When George became Prince Regent in 1811, Great Britain had been at war with Napoleon for seven years. Decoupled from Paris trends, English fashions had gone rogue.

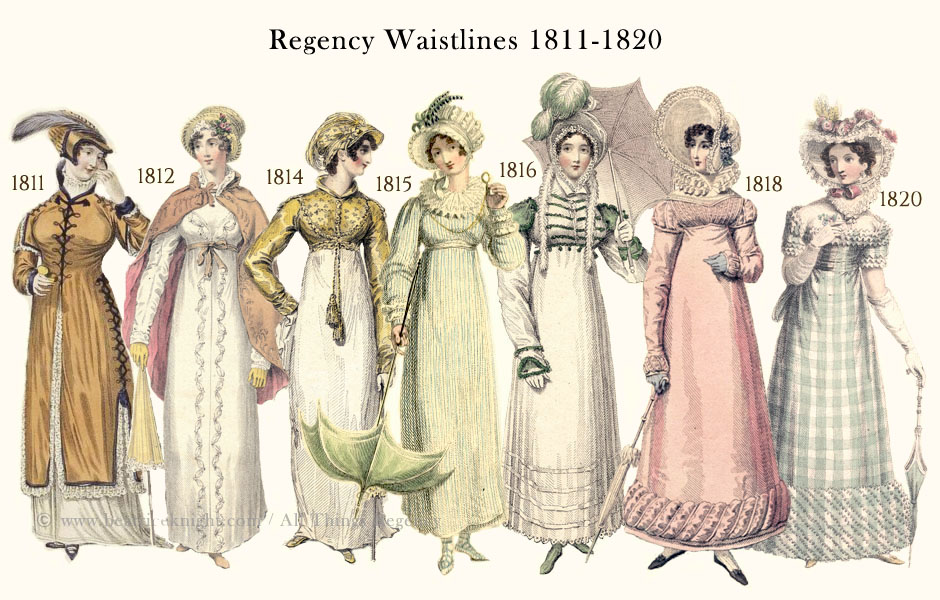

Regency Waistlines Part Two – 1811-1820

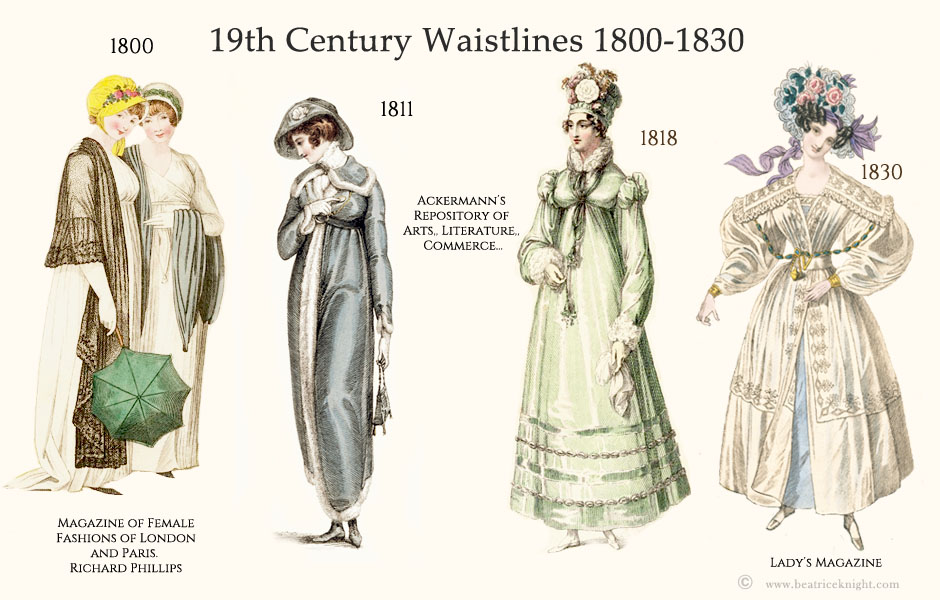

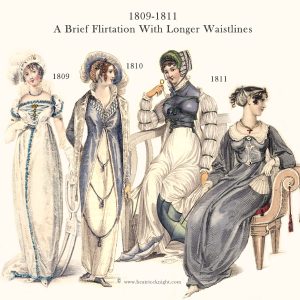

Having started the 19th century with Empire styles inspired by classical Greece and Rome, by 1811 English fashions were increasingly influenced by the Romantic movement and by public sentiment about the war with Napoleon. Waistlines had taken their first dive in the hot summer of 1808 and demi-trains had now vanished in streetwear.

Inch-by-inch, waistlines had lengthened since 1809 and bodices became more fitted to enhance the new silhouette. As the 1811 Season moved into full swing, waistlines were at their longest in 15 years. Official mourning for Princess Amelia had ended in February, and ladies of consequence set aside their black dresses and scarlet mantles in favor of respectful but pretty grays and lilacs. July 1811 brought La Belle Assemblée readers the “Kensington Garden Promenade Dress” (seated, second left ). This outfit exaggerated the feminine form with a corseted look using ribbons known as ‘Brandenburgs’ and went all-in on a puffy sleeve. 1811 foreshadowed an emphasis on the waist that would transform English fashion after 1820, but dresses were not yet at the natural waist. That was a bridge too far.

Inch-by-inch, waistlines had lengthened since 1809 and bodices became more fitted to enhance the new silhouette. As the 1811 Season moved into full swing, waistlines were at their longest in 15 years. Official mourning for Princess Amelia had ended in February, and ladies of consequence set aside their black dresses and scarlet mantles in favor of respectful but pretty grays and lilacs. July 1811 brought La Belle Assemblée readers the “Kensington Garden Promenade Dress” (seated, second left ). This outfit exaggerated the feminine form with a corseted look using ribbons known as ‘Brandenburgs’ and went all-in on a puffy sleeve. 1811 foreshadowed an emphasis on the waist that would transform English fashion after 1820, but dresses were not yet at the natural waist. That was a bridge too far.

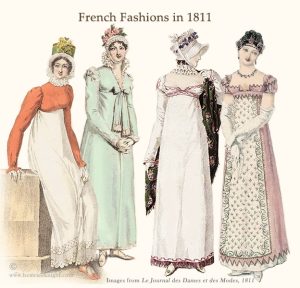

The Englishwoman of 1811 would have been startled by French fashions.

The Englishwoman of 1811 would have been startled by French fashions.

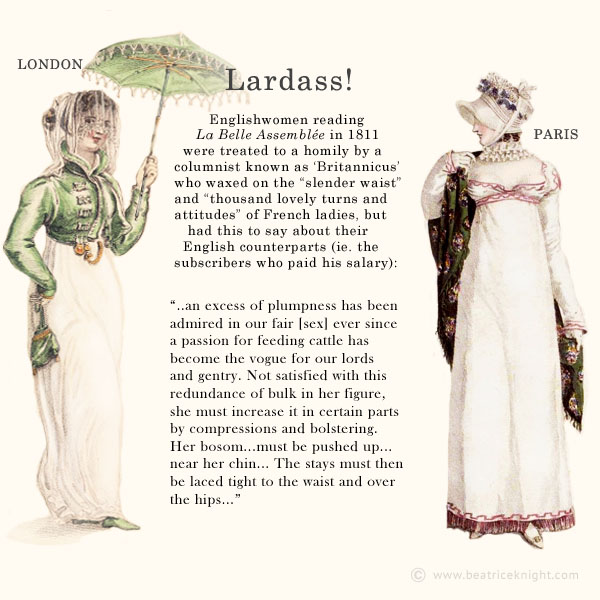

Largely ignoring the patriotic sentiments of middle class and working class people, English fashion magazines had spent the entire war fawning over French jauntée and tournure as if some gushy staffer was permanently stationed on the sidewalks of Paris. In reality, their columns on French fashions were ‘fake news.’ Any foreigners still in France had become detainees of Napoleon in 1803, and could not return home without a special dispensation. Suspected spies were harshly treated and letters were frequently censored or seized.

The fact was, after 8 years incommunicado, nobody on either side of the channel had the faintest idea what their counterparts were wearing. As 1811 rolled around, even La Belle Assemblée finally stopped pretending to have a finger on the pulse of French fashions. Their usual Paris column was initially replaced with a series of silly letters “from a Gentleman of rank and taste to a Lady of Quality,” waxing on about the history of fabrics and fashion.

Things went from bad to worse. In August, despite the news blackout on Paris fashions, subscribers to the costly magazine were lectured (below) about the charms of French fashionables by a gentleman calling himself Britannicus. By then, Englishwomen were adopting sterner corsetry for the sleeker bodices of the new silhouette, only to have their slimming stays decried by La Belle Assemblée as “impenetrable and hideous armor.”

La Belle Assemblée, 1811

If only they had known the awful truth. While English élégantes were experiencing rib-squeezing discomfort in 1811, just across the channel stays were flimsy, women were wearing their waists shorter than ever, décolletage was low, fabrics were crisp, and hemlines flitted dangerously near the ankle (see above). Ornamental detail was tasteful and beautifully sewn.

At no time in a hundred years had French and English fashions been so completely unaligned.

Waistlines Lurch Back Up: 1812-1814

Each year the beau monde began descending on London for the Season from February onward. Fashionable women would flock to their drapers and modistes to order the latest styles – which had been lurking ever nearer to the natural waist in 1811.

Imagine their heartburn when they wore their tight new stays and longer-waisted dresses to the Royal Academy Exhibition in May, only to see, as La Belle Assemblée gushed: “…a young lady of the most exalted rank” reveal the “exquisite contour of a fine Grecian form” in a neoclassical gown that harked back to the good old days of 1800.

Imagine their heartburn when they wore their tight new stays and longer-waisted dresses to the Royal Academy Exhibition in May, only to see, as La Belle Assemblée gushed: “…a young lady of the most exalted rank” reveal the “exquisite contour of a fine Grecian form” in a neoclassical gown that harked back to the good old days of 1800.

Well, that changed everything! The young woman, clearly a major influencer of her day, arrested the trend of the past year, and La Belle Assemblée’s July fashion spread gloated: “stays are now very much thrown aside” and “waists are considerably shorter than they were some months ago.” (meaning their previous issue). They duly featured the Classical-inspired evening dress (left) in their September issue, with a demi-short waist, as magazines had started describing it.

The rest of 1812 saw waistlines continue to shorten, and the trend continued for the next six years. Meanwhile Napoleon’s “empire” was swept away and so too was the white Empire look he had mandated. No one likes a loser.

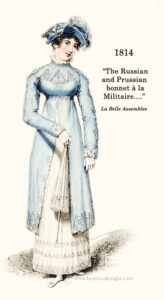

La Belle Assemblée, June 1814 fashions for July.

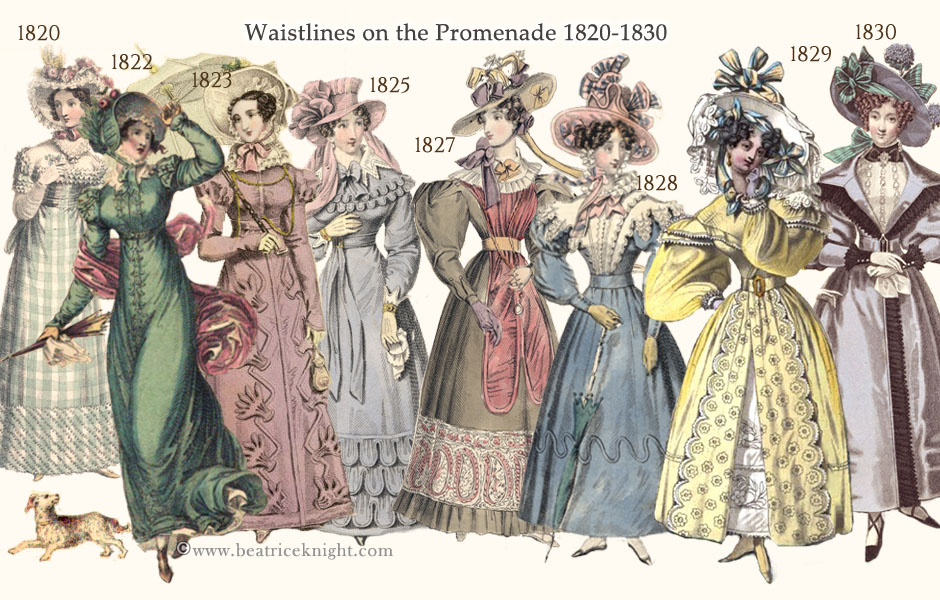

While the British were pummeling the French at Salamanca (1812) and Vitoria (1813), the Russians reminded the world why it’s a bad idea to invade their motherland, which Napoleon foolishly did. Big mistake. Huge. The tide of the war had turned and English fashion reflected the changing fortunes of the allied coalition. Women could not get enough of Russian wraps, Russian hats, Prussian hussar cloaks, and Circassian corsets. According to Ackermann’s, “…the Russian costume pervades every order of personal decoration… so much have the noble efforts and glorious achievements of the brave sons of the North possessed the minds of the applauding English that a la Russe is the general recommendary term for articles of comfort, decoration and utility.”

The walking ensemble (right) featured in La Belle Assemblée in June 1814 combines English heritage themes with a Russian & Prussian bonnet and pelisse.

Trying not to sound crestfallen that the French would not be ruling the world after all, La Belle Assemblée could not resist referencing “the jaunte air so peculiar to the French fashions…” but finally admitted: “…our fair countrywomen appear by no means inclined to encourage the introduction of Gallic fashions…” (Oct, 1814)

1814-1815: Napoleon is History

In the wake of the Battle of Nations at Leipzig in Octover 1813, Napoleon abdicated and was banished to Alba in April 1814. The countries duly exchanged prisoners and fashion mavens were gobsmacked to see the returning English hostages wearing the latest French fashions, and nothing was in step: hats, waistlines, trim, styling. Quelle horreur!

A year later, after briefly reclaiming power, Napoleon’s dreams of empire and immortality were crushed at Waterloo. At last élégantes could rush across the channel to see what their counterparts were wearing. While the English clutched their pearls over the very short waists and structured chic of French dresses, a few French naysayers thought English fashions dull and ugly (shocker!), but many were smitten with English romanticism, fabrics, trims, and charm.

Metaphors were inevitable, with some observing that French fashions had stagnated into parochial monotony, weirdly frozen in time, while English styles were confident, distinctive and vibrant. The winners get to write history. The world had changed. English fashion would never again revolve entirely around Paris. Indeed, as the third decade of the Regency epoch unfolded, it would seem to some that the French looked to London.

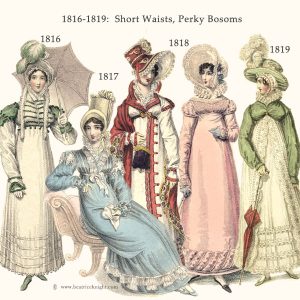

1816-1818: It’s All About the Bosom

In the initial rush to get back on the same page as Paris fashions, waistlines rocketed up after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The rounder, more natural look of the bosom that had prevailed a few years earlier would not do. Breasts had to appear uber-perky. To elevate them: the mysteriously described corset des Grâces, a short stay, basically served as the shelf bra of the late 1810s.

In the initial rush to get back on the same page as Paris fashions, waistlines rocketed up after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The rounder, more natural look of the bosom that had prevailed a few years earlier would not do. Breasts had to appear uber-perky. To elevate them: the mysteriously described corset des Grâces, a short stay, basically served as the shelf bra of the late 1810s.

With the abandonment of Neo-classical draping and rustic simplicity, fashions became fussier. After Napoleon was sent packing, trade could normalize and Englishwomen were no longer spending a small fortune to buy French trims smuggled through Gravelines. They were in hog heaven, embellishing every available inch of their ensembles with lace, braid, cording, frogging, fur, buttons, embroidery, tassels, bows, ribbon, ruffles, flounces. There was a lot to unpack.

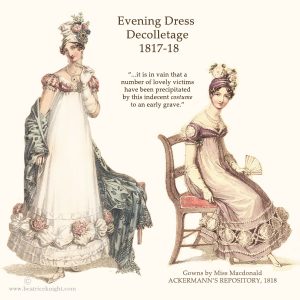

All the while, as gowns became ever more detailed and complex, waistlines climbed to new heights. In June, 1817, Ackermann’s Repository remarked: “…backs still continue very broad and waists are as short as ever…” Evening dresses were “…cut very low round the bust…”

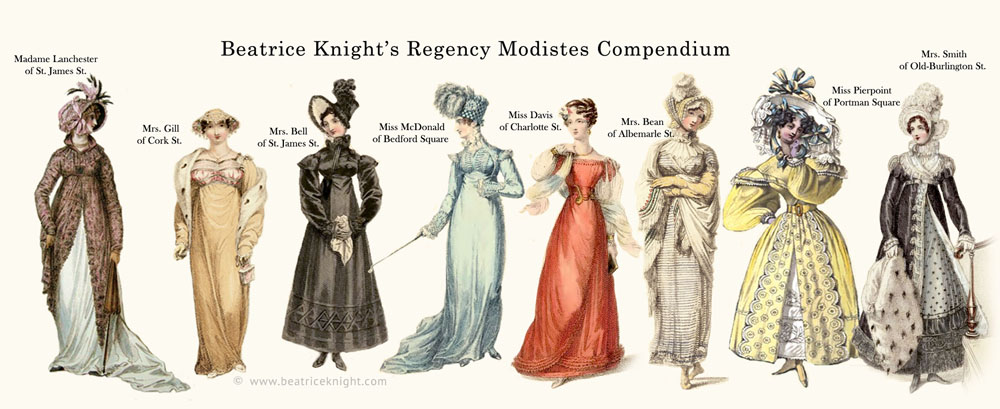

For the latest gowns with skimpy decolletage, the ‘fair votaries of fashion,’ as magazines were apt to describe wealthy women, looked to London’s most fashionable modistes. One-time darling of fashionables, Madame Lanchester, had gone bankrupt in 1810, leaving her shoes to be filled by her “pupil” Mrs. Osgood or a contemporary, Mrs. Gill of Cork St.

But no modiste better chaneled the vibe of the 1815-1819 years than Miss MacDonald of South Molton St. (see evening dresses below). Miss Pierpoint of Portman Square was a rising star at the time, who would come into her own in the 1820s. Soho modiste Mrs. Marchant was a go-to, and Mrs. Bean of Albemarle St. was known for her vibrant colors and luxury fabrics.

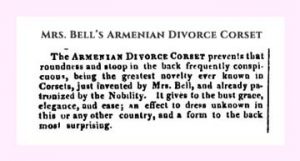

Another designer-dressmaker, Mrs. Bell, was eager to cater to the upscale clientele who read her father-in-law’s fashion magazine La Belle Assemblée. She penned the monthly fashion column that palpitated over her own designs and promoted her Magazin des Modes at 52 St James St. For more about these female entrepreneurs, check out the profiles of some leading modistes here.

To avoid wardrobe malfunctions in the wide, low necklines that dominated evening wear, some Regency women chose Mrs. Bell’s Armenian Divorce Corset (left), a design she hawked after returning from a buying trip to Paris in 1817.

There was also Mr. Marston’s “curious and splendid assemblage of patent stays” (sanctioned by the Royal family, no less). His shop at 24-25 Holywell St., Strand provided rooms “appropriated for the reception of the Nobility and Gentry, with respectable females to attend these…” (LBA, 1817).

The very low necklines came in for their share of condemnation, sometimes dressed up as concern for health (left). Since the style was worn by society’s leading ladies, most media was deferential, but Hannah More’s influence on English society increasingly obliged the upper classes to set an example for the ranks of the aspiring.

That fascinating topic is fodder for another post, but More’s impact on fashion was profound. She was the most widely read moralist of the Regency era, a celebrity among the country gentry and middle class. Reflecting her influence, dresses and corsetry became ever more restrictive as did women’s lives.

Queen Victoria, as a young married woman, was said to admire Hannah More above all other writers on women’s role. Arguably, without More, the Victorian era might have been very different.

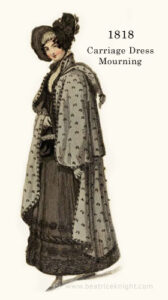

The Death of Princess Charlotte in 1817 put Mourning Fashions Front and Center

Ackermann’s Repository, 1818.

Nov. 6, 1817 plunged Great Britain into grief when Charlotte, the Princess of Wales, died in childbirth at only 21, delivering a stillborn son. The 50-hour labor and its tragic conclusion were so traumatic that the royal obstetrician, Sir Richard Croft, committed suicide a few months later. Prince Leopold, her husband, seems to have suffered some type of depression for the rest of his life; from all accounts they were passionately in love.

Among Britons, Princess Charlotte was as beloved as her father was detested. She would have been queen and her baby boy would have been king after her. The double loss sparked a tidal wave of heartbroken mourning unprecedented in Britain since the death of Lord Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805. Whig politician Henry Brougham wrote: “It really was as though every household throughout Great Britain had lost a favourite child.” Historians have compared the public outpouring with that for Princess Diana 180 years later.

Britain came to a complete, dazed halt. Even the poorest in the land scraped pennies for mourning clothes. Beggars made black armbands. Advertisements for black mantles, jet jewelry, black stockings and gloves filled the newspapers. Sales of colorful fabrics and trims collapsed; desperate manufacturers petitioned the government to end the mourning period lest they went bankrupt.

Despite deep mourning, evening dresses still flaunted expanses of naked flesh. Two months into the mourning period, Ackermann’s featured the fashion plate (aove, left), a design by Miss McDonald of Wells St.

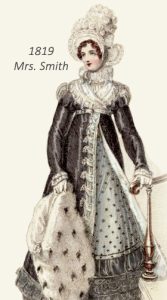

Mourning and half-mourning became a theme of 1817 to 1820, with the deaths of Queen Charlotte (Nov. 1818) and King George III (Jan. 1820). Throughout the period, waistlines remained very short, but once your breasts are jammed up toward your chin, there is nowhere else to go. The trend hit its giddy height late in 1818, and as 1819 progressed, waistlines began to drop a little.

As the calendars flipped to 1820, it was soon clear that a transition was underway. The Prince Regent became king in January 1820, and the next decade, during his reign as King George IV, would see dramatic change in English fashion.

Discover the Modistes of Regency London

Sources

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. New York. Garland, 1989.

The Mirror of the Graces. Crosby & Co. London

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London

Sitwell, Sacheverell and Moore, Doris Langley. Gallery of Fashion 1790-1822. Batsford, 1949.