The Prince Regent

“Like most of society, Aunt Stirling had a better opinion of night soil than of the Prince Regent.” Alverstone by Beatrice Knight

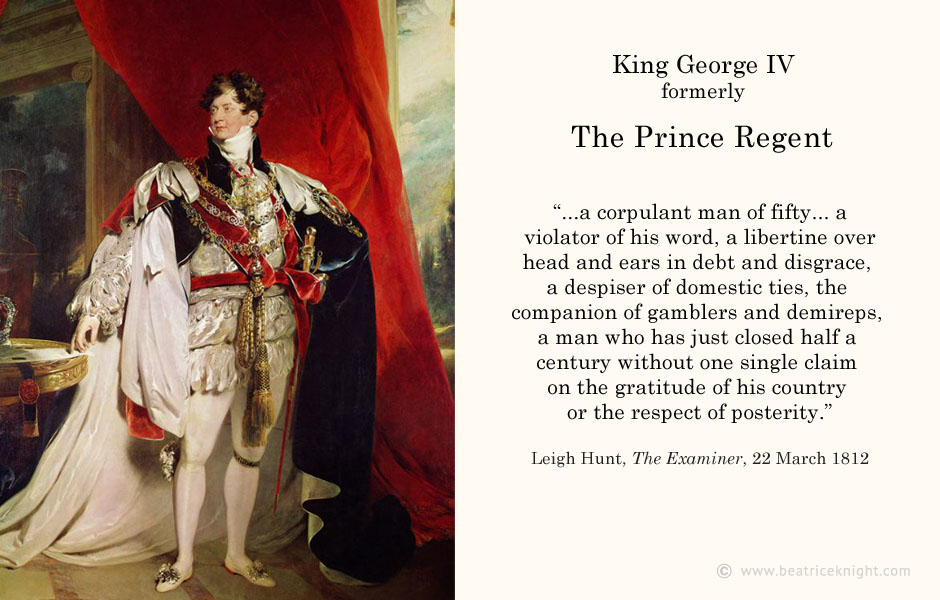

The Prince Regent was viewed with nearly unanimous contempt by his contemporaries, and much like today’s entitled ruling elite, he was self-obsessed, thin-skinned, tone-deaf, and claimed victimhood if anyone had the nerve to criticize his conduct. Admittedly, he was a royal 260 years ago, when self-scrutiny was not a thing. It probably didn’t help that he spent his entire life surrounded by fawning courtiers who agreed with everything he said.

Born George, Prince of Wales in 1762, and nicknamed Prinny, he was the eldest son of King George III and heir to the British throne. His father struggled with mental illness and the prince hovered in the wings lobbying to be declared Prince Regent once the king proved unfit to rule. The movie, The Madness of King George, chronicles this personal power struggle and the politically charged atmosphere in which it took place.

The prince would finally have his moment when the king’s youngest daughter and favorite, Princess Amelia, died in November 1810. Crushed by grief, the king sank rapidly into a mental decline from which he would never recover. As soon as the official court mourning period ended, parliament passed an act declaring George Prince Regent, to rule in his father’s stead.

His regency continued until his father died in 1820. He was then crowned King George IV and reigned for the next decade. Literally speaking, the Regency era spanned the nine years from 1811-1820, when he was Prince Regent. However, historians generally the entire late Georgian period from 1795 until Queen Victoria took the throne in 1837. This broader timespan recognizes the unique cultural and social characteristics synonymous with Regency politics, fashion, architecture, and the arts.

Opposing Tides

At a time when the greatest aristocrats and leaders were shaped by a sense of noblesse oblige largely absent among the 21st century elite, the foppish Prince Regent did little to earn the respect of his subjects. He was extravagant, indolent, vain, and could be callous, mean-spirited and petty. Yet he was also gifted and highly educated, witty, generous to those in his charmed circle, and a serious patron of the arts and sciences. The era itself embodied opposing tides, charged by the broader Romantic movement; influenced by the ideals and impacts of the French Revolution; and overshadowed by the long, costly war with Napoleon.

George Cruikshank, 1816.

The public might almost have overlooked the Prince Regent’s wastrel habits, but his neglect of his only daughter, Princess Charlotte of Wales, provoked intense condemnation. The young princess was a blank canvas on which could be written the hopes of a nation disillusioned by her father. She symbolized the future. The Prince Regent, by contrast, was a boil festering with poison from the past.

The princess spent her childhood caught in the crossfire between parents who loathed each other. Each of them used her as a pawn. The prince imposed complete seclusion on her, a life of nursery routines that took no account of her age, interests, and stature as the expected future queen. In response to a please from the princess’s lady companion Cornelia Knight, the Prince Regent said: “Charlotte must lay aside the nonsense of thinking that she has a will of her own…she must be subject to me as she is at present, if she were thirty, or forty, or five-and-forty…”

His callousness and hurtful snubs did not go unnoticed in the public sphere. No royal has ever been lampooned with such relish. James Gillray and Thomas Rowland caricatured the prince over everything from his many mistresses to his debts. The cartoonist George Cruikshank defined the prince in 1814 as “The Grand Entertainment” and skewered him in depictions that mirrored public opinion. Everyone had something to say about his marriage and unhappy daughter.

His own family viewed him as an embarrassing sideshow and lost no time, after his death, in erasing the evidence of his senseless extravagance. His brother, who succeeded him as King William IV demolished most of the Royal Lodge at Windsor, tore out the newly installed gas-lights in the castle and halted its lavish redecoration. A trove of furniture was sent to the auction block along with Prinny’s wardrobe of costly clothing. Queen Victoria finished the task decades later by demolishing the Chinese Fishing Temple he had built in his retreat at Windsor.

As for his subjects, never had a monarch’s death been mourned less. From all accounts his funeral was poorly attended and the public spent the day enjoying themselves in alehouses. The Times had these consoling words to offer: “Nothing remains to be said about George IV but to pay, as pay we must, for his profusion.”

Read More

Ashton, John. Social England Under the Regency, Vol.II. London. Ward and Downey, 1890

Gronow, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow

Parissien, Steven. George IV: the Grand Entertainment. London. John Murray, 2001

Stott, Anne. The Lost Queen. Pen & Sword History, 2020

Kaye, J.W. Autobiography of Miss Cornelia Knight, lady companion to the Princess Charlotte of Wales. London. W.H. Allen