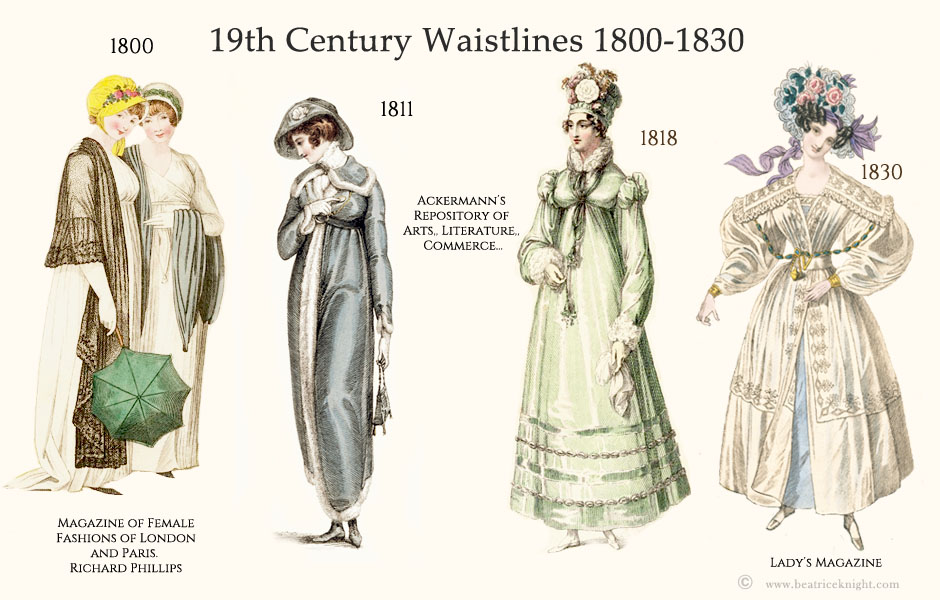

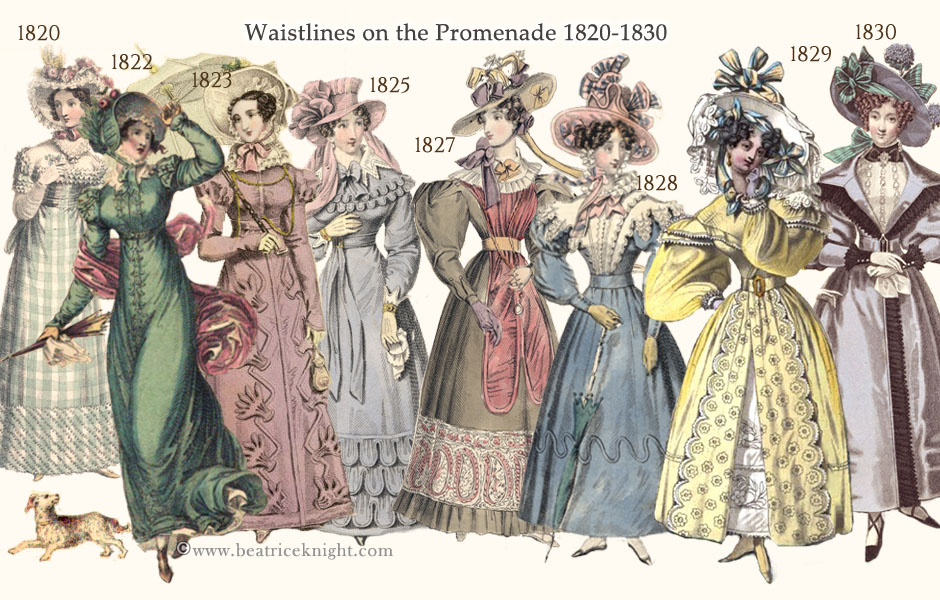

Empire waists epitomized Regency England, but change was underway when the Prince Regent finally took the throne as King George IV in 1820. The broader Regency era would last until his death in 1830, and the ten years of his rule would witness some of the most dramatic shifts in the history of women’s fashion.

Regency Waistlines Part Three 1820-1830

The 1820s was a decade of transition that would sweep away the Empire waist and neo-classical styles women had been wearing since the late 1790s. It did not happen overnight.

1820 was a good year for England. There was a new king on the throne, the British navy ruled the waves, and since beating Napoleon in 1815, the nation had entered a period of industrial growth and exploding prosperity.

With trade back to normal in the post-war era, draperies like Mr. Hill’s Parisian Depot in Regent Street stocked up on luxurious French fabrics, targeting prosperous middle-class customers hoping to carve out a place among the beau monde. Not that it would help; no one of rank would socialize with “mushrooms” who had the “smell of shop” about them. Social hierarchy was rigidly enforced, with upper crust women as gatekeepers. No sooner was some accessory or hat trim seen everywhere than it was abandoned as “common” by ladies of the first stare.

English fashion had focused inward during the war with Napoleon, and had forged its own distinctive identity. By 1820 the Romantic movement dominated English culture. Fascination for the past and pride in English heritage and power were central themes in women’s clothing.

English fashion had focused inward during the war with Napoleon, and had forged its own distinctive identity. By 1820 the Romantic movement dominated English culture. Fascination for the past and pride in English heritage and power were central themes in women’s clothing.

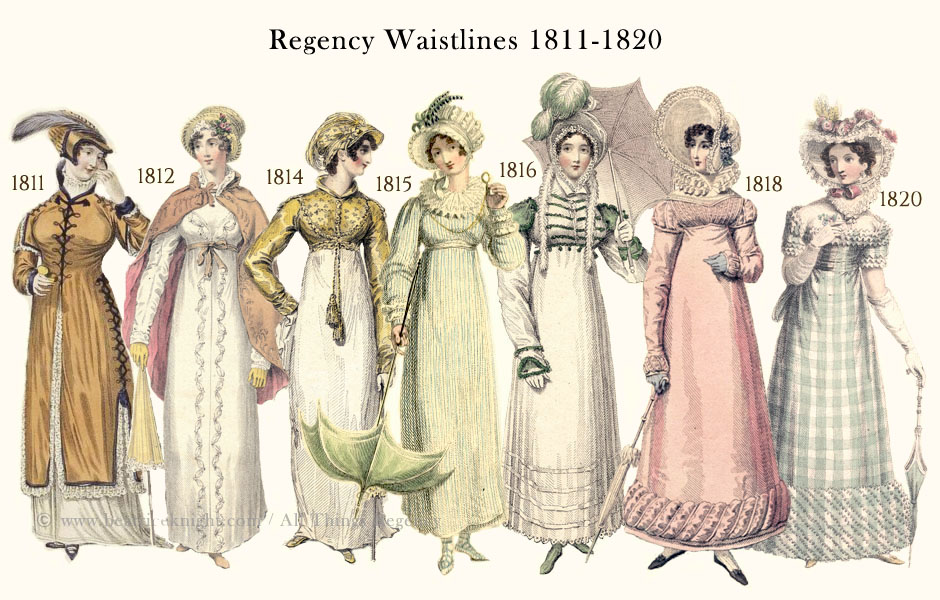

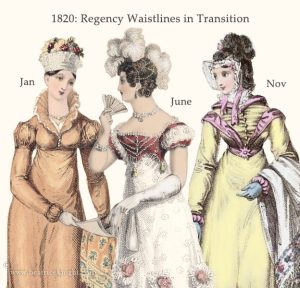

1820 marked a turning point for Regency waistlines

As the new decade began with a new monarch on the throne, a transition was about to sweep through Regency women’s fashion. 1819 had ended with high waists and business as usual, but English fashionistas had barely had time to order their gowns for the 1820 Season when longer waists suddenly appeared in fashion magazines.

The transition had its origins in Paris, where women had been wearing longer waists through most of 1819. But the death of King George III on 29 January 1820 marked the turning point for English waistlines. The nation launched into full mourning, which continued 19 March, when fashionable people switched to half-mourning. Ladies magazines abandoned their slated fashion plates until April, instead featuring mourning designs. Most had already printed their February issues by the time the king died, and had to hastily create supplements, featuring full mourning weeds.

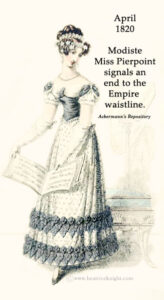

Ackermann’s Repository. April 1820.

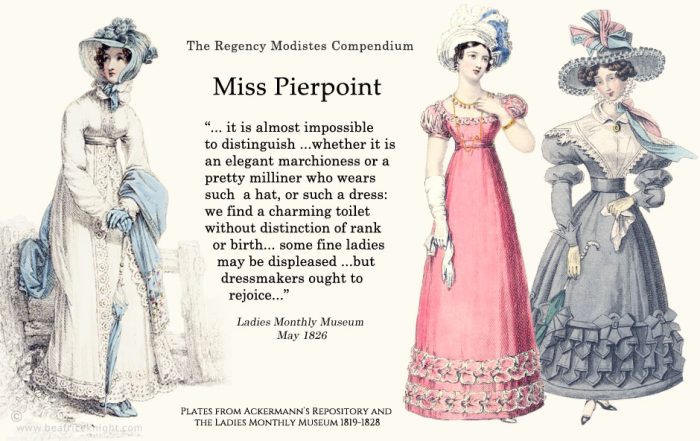

Miss Pierpoint, who would become London’s most influential modiste through the 1820s, seized her chance. Two of her mourning fashions for the late king were featured in the March issue of Ackermann’s Repository, where descriptions of both stated: “…the waist is rather long…” In April, she doubled down with an evening dress (left) for which “the waist is long, and it is a little, but very little, peaked in front...” That same month, in their “French Female Fashions” column, Ackermann’s mentioned that waistlines across the channel were “..very long…”

La Belle Assemblée had opened the year with plates of French fashions that featured long waists. However, their resident modiste and fashion editor, Mrs. Bell offered only a vague nod to the longer line in a full mourning walking costume with a medium high waist belted for emphasis. Later in the year, Mrs. Bell made a transition to longer waists from August onward. Her change of heart seemed to come about after aristocratic women broke with court dress tradition at the first Drawing Room held by the newly crowned King George IV in July.

La Belle Assemblée. July 1820.

The new king had announced an end to the anachronistic court dresses his mother had ordained throughout King George III’s reign, with hoops and silhouettes stuck in the past. Lady Worsley Holmes’s gown departed emphatically from Queen Charlotte’s edicts and made a statement about the present, signifying King George IV’s stamp of approval on a change in waistline.

While her dress still had a medium high waist, the design and trim made it seem longer and the skirt appeared to fall from a more natural waist. Lady Worsley Holmes’s gown was featured in La Belle Assemblée amidst hand-wringing that: “A beautiful drawing was taken of this superb and elegant dress last month, but our Engraver disappointed us of then offering it to the public…”

Leaked to the press for perusal by the great unwashed! How irksome.

In the same issue, fashion editor Mrs. Bell, roundly condemned the long waistlines and narrow hips favored by Parisian women: “…they still, with the help of whalebone and steel, contrive to press a part of their hips into the service of the waist, and waddle along as if their legs were no longer than those of a duck. This hideous waist must be displayed too when the weather is warm, at the promenade, by the adoption of only a black lace handkerchief shawl, or with a canezou stiffened with whalebone like their stays.”

Harsh words, from the same magazine that published fawning puff pieces on Paris fashions every month while the two countries were actually at war ! Inevitably, market reality caught up. A year after deploring the Parisian look, La Belle Assemblée featured Mrs. Bell’s the carriage dress (right) in July 1821, deeming it “an elegant costume” despite its overt similarity to the “hideous” Parisian costumes despised the previous year.

The Transition to Natural Waists Did Not Happen Overnight

Sensible Englishwomen were not about to replace their entire wardrobe just because the French had decided Empire waists were passé and fancy society women were leaping on the bandwagon.

A few “dashers” adopted the new look in their streetwear during 1820-21, but everyone else took a wait-and-see approach. After all, English women had seen this movie before. Ten years earlier, waistlines had lengthened briefly in 1809-1811, only to shoot back up higher than ever.

In relative terms, dresses were very expensive. A good quality walking dress and pelisse cost more than three month’s wages for a lady’s maid. Even middle class women only purchased a few new dresses each year. Such a big transition had to be managed without blowing their budgets, so favorite gowns were made over, spruced up with new trim, or handed down to younger sisters.

New dresses were purchased with longer waists, but waistlines remained a few stubborn inches above the natural waist. Attention focused on fabrics, trim, sleeves, ruffs, puffs, flounces, stomachers, turbans, and hats. Skirts became fuller, detailing more lavish, fabrics richer. La Belle Assemblée reported: “Never did we observe white dresses so little in favor; where we see silks of every color of the rainbow, we may safely say that one white dress appears only among fifty of the former.”

New dresses were purchased with longer waists, but waistlines remained a few stubborn inches above the natural waist. Attention focused on fabrics, trim, sleeves, ruffs, puffs, flounces, stomachers, turbans, and hats. Skirts became fuller, detailing more lavish, fabrics richer. La Belle Assemblée reported: “Never did we observe white dresses so little in favor; where we see silks of every color of the rainbow, we may safely say that one white dress appears only among fifty of the former.”

During the transition years, the Tudor sensibility of the neck and sleeves seen in the 1821 carriage dress was very much in vogue on London streets. The sleeves puffed at the shoulder foreshadowed a trend that would explode as the 1820s progressed.

In Paris, the gigot sleeve was beginning its fashion reign

Across the channel, cinched waists and loose full blouses with sleeves en gigot came into fashion in 1821. As ruthlessly as they’d guillotined opponents of the Revolution twenty-five years earlier, Parisians relegated Emperor Napoleon’s beloved Empire silhouette to the dustbin of fashion history. And, in a shock move, even for those brazen hussies in Paris, “…a good many élégantes have adopted the fashion of trowsers under the blouse…worn sufficiently short to display a little of the rich lace or worked flounce which finishes the trowsers.”

Fashion columnist, Eudocia, who wrote of this disgrace, went on to say: “…for the exhibition of paintings, or for dinner parties, no elegant woman will be seen in anything but a blouse. I need not describe to you the corsage of this dress for it is completely that of a waggoners frock…”

Eudocia thought English women had more sense than to copy their French counterparts: “…Some few élégantes have adopted the blouse, which is at present so fashionable in France, but it is by no means generally worn.” However, Englishwomen did not hold out for long against the dictates of Paris. The war was over, and the English middle class were spending more on fashion than ever. By September 1822, blouses had caught on in London, and Ackermann’s Repository told readers that “…the most fashionable morning dress is the blouse: it is made in cambric muslin, and trimmed with deep tucks or flounces.”.

Ackermann’s Repository, July 1825

The new silhouette offered the newly rich a chance to flaunt their wealth. There were no more simply-dressed Grecian sylphs floating about fashionable drawing rooms. Dresses were bigger, skirts fuller, fabrics richer, hats grander, and sleeves sillier than ever. By 1825, bodices were tight, corsets were indispensable, and no one would be caught dead in a high waistline.

Anyone seen wearing an Empress Josephine gown was assumed to be attending a costume ball.

Once they had eliminated the little white dress, Englishwomen went overboard. Fashions in the late 1820s became a kind of Regency Rococo: ornate, playful, sophisticated, lavish – a vibe not unlike the actual Rococo heyday of the mid 1700s. To emphasize nipped-in waists, corsets were longer and more tightly-laced, skirts were widened with gores in 1825-26, and when that didn’t create enough volume, from 1827 skirts were gathered.

To support all that fabric, undergarments (right) created the desired shape. In the late 1820s petticoats were corded with horsehair and sleeve “plumpers” were tied at the shoulders.

To avoid looking like pinheads, women balanced the scale with wildly over-sized that. By the end of the decade carriage doors had to be widened to accommodate the craze. In January, 1830 La Belle Assemblée chided those “…obliged to place her head sideways to ascend her carriage, her head-dress being wider than the panels of her coach door.”

But the undisputed star of the show was the sleeve, made huge to further emphasize tiny waists.

The Gigot Sleeve

The Marmaluke was a full length ‘puffy sleeve’ women wore well before the gigot made its first appearance in the blouses of Paris. Emerging around 1809, it was initially a soft, romantic look with partitioned puffs from shoulder to wrist, often sectioned by ribbon lengths. It became known as the Marie sleeve was overtaken in popularity by the gigot in the early 1820s.

In the years that followed, sleeves expanded to twice the width of the waist. Virtually every fashion columnist remarked on the silliness. Gigot, aka leg o’ mutton, sleeves were decried as unflattering and preposterous. To keep them looking puffy they needed support; some even had their own whalebone hoops. Despite their impracticality, women seemed to love them and huge sleeves would not start to shrink until Queen Victoria came to the throne.

La Belle Assemblée. Nov 1829. Recolored by Beatrice Knight

The most popular Regency variations were the ‘Donna Maria’ and ‘Imbecile’ illustrated (left) in La Belle Assemblée, Nov 1829. The caped “cherry color” carriage dress featured sleeves “…à la Donna Maria… finished at the wrists by pointed Spanish cuffs of velvet.” This sleeve was described as: “…though still very wide, and full at the top of the arm, [it] fits almost tight to the part from the wrist to the elbow, and proves that the possessor of a handsome and well-turned arm does not resort to those capacious sleeves to hide any repellent leanness or deformity.”

Next to it, the walking dress of violet gros de Naples boasted sleeves: “...à l’Imbécille, confined at the wrists by gold bracelets, dividing a double ruff of lace.”

Another popular sleeve shape was the demi-gigot, which flared from the shoulder to the elbow where it concluded in a tight, tubular forearm often encased in an ‘Amadis’ cuff, shaped like a gauntlet.

Lady’s Magazine. July 1830. Restored and recolored by Beatrice Knight

The Transformation is Complete

The Regency era drew to a close with the death of King George IV on 26 June, 1830. Over the next couple of months, fashion plates (right) illustrated the dramatic transformation of English women’s fashion during his reign: from Classical simplicity to Romantic/Gothic excess; from high Empire waistlines and lightweight stays to tight-lacing and exaggerated waists; from comfort to constraint.

The world had changed. English fashion creators would never again look solely toward Paris for inspiration. In fact, over the broader Regency epoch, it often seemed the French looked to London.

Sources

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. New York. Garland, 1989.

The Mirror of the Graces. Crosby & Co. London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London

The Modistes of Regency London

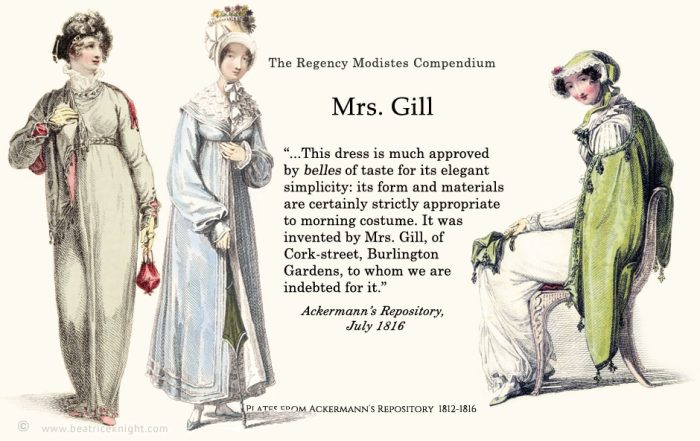

Mrs. Gill

Mrs. Gill was one of the leading modistes of the Regency, and pioneered the design of white wedding dresses at a time when few women of fashion wore them. She was also deeply involved [...]

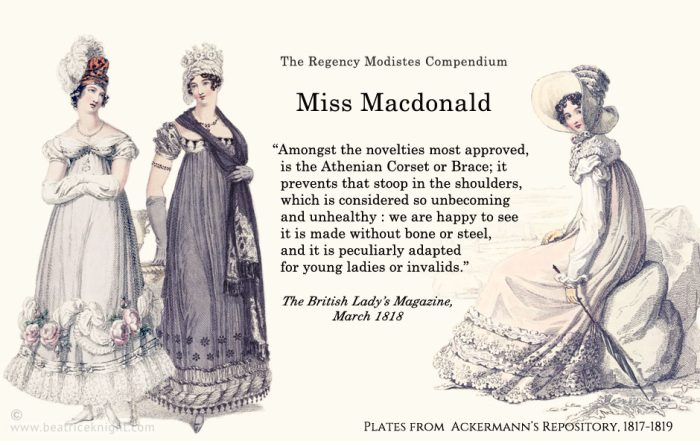

Miss Macdonald

Fashion has always been a copy-cat industry. One of the best known Regency modistes, Miss Macdonald (later Mrs. Smith) was ahead of the curve, creating designs and trim techniques that "inspired" many of her [...]

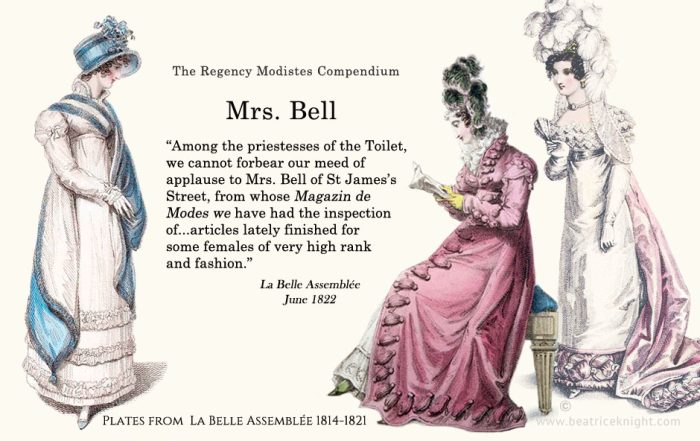

Mrs. Bell

Fond of declaring herself the inventress of this or that fashion, Mrs. Mary Ann Bell was not above purloining designs from other magazines and calling them her own. She was the great survivor of [...]

Miss Pierpoint

The self-declared "inventor of the Corset à la Greque," Miss Pierpoint was the busiest marketer of all the Regency modistes, with over 230 of her dresses appearing in fashion plates across multiple publications from [...]

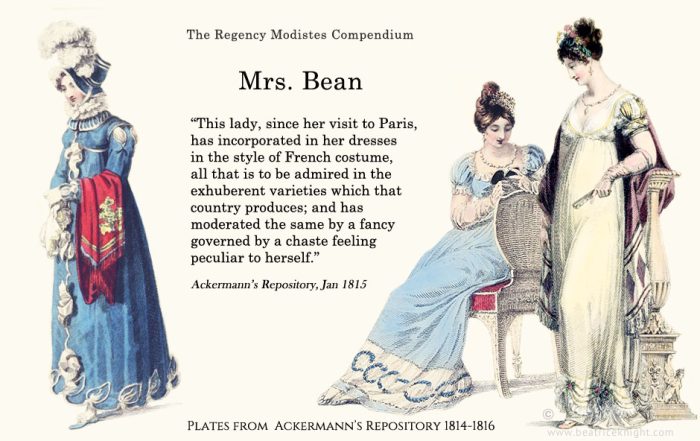

Mrs. Bean

A humble milliner in 1806, Mrs. Bean rose to giddy heights in just a decade, building a clientele of blue-bloods. In 1816, working with another leading modiste, Mrs. Triaud, she created twenty-six dresses and [...]

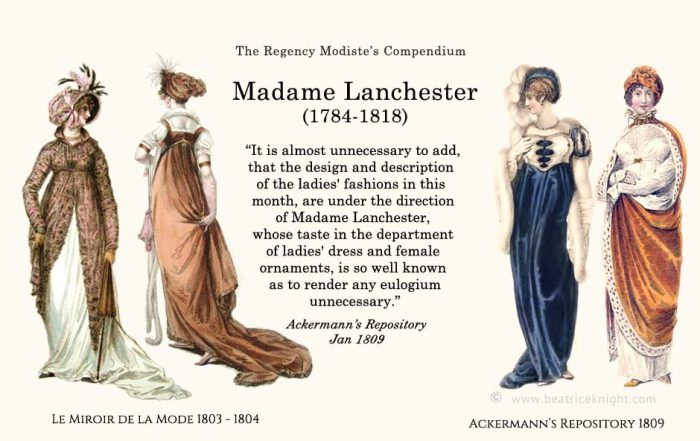

Madame Lanchester

By the time Regency modiste, Madame Lanchester was jailed for bankruptcy in Marshalsea Prison on February 8, 1812, she had spent more than a decade as one of London's best known milliner/dressmakers. Unfortunately, her [...]