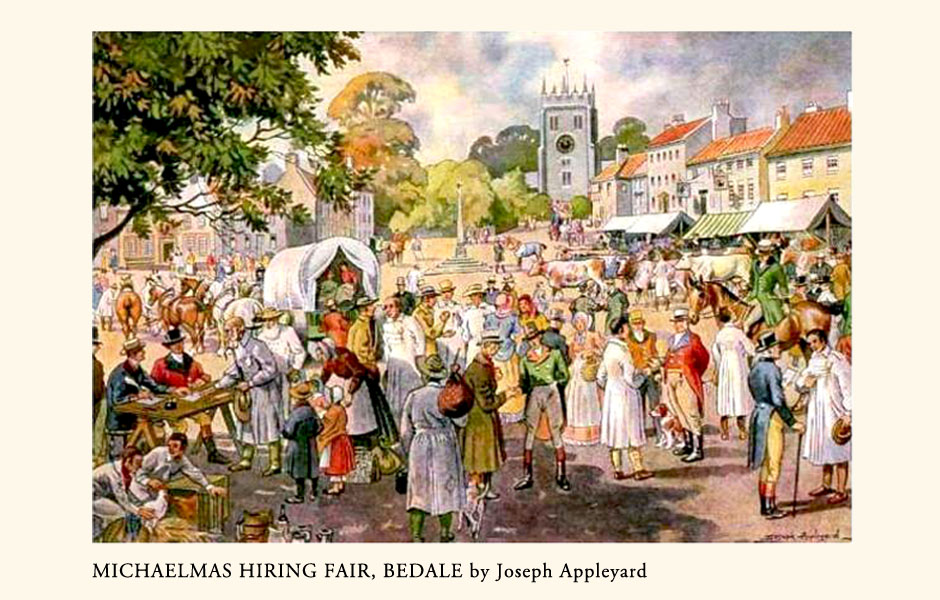

Engraving 1801. British Museum

In the first decades of the 19th century the average English family used some kind of outdoor privy, rather like the one shown in the 1801 caricature (left) of an ‘old maid’ ousted by her squabbling cats.

The “water closet” (as a flush toilet was known) was considered a prestigious luxury. Indoor plumbing barely existed, making the first toilets costly and impractical to install. Still the highest echelons of society wanted to keep up with the Joneses, so great homes increasingly boasted water closets fed by elaborate rainwater cisterns on rooftops. These piped water down into a “valve closet” where gravity would deliver a torrent into the bowl when the valve was opened.

Bramah Valve Closet minus the wood surround and seat

Joseph Bramah sold his patented valve closets in a Piccadilly showroom in the 1780s at 8 guineas a pop – a year’s wage for a maid. The cistern, pipes and installation cost brought the overall price north of £13, yet he claimed to have sold 6,000 of by the end of the 18th century.

Valve closets were famously temperamental, and things got ugly when they malfunctioned. As a result, most households favored the convenience and affordability of chamber pots. Men usually relieved themselves in a cloakroom somewhere near the entrance hall, where a chamber pot was available. In Georgian times and in the early years of the new century, it was not uncommon for men to use a pot in a screened corner of a smoking or billiard room, but only in the company of other men.

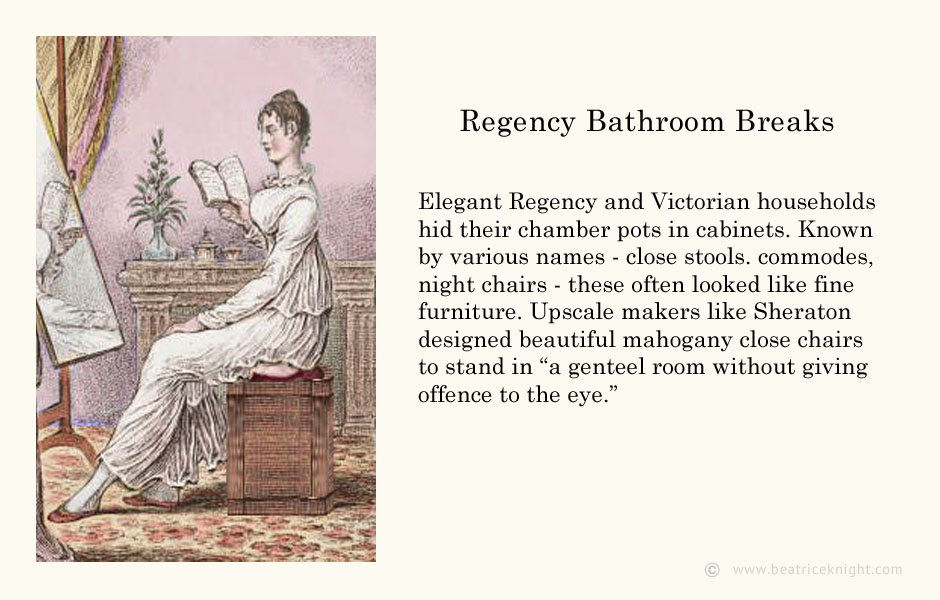

Close Stool

A retiring room with a washstand and commode was available for female guests. There, a maid in attendance provided any service needed and emptied the chamber pot each time it was used. Elegant Regency and Victorian households hid their chamber pots in cabinets. The most popular of these were lidded “close stools” that enabled the user to sit comfortably instead of squatting over the pot. High-end furniture maker Sheraton advertised a close stool (also known as a night chair) that could stand in “a genteel room without giving offence to the eye.” Inexpensive night chairs were also found in servants’ quarters.

In a well-run household, chamber pots were not lugged about in sight of family and visitors. Maids would enter a bedroom with a bucket of fresh water and a covered slop pail, empty the pot into the pail, rinse it out and return it to its cupboard or close stool. After all the pots were serviced, she would go downstairs and empty the pail into a slop sink that drained to an outdoor cesspit. If the house did not have one – usually located in a room called a maids’ closet – she would leave the pail out for the next night soil collection.

Slop Pail

Some Regency homes offered a type of dry toilet, a precursor to Moule’s earth closet invention later in the century. More common in rural areas, these usually comprised a wooden bench seat, under which a large pail was positioned. Earth and ash were sprinkled over waste to reduce odor, and as the pails filled they were emptied by servants or sent out for the night-soil men who carted waste to the market gardens surrounding most cities.

Modern-style flush toilets were not completely unknown during the Regency, and wealthy people with valve closets gradually upgraded. The first patent for a flush toilet had been issued in 1775 to Alexander Cumming. His design incorporated an S-shaped pipe below the toilet bowl, using water to seal off sewer gas. His design was extremely costly to make and install, so only the very wealthy bothered. Before Cumming, Sir John Harington had tried to solve the privy problem in 1596. He invented the first modern flushable toilet and installed a working prototype for Queen Elizabeth I at Richmond Palace. His concept was dismissed as crackpot, not least because 7.5 gallons of water was needed for the cistern – highly impractical when water had to be hauled by the pail.

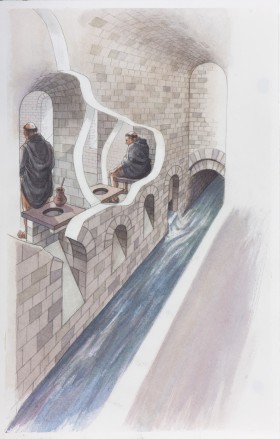

Going back in time, the Romans had excellent sewerage systems but took their know-how with them when they departed England around 400AD. Centuries later, English monasteries built multi-cubicle toilet blocks like the 11th century example at Lewes Priory (left), which incorporated a sewer where waste was discharged from chutes.

Going back in time, the Romans had excellent sewerage systems but took their know-how with them when they departed England around 400AD. Centuries later, English monasteries built multi-cubicle toilet blocks like the 11th century example at Lewes Priory (left), which incorporated a sewer where waste was discharged from chutes.

A down-market version of this concept was the communal pail closet or multi-seat “privy midden” (built over a cesspit) which served as public restrooms. Cesspits were emptied at night by “rakers” paid about ten times the usual workman’s wage for a job no one was eager to do. Privy middens were also built over running water where this was an option. The poorest in society relieved themselves in alleyways or watercourses.

Outhouses were a way of life for working people. In towns, these were usually enclosed “pail closets” located in the back yard. A receptacle was placed beneath a seat and emptied as needed.

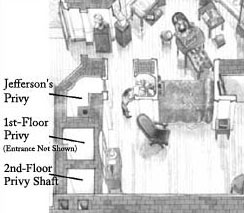

Jefferson’s Privies Floor Plan

By contrast, many French homes had relatively modern indoor sanitation before the Revolution. While in Paris from 1784 to 1789, Thomas Jefferson rented a townhouse with flush toilets. He was so smitten by “French manners” around hygiene that he built several “air closets” at Monticello. It’s anyone’s guess how their elaborate ventilation and waste systems worked. Demolition and conversion to heating and air-con vents destroyed the original functionality.

By the end of the Regency era , most middle-class Londoners were installing water closets. These discharged untreated sewage directly into rainwater drains and out into the Thames, the source of the city’s drinking water. The result was inevitable. In the hot summer of 1858, the Thames was effectively “dead” and the “Great Stink” overtook London. Along with the unbearable stench came an outbreak of waterborne cholera and typhoid fever. Parliament was forced to close but not before its members, finally affected by their own procrastination, rushed a bill into law funding a new sewer system. Undertaken by civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette, the colossal project would take almost 20 years to complete.

Sources

Eveleigh, David. Privies and Water Closets. Oxford: Shire, 2008.

Ragland, Johnny. The Hidden Room. Kingston University, 2004

The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia

Wilson, Alan. Comfort, Pleasure and Prestige: Country-house Technology in West Wales 1750-1930: Troubador, 2016