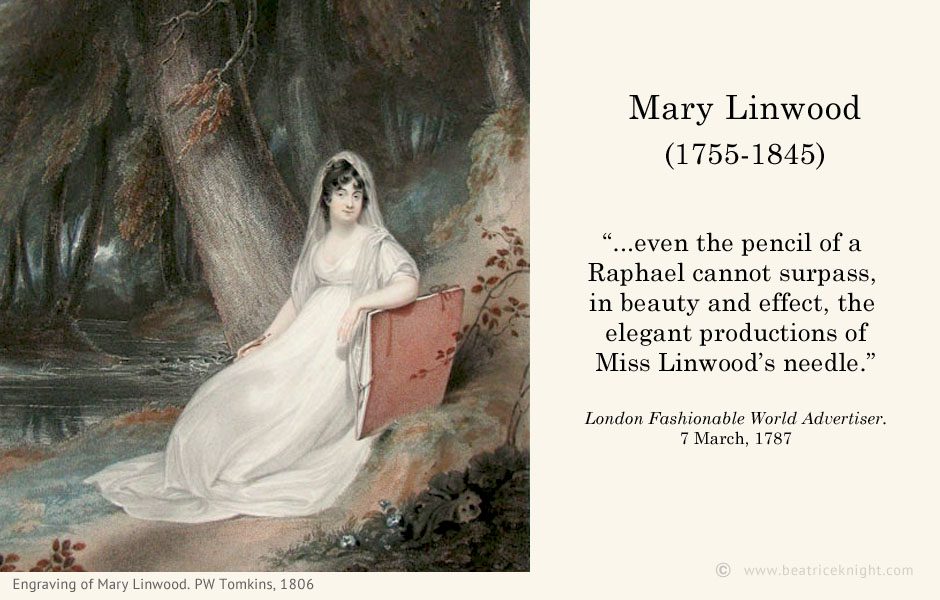

There were few “respectable” self-made women in the Regency era. Mary Linwood made her fortune in needlework. At the height of her fame, Russian Empress Catherine the Great offered to buy all her “stitchery paintings” for £40,000. That’s about US$3,000,000 in today’s money.

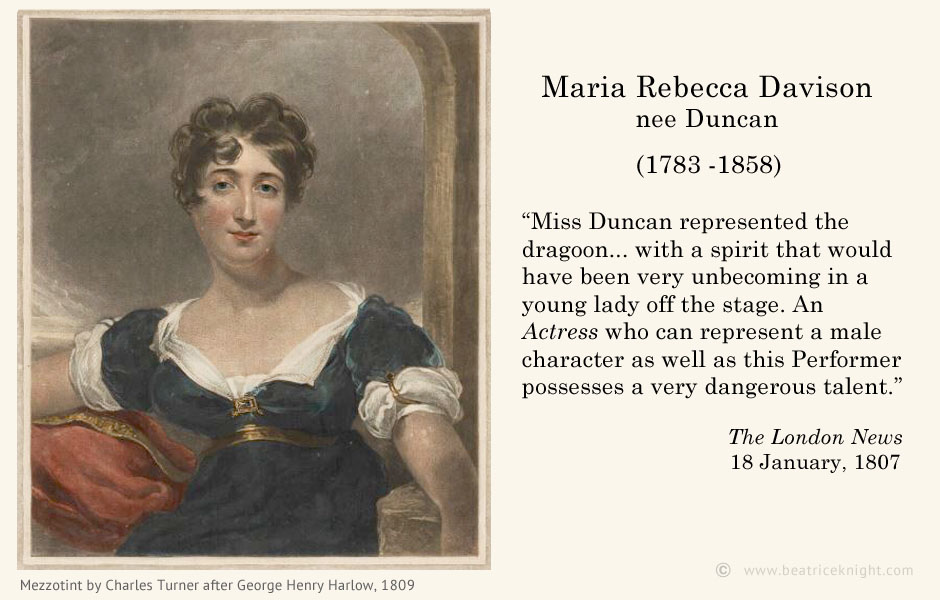

Mary Linwood – Stitchery Tycoon

Mary Linwood, embroidery ca. 1798. Salvator Mundi, after Carlo Dulci

When Mary died of flu at almost 90 years old, her entire collection fetched a mere £300 at auction. The “needlepainting” phenomenon had done its dash and no one seemed sure what the fuss was all about.

Miss Linwood had a good run. Her career lasted 50 years, during which she turned a feminine accomplishment into international celebrity. Long before the age of social media, she was a clever self-promoter and publicist. Her fandom included the great and powerful of the day—Queen Charlotte, Queen Victoria, Napoleon Bonaparte, Talleyrand, Empress Catherine of Russia, and the King of Poland, among others. She declined an offer from the Marquis of Exeter of £3,000 for Salvator Mundi, after Carlo Dolci (right).

While most genteel girls born in the Georgian era treated needlework as a pastime, Mary seemed focused on making lemons into lemonade from her early teens, creating her first “painting” at only 13 and finishing four by 20. Her father had gone bankrupt when she was very young and her enterprising mother Hannah Linwood Turner kept the family afloat by establishing a successful private boarding school for young ladies in the Priory, Belgrave Gate. After her mother’s death, Mary continued as its owner and headmistress for 50 years.

Born in 1755, Mary was only thirty-one when she successfully exhibited at The Panthenon, Oxford Street in 1787 and then in the Hanover Square Rooms in 1798 and then built her “brand” by exhibiting in Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast, and Dublin, and around Europe and Russia, rubbing elbows with crowned heads and leading “influencers” of her generation. Her success was such that she could commission the famed John Hoppner to paint her portrait.

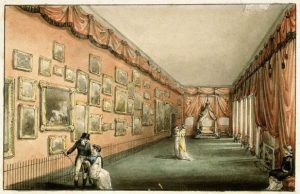

Mary Linwood Gallery @ Victoria & Albert Museum

In 1809 she established a permanent gallery at Savile House, Leicester Square, in what was once Sir Joshua Reynolds’ studio. Her exhibition was the first to use gas lighting, extending opening hours until late each afternoon. Charging a shilling a head, she hauled in some 40,000 patrons a year. Perhaps she was wise not to sell her collection to the Russian empress, after all. Over her life, until the exhibition finally closed in 1845, it earned the equivalent of around US$7.5 million.

Her Savile House gallery was a tourist attraction lauded in Curiosities of London and Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitors’ Guide to its Sights, in which visitors were informed that: “…in a word, Miss Linwood’s exhibition is one of the most beautiful the metropolis can boast and should unquestionably be witnessed, as it deserves to be, by every admirer of art.”

Mary Linwood, self portrait @ Tate

Mary worked in crewel wool which she dyed herself to obtain the colors she needed. Working on twilled linen backing fabric, she created her signature look of brush strokes by using stitches of irregular lengths and blending silk for dimension and shimmer. Most of her works were full-size copies of paintings by notable artists of the day, including Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.” Mary is credited with popularizing Gainsborough’s “fancy pictures” and her reproduction of his renowned The Woodman serves as the most faithful record of the original, which was destroyed in a fire in 1810 along with works by Titian, Rubens and Teniers.

“Viewing Miss Linwood’s needlework is humbling for any female who fancies herself accomplished,” said Charlotte. “If girls devoted themselves to Latin and the Classics with such energy, think of the professions women could enter.” Alverstone, Beatrice Knight

Mary Linwood has her detractors and the artistic merits of her works are a matter of debate, but as a businesswoman and intelligent marketer, she had few rivals among women of her class and era. Her last work, The Judgement of Cain, was 10 years in the making and completed when she was 75 years of age. She was buried in St Margaret’s Church, Leicester.