Natural Beauty – the Regency Aesthetic

As the 19th century dawned, no one wanted to look like Marie Antoinette. In a backlash against the powder, patch and paint of the decadent 1800s, the Regency beauty ideal for women of the privileged classes was natural. Unless you were married, the smallest hint of rouge was tantamount to declaring yourself a fallen woman. But the change in aesthetic was not only a matter of taste.

With the gruesome excesses of the French Revolution fresh in everyone’s minds, the English upper classes worried that they, too, could find themselves on the chopping block if revolutionary fervor infected the lower orders. Women adopted pastoral simplicity and plain fabrics. Natural beauty was the order of the day, unaided by cosmetic art. This mindset swept Europe.

The Backdrop

Some five years earlier, as the Terror tightened its grip on France, the Revolution began to implode. The so-called Committee of Public Safety had consolidated power within the National Convention (the French parliament) and set about purging rival factions. They threw their opponents in prison, passed decrees to extinguished their right to due process, and implemented the Terror as state policy, with the aim of silencing and eliminating dissent. Anyone who disagreed with Committee strongman Maximilien Robespierre was pronounced an enemy of the Revolution; execution typically followed. In July 1794, Robespierre was planning yet another bloody purge to take down his political opponents. Instead, they staged a coup and sent him and his fanatical cohorts to the guillotine.

After Robespierre’s execution, the Terror ended and the revolutionary administration formed the French Directory and established a constitution. By then, the Revolution had sunk France into chaos, paranoia, butchery, and economic disaster. Inflation and food shortages were unending. Jacobin and royalist uprisings unsettled the country. And France was also at war with Britain and Europe, in an effort to expand international boundaries.

Man of the Hour

Amidst rising public discontent, France was ripe for new leadership and the man of the hour was military hero Napoléon Bonaparte, a minor Corsican aristocrat whose victories in Egypt and Italy inspired the French public to dream of glory and “empire.” Riding a wave of popularity, he elected himself Consul for life in 1802 and stabilized the country. Two years later, cooking up an imaginary royalist plot as justification, he anointed himself emperor and created a new aristocracy made up of his relatives and supporters.

This new Empire society was led by his wife Josephine, whose personal style paid homage to the classical styles of ancient Greece. By means of his Civil Code (1804), Napoléon imposed his personal taste on women’s fashion, legislating what they should wear. He also set out to restore the market for luxury goods as part of rebuilding the French economy. The nouveau riche French elite were encouraged to flaunt their wealth, and Empress Josephine and French socialites like Juliette Récamier (left) became the leading influencers of the day.

This new Empire society was led by his wife Josephine, whose personal style paid homage to the classical styles of ancient Greece. By means of his Civil Code (1804), Napoléon imposed his personal taste on women’s fashion, legislating what they should wear. He also set out to restore the market for luxury goods as part of rebuilding the French economy. The nouveau riche French elite were encouraged to flaunt their wealth, and Empress Josephine and French socialites like Juliette Récamier (left) became the leading influencers of the day.

Natural Beauty

The beauty ideal that defined the early 19th century woman was a pale, velvet-soft complexion with a delicate hint of roses in the cheeks and soft red lips, all attributed to the gifts of nature and the ladylike virtues of temperance and cleanliness. To achieve the coveted natural glow, appropriate pursuits were encouraged – riding in the park, promenades, dancing and pianoforte. If a young woman had been overlooked by Nature, or had the misfortune to have skin pitted by smallpox, she had no choice but to use cosmetics and skincare preparations.

To an elegant Regency woman, nothing proclaimed lower class origins like blemishes, freckles, or a tan.

In Pride and Prejudice, jealous Miss Bingley is eager to point out Elizabeth Bennet’s shortcomings, observing: “How very ill Miss Eliza Bennet looks this morning, Mr. Darcy. … She is grown so brown and coarse! ”

In Alverstone, Lady Winford is despondent over her younger daughter Rose and their newly arrived American cousin: “It cannot be helped that you want for Charlotte’s brilliant complexion. And poor Sylvie looks positively swarthy. The American sunshine is ruinous, I suppose. Let her try your Balm of Mecca.”

Balm of Mecca (better known as Balm of Gilead) was one of the most desirable ingredients used in the preparation of skincare products (known as “cosmetics” back then) intended to even out tone and whiten freckles (sun-bran). Sold also under other exotic-sounding names like white balm of Constantinople and balm of Egypt, it was a rare, costly pale sap expressed by slicing the bark of balsam trees (called beshem) that still grow wild today in the valley of Mecca. Those trees are thought to be strains descended from the most prized trees of the ancient world – the bosem that grew in Judea 2000 years earlier.

According to historian Josephus, the Queen of Sheba brought an “abundance of bosem” to Jerusalem among many gifts for King Solomon some 3000 years ago. The Jews loved the exotic oil and set about cultivating the trees that produced it. As far back as the Second Temple period, records mention terraced balsam orchards around the Dead Sea. The most expensive spice of ancient times, praised by Pliny the Younger and other famed Greek and Roman writers, balm of Gilead was used as a sacred oil in Jewish temples.

After Titus captured Judea in 70 AD, balsam became a major export revenue earner for the Romans . The Jews had burned the orchards to prevent the trees from falling into the Roman occupiers’ hands, but were unsuccessful. The original balsam terraces can still be seen in the hills of Ein-Gedi nowadays, along with the ovens used to make the balm. For the past decade, Israel has been trying to re-establish the trees at their original site, hoping to create a 21st century version of the oil.

The Duties of a Lady’s Maid devotes several pages to the benefits of “balm of Mecca” in bestowing brilliance to the complexion, warning readers about imitations that sell for a mere 25-35 shillings and noting that the same quantity of the real thing “cannot be procured under four guineas.” It was usually mixed with barley water or almond milk and applied rather like an exfoliating mask. Some women left it on overnight. Its citrus scent probably made it more agreeable than another popular mask made of onion water, white lily and Narbonne honey mixed with white wax. Natural exfoliating masks were as big then as they are now. Regency women used cucumber, strawberries, oats, honey and fermented milk just as many of today’s brands claim.

Cosmetics to Die For

While it was perfectly ladylike to soften and refine skin, “paint” was strictly for bits o’ muslin, the type of women not received in polite society. To get around the unspoken ban on rouge and lip pomatum, ladies of the haut ton could claim to be unwell. Delicate health was virtually a distinction in itself, and those afflicted had a dispensation for all manner of cosmetics, either to bestow a healthy bloom or make them look “pale and interesting.”

For those who favored a consumptive pallor, there was nothing like white lead. Toxic and dangerous…yes. But nowadays, women think nothing of being injected with Botox, a neurotoxin secreted by the botulism bacteria. It’s not surprising that our Regency era counterparts also took risks to look young and beautiful.

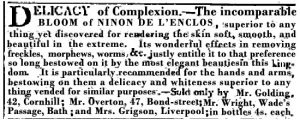

Bloom of Ninon de L’Enclos, a lead-based skin cream made of white lead, almond oil and lavender, left such a trail of ill-effects and even death that the Monthly Gazette warned in 1819: “…instead of animating the countenance, (using white lead products) would assuredly, by paralyzing the nerves, render it inanimate.”

By that time magazines, doctors and ladies maids had been warning against the use of white lead for at least fifty years, but that did not prevent advertisements like the one seen in The Times in 1805 (left).

By that time magazines, doctors and ladies maids had been warning against the use of white lead for at least fifty years, but that did not prevent advertisements like the one seen in The Times in 1805 (left).

White lead was used in a wide range of other commercial skin creams. The best known and most affordable was probably Gowland’s lotion, advertised in 1809 at 2s 3d. With its base of mercuric chloride, derived from sulphuric acid, or superacetate of lead (as described in The Modern Practice of Physic), it was a popular treatment lotion for pimples but “by no means safe” according to Thomas Graham (Modern Domestic Medicine).

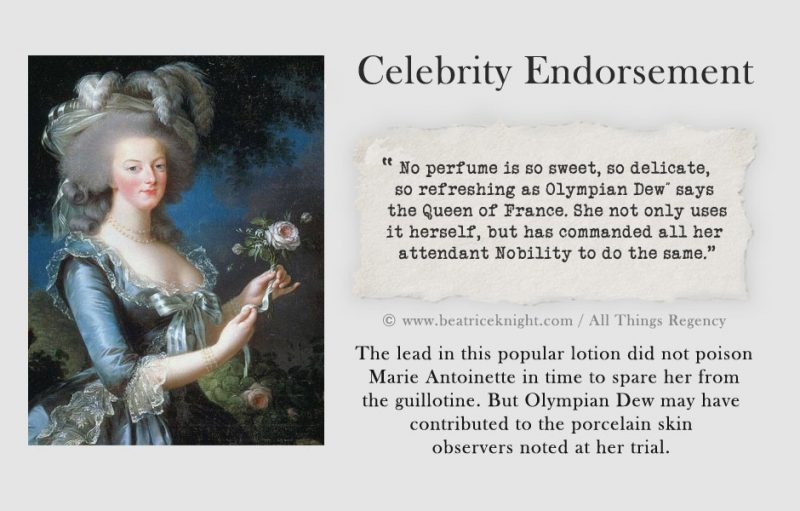

A competing product, Olympian Dew, also known as Grecian Bloom, had been widely advertised since the late 18th century, along with claims of celebrity endorsement by Queen Marie Antoinette of France. At 4s 6d a bottle, but costing little more than a penny to make, it was an extremely profitable beauty product stocked by perfumers all over England.

Red lead, vermilion, bismuth, sulfur and mercury were found in many a rouge pot, and health-conscious beauty experts of the era recommended women make their own blush from safer vegetable extracts like safflower. Commercial cochineal-based products like the upscale Portuguese Rouge, sold in pretty pots, were a favorite of discriminating ladies. Its London knock-off was safflower-based and less pricey, as was Spanish Wool (made by London Jews) and Spanish Papers (from China).

A foundation made with Briancon chalk (white talc) and vinegar was applied with a hare’s foot and damp fingers, and was safe compared to white lead- and tin-based paints, which were not only toxic but could make the skin look gray.

Women tinkered with early versions of eye-liner and kohl, usually made with lead sulfide, and covertly tinted eyelashes and eyebrows with elderberry extract. Frequent use of belladonna (deadly nightshade) drops in the eyes could kill, but at least one would have seductive dilated pupils.

Women who preferred not to poison themselves had their own recipes for benign cosmetics and washes, like Denmark Lotion and Milk of Roses, usually made by the housekeeper or ladies maid. Most prosperous Regency households had a distillery room where everything from soap to medicinal remedies was produced.

Women who preferred not to poison themselves had their own recipes for benign cosmetics and washes, like Denmark Lotion and Milk of Roses, usually made by the housekeeper or ladies maid. Most prosperous Regency households had a distillery room where everything from soap to medicinal remedies was produced.

I’m currently creating a compendium of original formulas from an ancestor of mine, Louise (left), who turned lotions and potions into a small business with her housekeeper, using old family still-room recipes dating from 1790-1840. I have many of her recipes in old diaries my grandmother handed down to me (Louise being her great-great grandmother).

Sources and More Reading

Downing, Sarah Jane. Beauty and Cosmetics 1550-1950. Shire Library, 2012.

Grimble, Frances. The Ladies Stratagem. San Francisco. Lavolta Press, 2009.

Thomas, Robert. The Modern Practice of Physic. London, 1813.