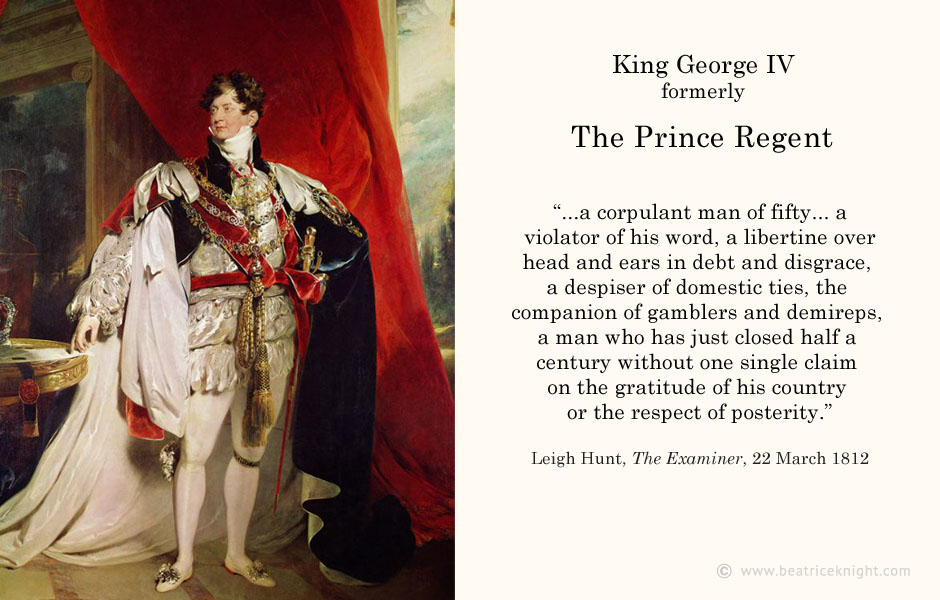

Marriages between the upper echelon families of England were transacted much as mergers and acquisitions are in today’s business environment. Each Season, the latest crop of prospects were introduced to the marriage market, with their respective inducements, and the negotiations began.

Presentation at Court

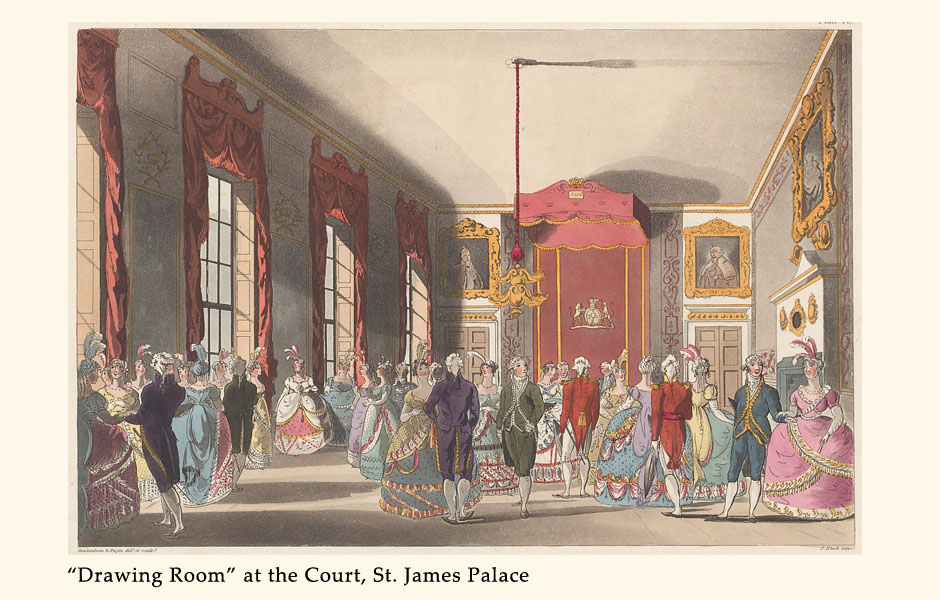

Young Regency women entering society were not presented at court en masse, as seen in the highly-organized débutante rituals of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. When the 1800s began, it was customary for girls had their ‘come-out’ when their mothers decided they were of marriageable age, usually at 17-18 years. Families of the first stare aimed to present their marriageable daughters at court, but opportunities to do so were haphazard. Girls had to wait for one the Queen’s so-called “Drawing Room” courts held at St. James Palace.

It would have been convenient for 21st century Regency novel writers if these events were held according to a predictable schedule. However, the only Court date firmly fixed on the Regency calendar was Queen’s Birthday on January 18th, and débutantes were not presented there, unless by personal invitation – for example, Lady Nelson was permitted to present her daughter to the queen at her birthday Drawing Room in 1807. Most hopefuls had to wait for an afternoon Drawing Room, usually held in March or April, expressly to enable newcomer presentations (they were not known as ‘debutantes’ until the 1830s). When a Drawing Room date was settled, the Lord Chamberlain would contact those wait-listed for the occasion.

Planning a young woman’s first London Season began long before she arrived in town. To obtain a court presentation, her mother, or the female relative had to file a request with the Earl of Morton, Queen Charlotte’s Lord Chamberlain. It would read something like this: “Lady Whomever desires the Their Majesties’ gracious permission to attend one of the Courts and present her daughter.” The cut-off date for this formal request was January 1st, and not just anyone could apply. To keep out nouveau riche pretenders, requests were accepted only from matrons who had been presented at Court.

A few weeks before the designated Court, a Summons card would arrive stating that the Lord Chamberlain “…has been commanded by Their Majesties to summon the Countess of Yaddyadda to the Court on whatever-date.” This was an order, not a discussion. The Court proceeded even during times of full mourning.

La Belle Assemblée, July 1, 1807. Re-tinted by Beatrice Knight.

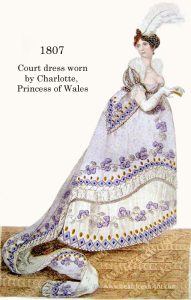

The Big Dress

While the royal princesses were seen at court in lavish gowns such as the one (left) worn by Princess Charlotte to the Queen’s Birthday in January, 1807, unmarried and newly married young women wore white gowns and simple jewelry (usually pearls and diamonds) for their first court date. By the time the coveted summons arrived, the presentee and her sponsor would be having the final adjustments made to their pricey, elaborate court dresses.

Some Georgian customs were updated during the Regency; the infamous hopped court dress was not among them. Not a woman at the cutting edge of new trends, Queen Charlotte followed the traditions long-established before her husband was crowned. These dictated skirts with hoops and trains, plume head-wear, lappets, gloves, and fans. Plumes featured ostrich feathers (always white for débutantes ), usually secured by a diamond bandeau and attached to the mandatory lace lappets which fell past the shoulders.

Regency women “modernized” the look of court dresses by shortening the waist in a nod to the Empire silhouette. The result was a hooped monstrosity that made the wearer look rather like a small lid perched atop a large teapot. Court dresses did not come cheaply and could not easily be adapted for any other purpose – they were far too unfashionable to be worn to the opera or a ball. But perhaps they were not without their advantages. Some have joked that with so much standing about in the Court and a dearth of retiring rooms, a woman could find a dim corner and slip a bourdaloue under her massive skirt, if nature called. Others jested that a lover could be smuggled into Court beneath the skirt and help his lady pass the time more pleasantly.

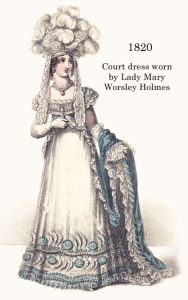

La Belle Assemblee. August, 1820. Recolored by Beatrice Knight

When the Prince Regent became King George IV, court fashions finally left the 18th century behind. “By order of the King,” big hoops became passé overnight. Lady Worsley Holmes wore the gown (right) to the new king’s first Drawing Room, and the silhouette of the day found reflection in court dresses, moving forward.

The Big Day 1800-1813

Decked out in their finery, newbies would arrive for the queen’s Drawing Room at the “old palace” of St. James by about 11.00am and spend the next few hours in ante-rooms milling about while they awaited the queen. In the meantime, Her Majesty and whichever of the princesses would attend the court that day, would head from the Queen’s Palace to the Duke of Cumberland’s apartments at St. James Palace a little after 12.30 pm. After eating a luncheon of cold collations, they would don their court dresses and embark on a stately progress through the gallery, ballroom, and state-rooms to the Council Chamber, escorted by the Duke of Kent or another male relative, along with the Lord Chamberlain and the usual suspects.

At 2pm, the queen and the princesses would take their places in the Drawing Room. King George III and his entourage also attended the queen’s Drawing Room in the earliest years of the 1800s, but as his illness advanced, the king was rarely seen at court. During his reign, a newbie, so long as she was originally invited to court under the sponsorship of an approved lady, could make her curtsey alone, introduced by the Lord-in-Waiting. Most, however, attended with their sponsor, and on hearing their names announced, Lady Whomever and the young lady would approach the ‘Royal Presence.” The young lady would step forward, make a deep curtsey, and answer if spoken to. Then, walking backwards, she and Lady Whomever would make their exit, having received the requisite stamp of approval.

Girls of the very highest rank were sometimes given a kiss or handshake by the queen

The next few months would be a giddy whirl of balls, parties, hopefully culminating in at least one serious suitor made of the ‘right stuff.’

A new debutante presentation format emerges in the 1820s

In the later years of King George III’s reign, illness put a damper on his court appearances. In those days, most young women entered society without making a curtsey at one of the queen’s Drawing Rooms, anyway, but being presented to royalty still conferred a coveted social cachet.

When Prince George became Regency, he was estranged from his wife, so drawing rooms were held by his mother, Queen Charlotte. The most notable of these was held in 1816 to receive congratulations on the marriage of young Princess Charlotte (the Prince Regent’s only daughter and heir to the throne) to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Cobourg. There was such a huge throng, only a select few young ladies were presented, all of them in white gowns. Queen Charlotte held drawing rooms through the Regency and continued to do so until her health failed in 1818.

When the Prince Regent came to the throne in 1820, change swept through the court. Hoops were swept into the dustbin of history, although the customary trains, ostrich feathers, and lace lappets would remain a fixture: in fact, the new king liked ostrich feathers so much, instructions handed down ahead of each Drawing Room mandated more of them for plumes. The new king promised Drawing Rooms would become a regular event, and in a major break from tradition gazetted in May 1821, ‘by Order of the King,’ debutantes would be presented henceforth at King’s Birthday courts. The king subsequently designated 23 April (St George’s Day) as his official birthday.

In practice, this marked the the beginning of mass presentation of debutantes at the British court. In 1822, the King’s Birthday court reflected the changes in a massive, glittering affair that included, in addition to the customary presentations of newly married society women, notables returned from abroad, and military men receiving recognition, well over 100 debutantes. Despite the king’s intention to make these presentations an annual milestone, illness saw courts postponed on multiple occasions in the years that followed. In 1823, the disappointment of junior branches of the nobility was reported (British Press, 24 April) as “extreme” among those “who were to have been presented to His Majesty preparatory to their appearing in public parties.”

The 1824 Drawing Room finally took place on 20 May, after postponements for weather and illness. With it came another significant change of rules. The Lord Chamberlain gave notice, a few days ahead, that presentations would no longer be made by the Lord-in-Waiting (the stand-in if a young lady came to court by invitation, but without her sponsor). The new ruling formalized the process for presenting a debutante – from 1824 onward, she must be presented by her sponsor or another woman who, herself, had been presented previously. This format would remain until

Drawing Room courts return to St. James Palace

After several postponements, the Drawing Room was finally held on 20 May, 1824 at St. James Palace, marking the first time in a decade that a court was held there, the former king and queen having long ago discontinued their regular king and queen’s birthday courts at the “old palace.” King George IV had since overseen extensive improvements. Instead of getting out of their carriages in the rain and damaging court dresses, waiting outdoors, there were now covered colonnades. The indoor rooms were almost unrecognizable, with walls removed, beautiful new lighting and décor, and paintings no one had seen before on all the walls.

Excited to see the renovations, the fashionable world turned out in huge numbers, waiting in a procession of carriages for hours before reaching the palace. Newspapers reported one of the largest throngs ever to cram the court. Two years had passed since the last presentation and pent-up demand saw over 220 young women make their first curtsey.

Sporadic Drawing Rooms

1825 was marked by postponements of the King’s Birthday court yet again. He held a levee at Carlton House for his birthday in April and postponed the Drawing Room a couple of times before eventually cancelling it. 1826 was another disappointment, with the king holding his only levee for the year on November 27, and in the custom for levees, the only presentees were gentlemen. In 1827, the election of a new prime minister (Mr. Canning) and parliamentary shuffle accompanying the change of government seemed to pre-occupy the court. Deprived of the anticipated Drawing Room courts, young women could at least use the fashionable court dresses for balls .

Finally in 1828, on 23 April, the king held a Drawing Room. Because such a long time had elapsed since the last one, it was heavily attended, with hundreds of young women finally getting their long awaited presentation. On 30 April, 1829 the king held one of the most attended Drawing Rooms ever, with over 1000 women attending, of whom at least 300 were new to the court. It would be his last. A year later, the court planned for 23 April, 1830 was postponed to 7 May, then cancelled because of the kings illness. He died soon after, on 26 June, 1830.

There would not be another Drawing Room until King William IV came to the throne. Happily married rather late in life to Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen he and the queen held a Drawing Room in February 1831 to celebrate Queen’s Birthday, which also marked the first public appearance of Princess Victoria, then just 11 years old. Fashion magazines were packed with court dresses in 1831, which is not surprising for Queen Adelaide had already held her sixth Drawing Room in May. She continued to be diligent in holding courts, and established for young women the regular presentation system Queen Victoria would formalize on a larger scale when she came to the throne in 1837.

In Victoria’s reign, Drawing Rooms featuring mass presentation of debutantes were held four times yearly, twice before Easter and twice after, at Buckingham Palace. The traditions she maintained remained almost unchanged until the 20th Century. The last time traditional ladies court dress, with plume and lappets, was worn was in 1939, on the eve of World War II.

Having been postponed during the war, so called “presentation parties” resumed at Buckingham Palace in 1947, however with most of the population living on rations and trying to rebuild in the post-war era, the idea of a small elite holding fancy balls and spending fortunes on big dresses was tone-deaf at best. The Buckingham Palace events had also become broader in scope, making vetting a more time-consuming process and the debutantes “less select” than in the past. Finally the court announced that presentation parties would end in 1958. Princess Margaret later remarked: “We had to put a stop to it. Every tart in London was getting in.”