Mourning customs have differed widely between societies and classes throughout history. Because mourning was very strictly observed in Victorian England, there seems to be less awareness of the somewhat looser conventions that prevailed during the Regency years.

Regency Mourning

In the early 1800s, life was short. War with Napoleon left no village untouched by battlefield losses, and the mortality rate for children was painfully high. This reality has always been poignant for me, personally, as I have a miniature of a female ancestor who had thirteen children between 1804-1820. Only three reached adulthood. I think of her, constantly pregnant while still in mourning for another of her dead children. Many women shared her experiences at the time. And without grief counselling.

In a way, mourning was their form of therapy, a public statement of their sorrow, which set them apart and enabled their grief to be validated and supported. Some general guidelines determined mourning periods, attire, and social activities based on a person’s relationship to the deceased: the closer the connection, the longer the mourning period.

Mourning Periods

| Relationship | Mourning Period | Full/Half Mourning |

|---|---|---|

| Spouse | 1 year | 6 mth/6 mth |

| Child | 1 year or 3-6 months for infant | by discretion |

| Parents/In-Laws | 6 months | 3 mth/3mth |

| Grandparent | 6 months | 3 mth/3mth |

| Sibling/In-law | 3 months / 6 weeks | 1 mth/2 mth/or by discretion |

| Aunt/Uncle | 3 months or less | 1 mth/2 mth/or by discretion |

| First Cousin | 2-3 weeks | Half |

| Second Cousin | 1 week | Half |

| Close Friend | 2 weeks | Half |

| Public Figure | Designated by Court | Designated by Court |

Full Mourning

Half Mourning

Personal Discretion

Because family members were not uniformly close or beloved, Regency mourners exercised some personal discretion. Families were usually guided by a female “enforcer,” who was most au fait with the family tree. This grandmother, maiden aunt or whomever would set the mourning period and appropriate attire. As the mourning phases progressed, she would remind family members when they could make the switch to half-mourning and advise on any issues of etiquette around outings and dancing. It was not unknown for the “mourning czar” of a family to lower the bar for relations held in poor regard, reducing full mourning to half the customary period, or forgoing that phase entirely – why drag out the serious black bombazine and creped bonnets for the undeserving?

When children died, the older the child the longer their mother would spend in full mourning, as a rule. An only child was often mourned for a longer period. No one would criticize bereft parents for making their own choices after losing a child. Some women, especially those who lost an only child, after making the switch to half-mourning, elected to remain in shades of lavender, lilac and grey for the rest of their lives.

Widows and Widowers

Unsurprisingly, a double standard existed between men and women. Widows were held to a rigid code of conduct after losing a husband, and faced censure if they departed from the usual traditions, such as not attending public events while in full-mourning. A widow who remarried before her husband had been deceased for a year was treated as a pariah by polite society. Men, however, were granted more latitude. They were usually obliged to exist more in the public sphere, and were not expected to forgo all forms of entertainment. Provided they did not marry until at least a year and a day after their wife’s demise they could return to most activities within a few months.

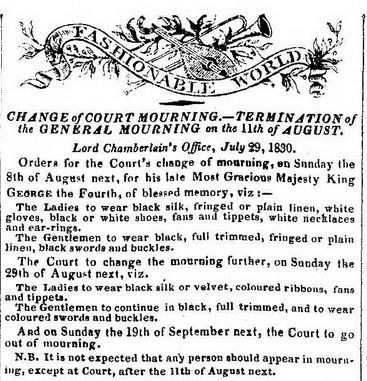

Court Mourning

In addition to personal mourning for loved ones lost, “court mourning” proclamations set the guidelines for mourning royals and public figures. In general, working people did not have the time, money, or inclination to follow these edicts unless the departed was top tier: kings, queens, heirs to the throne. But some royals were more popular than others, just as they are today. When Princess Amelia died on November 2, 1810, she was mourned by people of all classes. Her father King George III was so grief-stricken, he relapsed into derangement from which he would never recover, leading just three months later to the installation of his eldest son as Prince Regent.

In addition to personal mourning for loved ones lost, “court mourning” proclamations set the guidelines for mourning royals and public figures. In general, working people did not have the time, money, or inclination to follow these edicts unless the departed was top tier: kings, queens, heirs to the throne. But some royals were more popular than others, just as they are today. When Princess Amelia died on November 2, 1810, she was mourned by people of all classes. Her father King George III was so grief-stricken, he relapsed into derangement from which he would never recover, leading just three months later to the installation of his eldest son as Prince Regent.

Most often, however, the only people who dutifully heeded every court mourning decree were the beau monde. Let’s face it, they had nothing else to do, and could not pass up the chance to be seen in desperately fashionable mourning attire? Call it virtue signaling, Regency style. Between 1800-1830, there was ample opportunity.

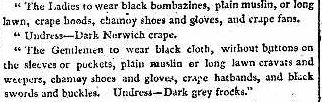

When King George IV, the universally-detested former Prince Regent, naturally full mourning was decreed. The Morning Post published the notice (left) setting the guidelines for courtiers and fashionable people.

Slight Mourning

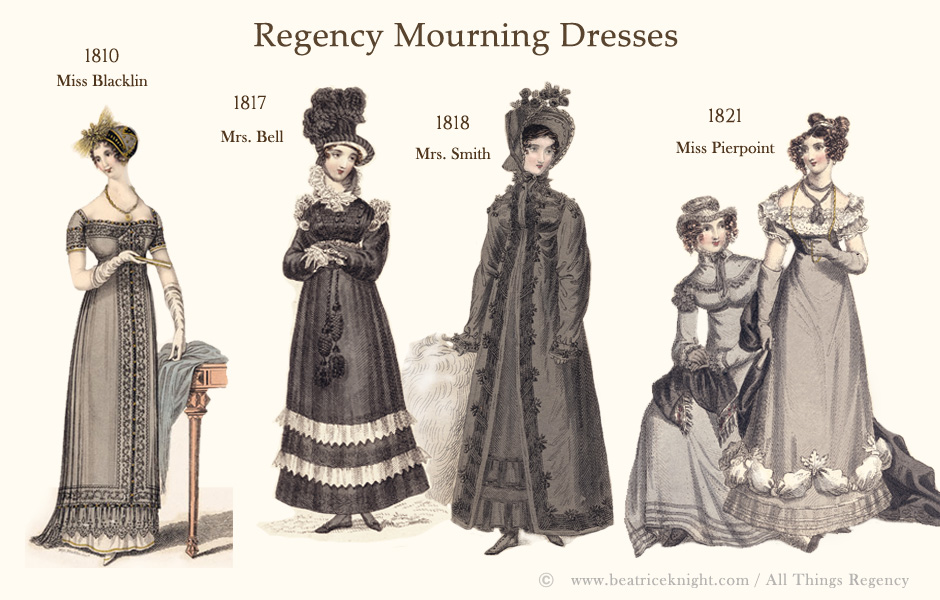

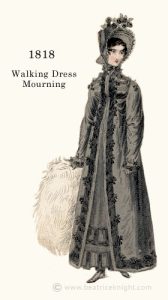

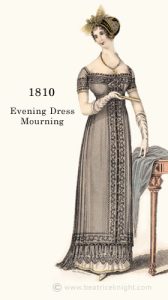

Regency mourning dress involved two stages. The first was full or deep mourning, which required dresses in black fabric such as bombazine or crepe/crape, which had a dull appearance, teamed with black accessories, and ‘craped’ head-wear. When the full mourning period ended, half-mourning attire was worn – usually dresses in shades of grey, lilac or lavender; with some white, such as blond lace at the wrist and neckline.

Between full- and half-mourning, some people adopted a transition phase known as ordinary or slight mourning. Black fabrics were still de rigueur, but fabrics were allowed to have a little more sheen, and a tasteful amount of white trim was allowed. Mrs. Bell’s 1817 dress in the main post image illustrates “slight mourning.”

The Big One

Regency England saw one public mourning event that eclipsed all others, before or since. On November 6, 1817 , Princess Charlotte of Wales, died at only 21, after delivering a stillborn son. This tragedy plunged the nation into a frenzy of grief not seen again until the public outpouring for Princess Diana 180 years later. Charlotte’s excruciating 50-hour labor and its outcome were so traumatic that the royal obstetrician, Sir Richard Croft committed suicide within a few months. Prince Leopold, Charlotte’s husband, suffered some type of depression for the rest of his life; from all accounts they were passionately in love.

Princess Charlotte was destined to be the next queen and her baby boy would have been king after her. The double loss struck a blow to the public psyche unprecedented in British history at the time. Academic papers on the actual cause of the princess’s death and how she might have been saved are being published to this day, two hundred years later.

One met in the streets people of every class in tears, the churches full at all hours, the shops shut for a fortnight, and everyone, from the highest to the lowest, in a state of despair which it is impossible to describe. — Dorothea Lieven, socialite wife of the Russian ambassador

The princess was cherished and extremely popular, not least because her father, the erstwhile Prince Regent, was universally loathed. The calamity not only touched people deeply, it threatened the succession and nearly brought down the monarchy. It also carved a path to the throne for young princess Victoria. But that’s another post.

The Lord Chamberlain’s Office sent out notices the next day, decreeing the attire for official court mourning (London Star, left) and notifying a General Mourning, for which “…all persons do put themselves into decent Mourning…” beginning on Sunday, November 9. The nation, in dazed disbelief, had already come to a screeching halt and would would remain entirely shut down the next two weeks. Every entertainment was cancelled. Mourning black fabrics sold out overnight. Beggars dyed rags for armbands. Anyone not seen in mourning risked being publicly booed, even assaulted. Advertisements for black mantles, jet jewelry, black stockings and gloves filled the newspapers. Sales of colorful textiles and trims collapsed to such a sustained degree; desperate manufacturers petitioned the government to end the mourning period more quickly lest they went bankrupt. The few fashionables seen walking were “…wrapped in black cloth shawls which have a broad binding in crape.” The majority simply stayed home in morning garb complete with a mourning ruff and “weepers” (wide white cuffs) of thin long lawn.

The few fashionables seen walking were “…wrapped in black cloth shawls which have a broad binding in crape.” The majority simply stayed home in morning garb complete with a mourning ruff and “weepers” (wide white cuffs) of thin long lawn.

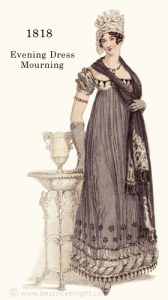

It was not all for show. In the months following the princess’s death, doctors reported an uptick in heart failure, nervous conditions, and suicide. Yet, despite deep mourning, evening dresses flaunted expanses of naked flesh. Two months into the mourning period, Ackermann’s featured the fashion plate (left), a design by Miss McDonald of Wells St.

The official court mourning ended on Jan 31, 1818 and fashion magazines published the fashion plates carried over from the past three months. But there remained little appetite for gay fashions

Read More

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. Garland, 1989.

Trumbach, Randolph. The Rise of the Egalitarian Family. Academic Press, 1978