The white wedding dress is often dated back to Queen Victoria, who made it must-have bridal attire. But by the time she went up the aisle, Regency brides had been rocking white for twenty years.

Regency Brides

Imagine you are a young Regency woman, living the dream–the Honorable Miss Somebody from country gentry and you’ve just gotten engaged to an eldest son of rank. Once you are married, you’ll make your curtsey to the Queen at one of her ‘Drawing Rooms,’ and you and your dashing new husband will be invited to the most glittering events of the London Season.

Unless your family is swimming in cash, it’s going to be tough to cover the cost of both a wedding dress and a court dress, along with your trousseau and the marriage portion. To stretch the budget, your wedding dress will have to do double duty as a ball and opera gown. Perhaps a good modiste will be able to make it over as a fancy hooped court dress. It would help if the dress was white, of course, since that’s the color unmarried and newly married women are expected to wear to court.

Perhaps this is what convinced a young beau monde fashion influencer to choose a white wedding dress in 1810, which she then wore to multiple events. La Belle Assemblée (April) referenced the gown as “lately the dress of a bride” in a matter-of-fact manner that suggests there was nothing new or outlandish about the idea of a white wedding dress. Evidently, the trend not only existed; it had reached normalcy status in print media. The “little white dress” – that Regency cliché – was about to get the biggest boost in its history: as bridal wear.

What Regency Brides Usually Wore

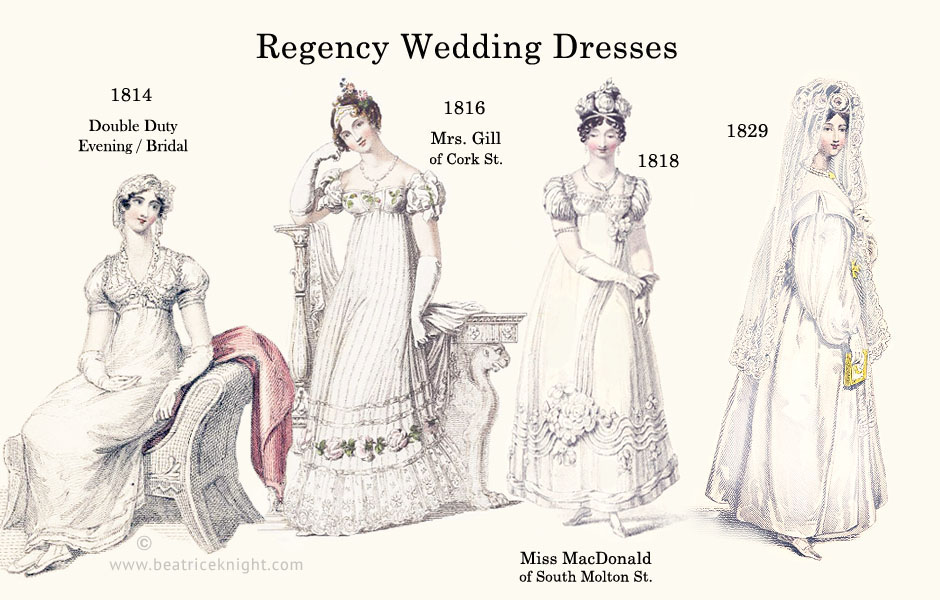

At the start of the 1800s very few women wore white wedding dresses, and even fewer had a dress made specially for their wedding day. Working class brides usually wore their Sunday best. Those who had saved for a new gown, chose something practical they could wear for special occasions until it would not longer fit. Women of greater means would have a fine evening or dinner dress made over as a wedding gown, and then continue to wear it for years after. Even wealthy women expected their wedding gowns to do double duty, and since they attended upscale social events, their wedding dresses had to look like evening wear – silver was especially popular.

English fashion magazines featured plates of ‘full dress’ and ball dresses that could easily be worn by a bride, but until 1816, none of these was promoted as a wedding dress, per se. However, a series of factors converged.

- Napoleon Bonaparte had been kicked to the kerb and everyone felt like partying

- British fashion had gone rogue during the war and forged its own identity – heavily influenced by Romantic era sensibilities

- when the war ended in 1814-15, so did the embargo on French lace and fabrics

- the new generation of young women wanted to do something different from their mothers

- the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution placed machine-made lace within the reach of working people

- peace brought prosperity to a rising middle class seeking to create memories and traditions their parents could not have aspired to

When Napoleon was finally sent to exile on St. Helena, a sense of optimism swept England. Men returned home. Young women, having their first Season free of the war, were ready to embrace something new and fresh. They suddenly had suitors and would soon marry and take their place in society. London’s upscale modistes saw a business opportunity and responded.

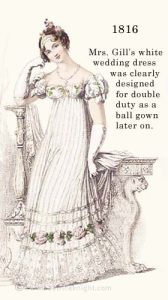

The first to make a name for herself in wedding dress design for the beau monde was Mrs. Gill of Cork Street, sometimes credited as the “inventor” of the white wedding dress. In 1816, her design (left) was the first to be promoted expressly as a white wedding dress in a fashion publication. Ackermann’s Repository described it as: “a wedding-dress which she has recently finished for a young lady of high distinction…” made of “…striped French gauze over white satin…with a deep flounce of Brussels lace…” The gown was clearly designed for double duty as evening wear; it’s virtually indistinguishable from the ball gowns seen that year.

The first to make a name for herself in wedding dress design for the beau monde was Mrs. Gill of Cork Street, sometimes credited as the “inventor” of the white wedding dress. In 1816, her design (left) was the first to be promoted expressly as a white wedding dress in a fashion publication. Ackermann’s Repository described it as: “a wedding-dress which she has recently finished for a young lady of high distinction…” made of “…striped French gauze over white satin…with a deep flounce of Brussels lace…” The gown was clearly designed for double duty as evening wear; it’s virtually indistinguishable from the ball gowns seen that year.

The first expressly bridal Regency wedding dress – just my opinion – was created by influential London modiste, Miss Macdonald. whom I researched in detail for my modistes’ compendium. Her 1818 design characterized the “big day” dress with unique trim and head-wear unlike anything typically seen in a ballroom. It placed bridal fashion in a lane of its own, where it has remained ever since.

The first expressly bridal Regency wedding dress – just my opinion – was created by influential London modiste, Miss Macdonald. whom I researched in detail for my modistes’ compendium. Her 1818 design characterized the “big day” dress with unique trim and head-wear unlike anything typically seen in a ballroom. It placed bridal fashion in a lane of its own, where it has remained ever since.

By the early 1820s London’s leading modistes and even some warehouses were promoting white wedding dresses. There was no looking back. By the time Queen Victoria jumped on the bandwagon, fashionable women had been wearing white wedding gowns for over twenty years.

How Royal Influence Propelled the White Wedding Dress

Although Queen Victoria elevated the white wedding dress to cultural icon status, she was not the first British queen to rock the look. Philippa of England wore a white silk tunic and train, trimmed with ermine and grey squirrel, when she married Scandinavian prince, Eric of Pomerania at Lund Cathedral in 1409. Her wedding was well documented, including a description of her gown. Mary Queen of Scots wore white when she married the Dauphin of France in 1558, and although some aristocrats followed the royal example through the years, it was Queen Victoria whose dress inspired women of all ranks to follow suit. Not only was the young queen an “influencer,” her timing was impeccable. Sentimentality and romance were touchstones of the Victorian era, and white lace and silks had never been more affordable, thanks to the Industrial Revolution. For the first time in history, a beautiful white wedding dress was within the reach of an average working family. They went all in, and the bridal industry as we know it, was born.

What About the French?

Some researchers credit the French with originating the Regency white wedding gown. It’s certainly true that French publications featured white wedding gowns well before their English counterparts, but they were hardly breaking new ground. Traditionally white was a mourning color in France, however it came to symbolize joy as time went by, and Emperor Napoleon loved the classical symbolism associated with white gowns. His fashion edicts mandated white Empire styles for upper class women, and as the 1800s unfolded, French women virtually lived in white percale for morning and walking wear, then switched to white silk and crepe for evening. It would have raised eyebrows if a fashionable young Parisian bride wore anything but white, although the 1813 gown (left) features a light green false hem beneath the white lace skirt.

Some researchers credit the French with originating the Regency white wedding gown. It’s certainly true that French publications featured white wedding gowns well before their English counterparts, but they were hardly breaking new ground. Traditionally white was a mourning color in France, however it came to symbolize joy as time went by, and Emperor Napoleon loved the classical symbolism associated with white gowns. His fashion edicts mandated white Empire styles for upper class women, and as the 1800s unfolded, French women virtually lived in white percale for morning and walking wear, then switched to white silk and crepe for evening. It would have raised eyebrows if a fashionable young Parisian bride wore anything but white, although the 1813 gown (left) features a light green false hem beneath the white lace skirt.

As the Napoleonic war dragged on, war embargoes and travel restrictions prevented English women from following French fashions. When peace finally broke out in 1814-15, both sides were stunned when they crossed the channel. The English thought the French seemed stranded in time, clinging to Empire despite their ignoble defeat. The French deemed English fashions frumpish and fussy.

By then, London was a fashion capital, and English manufacturers had stepped into the breach left empty by French blockades. Anglomania would sweep French fashion in the 1820s. Brides on both sides of the channel kept wearing white.

Learn More About Regency Courtship and Marriage

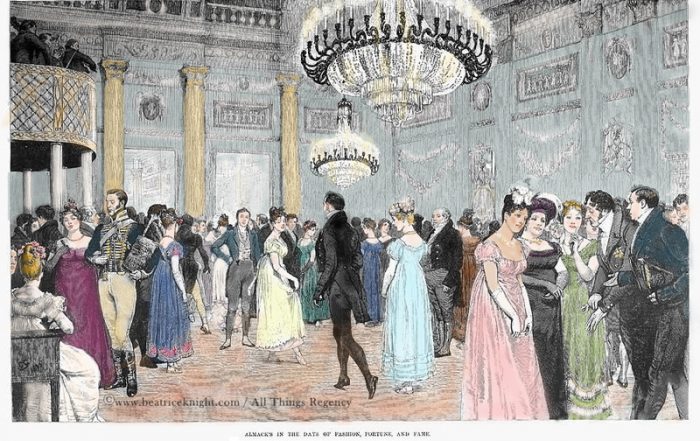

Almack’s History

As Ton Central for Regency high society, Almack's was all about exclusivity. That meant keeping out “mushrooms” (rich social climbers) and other undesirables. Almack's - a History To keep things classy, [...]

Regency Matchmakers

Regency Matchmakers: In 1810 at the Court of Chancery a marriage broker took legal action to recover fees from a client who refused to pay when he failed to snare [...]

Sources

La Belle Assemblée. J. Bell. London

The Lady’s Magazine. G. Robinson. London

The Lady’s Monthly Museum. Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. London

Laudermilk, Sharon and Hamlin, Teresa L.. The Regency Companion. New York. Garland, 1989.

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. R. Ackermann. London

Philippa of England at Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon