Mrs. Gill was one of the leading modistes of the Regency, and pioneered the design of white wedding dresses at a time when few women of fashion wore them. She was also deeply involved in charity work for the Asylum of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, along with her husband David.

Mrs. Eliza Gill 1781-1856

1807-1820: 1 Cork St., Burlington Gardens.

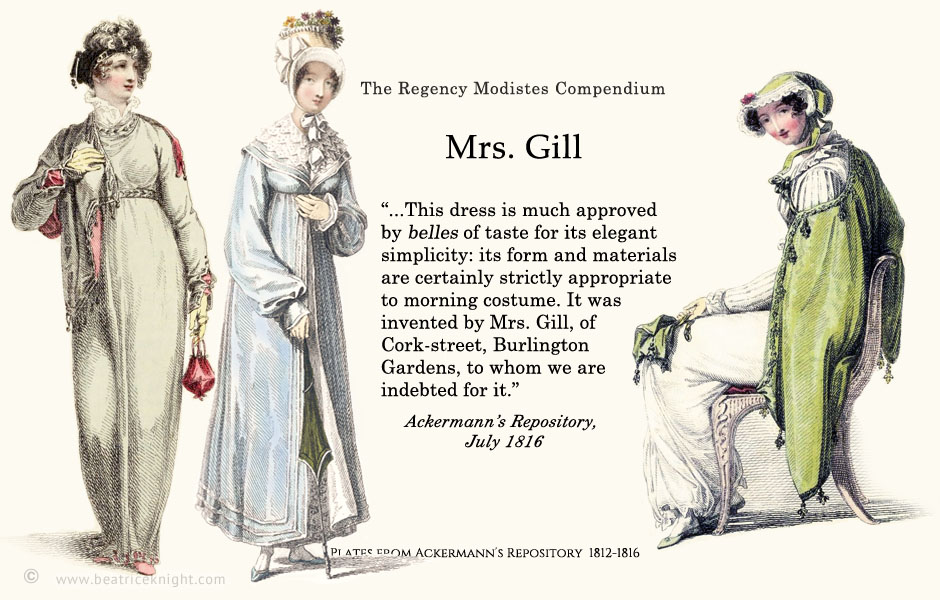

Unlike many of her counterparts, Mrs. Gill did not take out newspaper advertisements notifying “The Nobility and Gentry” of her latest gowns. She built her name as a modiste largely through word of mouth and reliability and rose, as described in Ackermann’s (1812), as “unrivalled” in creating genteel, elegant gowns.

Born Eliza Parker, she is thought by some to have been apprenticed for period to Madame Lanchester before that famed modiste went bankrupt for the final time. Mrs. Gill ran her business from the home she shared in Cork Street with her husband David, and their children. The couple were married in February 1803, at St. George’s, Hanover Square and had seven children. Their first daughter Eliza was born late in 1803, and a second girl followed a year later, Suzette (1804-1881). Tragedy marred their family life. Their third child, Emma, was born in May 1807 and died at age 4 years in November 1811, just two months after her sister Rosa (b. Sept 1811), was born. Their first son Edward was born just a year later, in December 1812, but died at the age of 13 months. Other children were Agnes (b.1808) and Albert (1816-1894).

Ackermann’s Repository, November 1811. Restored and retinted by Beatrice Knight.

During her family upheavals and heartbreak, Mrs. Gill threw herself into her business, building a reputation as a fine dressmaker. With the security of a husband whose occupation was described in his children’s baptism records as ‘gentleman’ and who later became a prosperous lace merchant, Mrs. Gill would have had domestic help to run her household and care for her children. It seems likely that she established her own business in 1807, featuring her earliest designs in Le Beau Monde in May of that year and continuing to promote her fashions sporadically until finally making the pages of Ackermann’s Repository, in 1811.

Questions about originality were raised by a design attributed to her in the November, 1811 issue of Ackermann’s. The carriage dress (left) clearly knocked off a pre-war French plate from 1802 (left, lower). The illustrations are so similar – far beyond simply featuring a pelisse that is an obvious copy – that the plagiarism may not be entirely that of Mrs. Gill. It seems possible that, for some reason, Rudolph Ackermann had his engraver work up the image and then attributed the design to Mrs. Gill.

What could have necessitated this? Real life paints a picture. Mrs. Gill was heavily pregnant in July/August of 1811, and perhaps she was running late in suppling the sketches for promotion space reserved in the November issue. She gave birth in September, and in November, her four-year-old son died. Work was probably the last thing on her mind. Perhaps Ackermann had to improvise at the last minute. It’s also possible that, finding herself in a pickle over a looming deadline, Mrs. Gill decided to copy a long-forgotten plate from pre-war French magazine dating back almost a decade. That in itself, suggests extenuating circumstances. English fashion magazines replicated French plates on occasion, however they chose current designs and waited only a month or two before publishing them.

Douillette or cosy mantle. Journal des Dames et des Modes. December 1802. Image courtesy of Bibliotheque Nationale de France

Whatever the explanation, Mrs. Gill never repeated this aberration, as far as I can ascertain. In the years that followed, she created clothing that was reliably tasteful and exclusive-looking, and which consistently reflected her sensibility. She dressed clients from both fashionable high society and the emerging nouveau riche, and carved out a special distinction for herself with her wedding dress designs.

White wedding dresses had their kickstart during the Regency era, and Mrs. Gill was the first “name” modiste to promote the idea in a fashion plate. Princess Charlotte had just married Prince Leopold wearing the usual elaborate wedding dress expected of royal and beau monde brides. Made by Mrs. Triaud of Bolton St. the princess’s dress was: “…composed of a most magnificent silver lama over a rich silver tissue slip with a superb border of silver lama…”

White wedding dresses had their kickstart during the Regency era, and Mrs. Gill was the first “name” modiste to promote the idea in a fashion plate. Princess Charlotte had just married Prince Leopold wearing the usual elaborate wedding dress expected of royal and beau monde brides. Made by Mrs. Triaud of Bolton St. the princess’s dress was: “…composed of a most magnificent silver lama over a rich silver tissue slip with a superb border of silver lama…”

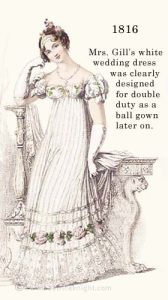

It would have taken some chutzpah to promote a simple white wedding dress directly after that example, but Mrs. Gill had her finger on the pulse. In 1816, English women were having their first Season without a war in years! They wanted beauty, joy, freshness, and perhaps a return to innocence. The Romantic era was about to explode. It’s no accident that this reputedly empathetic, sweet-natured modiste created a beautiful, romantic bridal gown for “a young lady of high distinction” (right) Ackermann’s published the design with this description:

“A frock of striped French gauze over a white satin slip; the bottom of the frock is superbly trimmed with a deep flounce of Brussels lace, which is surmounted by a single tuck of byas white satin and a wreath of roses; above the wreath are two tucks of byas white satin. We refer our readers to our print foe the form of the body and sleeve: it is singularly novel and tasteful, but we are forbidden either to describe it, or to mention the materials of which it is composed.”

Mrs. Gill nailed it, and before long every upscale modiste was making white wedding dresses.

Mrs. Gill’s Sensibility – Tasteful, Genteel and Sometimes “Uncommonly Novel”

Mrs. Gill’s Sensibility – Tasteful, Genteel and Sometimes “Uncommonly Novel”

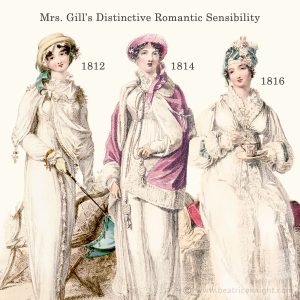

Mrs. Gill created fashions women found easy to wear, but which also had “lady of quality” stamped all over them. Of all the London modistes in the early 1810s, her styles most consistently embodied the Romantic sensibility that emerged in English fashion during the war with Napoleon.

Travel to Paris was impossible in those years, so Englishwomen had little idea what their French counterparts were doing. Modistes like Mrs. Gill evolved a look that was distinctively British, referencing patriotic themes, historic eras, and a poetic feel. At a time when many women’s gowns left little to the imagination, with revealing flimsy muslin skirts and extensive décolletage, she opted for layers, lace, pelisses, and pelerines. I get the impression that she created the kind of clothing she would wear, herself.

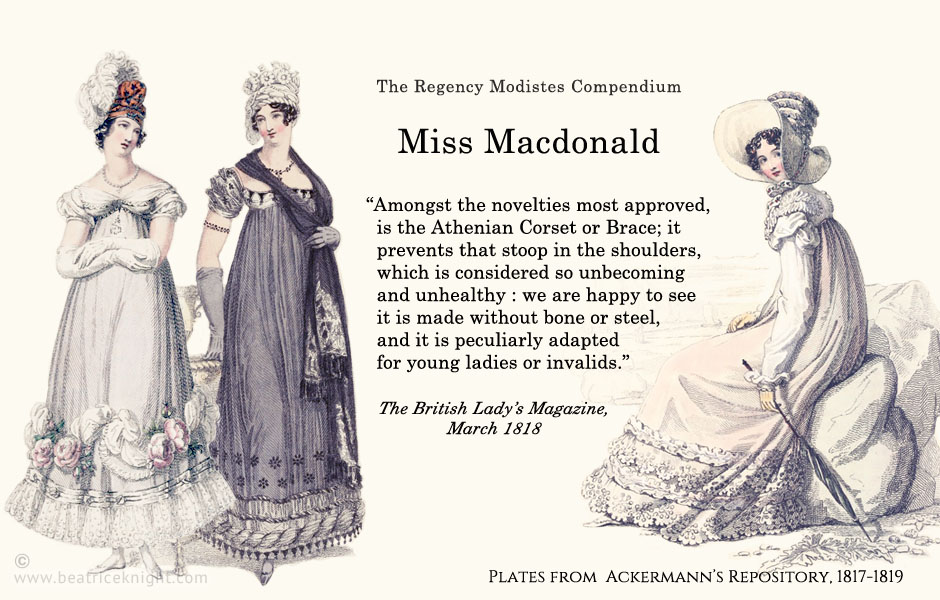

The dresses above appeared in Ackermann’s Repository between 1812 to 1816. They illustrate the “chaste” feminine attire she was known for. The 1814 walking dress was the closest she came to a military theme, featuring a “.. Cossack mantle of pale ruby or blossom-coloured velvet…”

After the war ended in 1815, luxury French fabrics and trims were at last attainable again. Englishwomen were eager to flaunt both their victory and their increasing prosperity. Fashions became more elaborate and fussy. Mrs. Gill had always been inclined toward some whimsical looks; the carriage dress (right) certainly leaves no stone unturned. Ackermann’s (March, 1816) diplomatically hailed the design as “original and elegantly fancied.”

After the war ended in 1815, luxury French fabrics and trims were at last attainable again. Englishwomen were eager to flaunt both their victory and their increasing prosperity. Fashions became more elaborate and fussy. Mrs. Gill had always been inclined toward some whimsical looks; the carriage dress (right) certainly leaves no stone unturned. Ackermann’s (March, 1816) diplomatically hailed the design as “original and elegantly fancied.”

Mrs. Gill, having the support of a solid middle-class husband of means, never struggled with the financial challenges faced by some of her rivals. In 1818, Mrs. Gill was among the preferred designers for elegant society picnic dresses, referenced in several guides. She and her husband were known philanthropists and she was still active in her charity work in 1821, according to records of subscribers and officers of the Asylum of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor.

Mrs. Gill was listed in the Pigot & Co business directory, 1822, as still operating from Cork Street. However, she seemed to have stopped promoting her designs in fashion magazines by then. Having dominated the pages of Ackermann’s Repository through 1816, she did not purchase promotion spots for 1817. No modiste was credited for the fashion plates in that publication until June 1817, when two of Mrs. Marchant’s fashions were featured. Her son, Albert started at Eton College in 1823. Mrs. Gill turned 42 that year. Perhaps she stepped back from her business and allowed it to simply peter out. Being financially comfortable, she could make that choice.

Mrs. Gill died in London, aged 75, on 3 October, 1856. Her husband David had pre-deceased her in April 1839.

Read More

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. London. R. Ackermann.