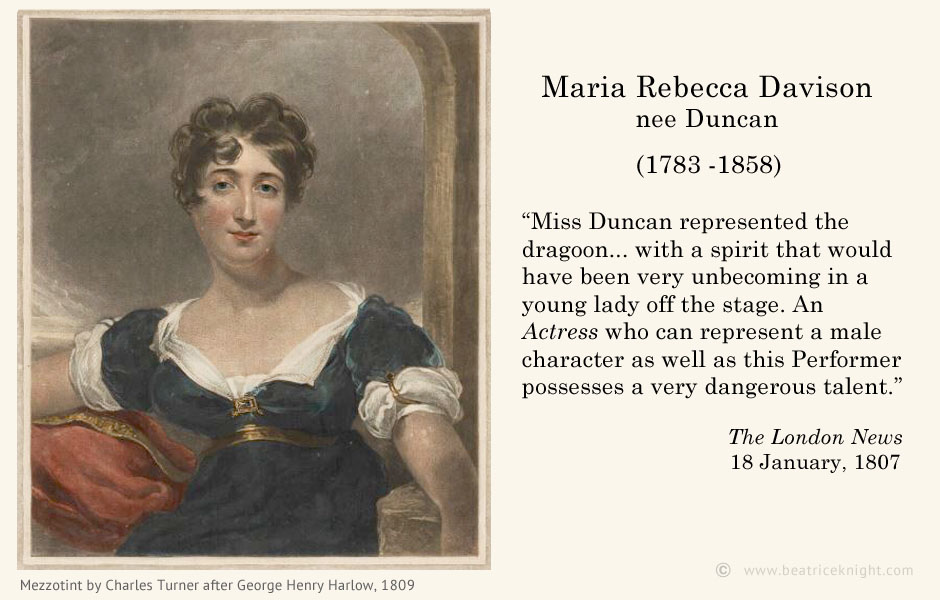

Maria Rebecca Davison “Miss Duncan”

(1780 – 1858)

A stage celebrity and style icon, who made her name as Miss Duncan, Maria Davison is largely forgotten by history, but in her day she rattled a few cages by playing male roles and making demands theater managers thought outlandish, such as requesting fire safety checks.

In 1809, The Monthly Mirror (1 November) found Miss Duncan less than handsome, observing: “...she is a very clever actress, but her face was made for Drury-lane stage–we love her best at a distance. She promises soon to be what is elegantly called, a horse god-mother.” Miss Duncan was not a big name like Mrs. Siddons, but she was already making her distinctive mark on British theater back then.

The daughter of actors who worked predominately in the north of England, Maria Rebecca Duncan spent a decade in provincial theatre, appearing in York, Doncaster, Liverpool, Dublin and Edinburgh. She received her first notices in 1797-98 as 18-year-old “Miss Duncan from Dublin” (Monthly Mirror), a member – with her parents – of the York company under Mr. Wilkinson’s management. She had been acting since childhood and numbered among her juvenile appearances a turn as the Duke of York alongside George Frederick Cooke’s Richard III in 1794.

Being tall and strong featured, she was a logical fit for male roles and created some buzz for these parts, but Miss Duncan did not intend to spend her life in the provinces. After a successful season in Wakefield she was reported (Monthly Mirror, September 1800) as resigning from Mr. Wilkinson’s company, supposedly for “tender” reasons. A month later, lamenting her “almost irreparable” loss, the same arts publication reported her “advantageous engagement with the managers of the Edinburgh theatre.” Six months later, London’s Morning Post was favorably comparing her to Drury Lane star and mistress of the Duke of Clarence, Mrs. Dorothea Jordan (1761-1816).

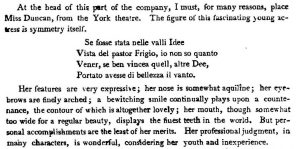

In June, 1801, the Monthly Mirror published a gushy profile (left) which, after waxing on her appearance, concluded that “without being a servile imitation” she was in the mold of Mrs. Jordan. Not only was Miss Duncan seen as destined for greatness, her fund-raising clout in benefits for widows and orphans, and other charities, showed her to be a consistent audience favorite. Her 1803 benefit performance in The Country Wife was the largest ever held in Edinburgh at the time.

In June, 1801, the Monthly Mirror published a gushy profile (left) which, after waxing on her appearance, concluded that “without being a servile imitation” she was in the mold of Mrs. Jordan. Not only was Miss Duncan seen as destined for greatness, her fund-raising clout in benefits for widows and orphans, and other charities, showed her to be a consistent audience favorite. Her 1803 benefit performance in The Country Wife was the largest ever held in Edinburgh at the time.

Portrait of Mrs. Jordan by John Hoppner.

Alas, on the heels of this tribute, Miss Duncan took a role in a production that bombed in Liverpool. There ensued some back and forth on her merits between critics, none of whose opinions appeared to dent her popularity. Miss Duncan applied herself to a series of roles including Rosalind, Beatrice, Letitia Hardy, and Hippolyta, and in March 1803, she was reported as receiving a “Most liberal offer from the managers of Covent-Garden,” but she continued performing for the northern audiences, and drew big crowds in Glasgow. Finally after a series of hits for the Edinburgh theatre, Miss Duncan accepted an offer from Mr. Wilmot Wells of the Margate Theatre in July 1804, dipping her toe to see how she would be received in one of the fashionable spa destinations favored by the ton.

It was a dark and stormy night

Miss Duncan made her debut as Letitia Hardy on an evening that seemed ordained for a performance of The Tempest. Fierce storms slammed Margate. A vessel from Dover was driven aground and a London attorney washed overboard to his death. Jittery patrons descended on the theatre early and cranky after a day trapped indoors without their usual diversions. Faced with a packed house, pounding rain overhead, and wildly careening candle-lamps, Miss Duncan rose to the occasion, bringing much-needed comic relief to an audience that ended the evening madly in love with her.

Londoners reading the Morning Chronicle the next day (16 August, 1804), saw a swooning review that likened her to the famed Miss Farren. Newspapers all but asked outright why deserving metropolitan sophisticates had been callously deprived of this luminary while Philistines in the north hugged her to themselves for the past decade. Or, as the Courier elegantly pondered: “If, under the chilling breezes of the north, this fair plant has flourished, what may not the sunshine of a London audience effect?”

Meanwhile, in Margate, Miss Duncan shone in another comedic role as Mrs. Sullen in the The Beaux’ Stratagem, and sang extremely well in the entertainment that followed each performance. So many visitors descended on Margate, eager to see her, that new arrivals were “obliged to sit up at the Inns all night for the want of beds.” Among the beau monde was Almack’s patroness the Countess of Cholmondeley, who promptly sponsored a Benefit for Miss Duncan. The Courier reported on the “great assemblage of Belles and Elegantes” in the boxes that night to enjoy Miss Duncan’s Tomboy.

Days later, Miss Duncan was fielding offers from theatres all over the realm.

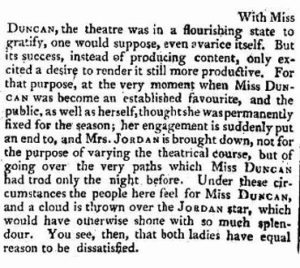

The Rivals

Inevitably a rivalry hit the headlines. Mrs. Jordan, no doubt curious about the shiny new Miss Duncan, arrived in Margate to a town jammed with more visitors than it had seen in the past eight years. There transpired a debacle. Miss Duncan, having packed houses all season, arrived to perform and found herself summarily kicked to the curb and replaced by Mrs. Jordan, who was engaged to play the same characters in the same theatre just sold out by Miss Duncan during the preceding  weeks.

weeks.

The public, having taken Miss Duncan to their bosom, witness their young “Heroine of Margate” insulted by greedy, opportunistic theatre management. Mrs. Jordan played to empty houses, and could not quit town fast enough after her final performance. She then had to revisit her humiliation for weeks as every newspaper dissected the Margate episode and invented a rivalry no one, let alone an actress in her forties pregnant with her thirteenth child, would wish for.

Miss Duncan, not surprisingly, landed on her feet. No sooner was she let go than Mr. Wroughton of Drury Lane set off for Margate and signed her up to work at a salary of 15 guineas per week (roughly equivalent to $1250 today) and a Benefit. It was big money at a time when women earned only half of a man’s wage, amounting to more in a week than most maids earned in a year.

Her final days in Margate must have held a measure of satisfaction. The theatre manager came crawling back, begging her to return for eight nights in September. She gave her final performance, a benefit, in Margate on 28 September, 1804, in She Stoops to Conquer. Two days later she set off for the ‘Great City’ and would not return to Margate for many years. She had already made a brief trip to London by then to look over her new digs, during which she made something of an impromptu appearance on 24 September as Letitia Hardy in the Belle’s Stratagem by Hannah Cowley, a role she would make her own. The appearance was a more of an introduction than a theatrical debut, allowing her to acquaint herself with the theatre and its fashionable crowd.

A couple of weeks later, she drew a packed house for her formal debut on 8 October, when she played Lady Teazle to “great and deserved applause.” (European Magazine and London Review. 1 October, 1804.)

Rapturous Reviews

Miss Duncan’s debut excited reviews that ran the spectrum from breathlessly admiring to slavering devotion of the kind associated these days with South Korean boy bands. After a few days, the London Star reported that “from the very great overflow last night and the immense, unbounded applause…” for Miss Duncan’s Lady Teazle, the theater had scheduled repeat performances of the play. At Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s insistence, Drury Lane’s management board doubled Miss Duncan’s salary. On October 18, she played Rosalind in As You Like It. The performance was attended by Mrs. Abingdon, the original Lady Teazle.

In January, 1805 she claimed the role of Juliana in The Honeymoon and for many years any other actress who played it was unfavorably compared with her. As Miss Duncan consolidated her standing as perhaps the finest newcomer to tread the boards since Mrs. Siddons, whom she was acting alongside in 1806, the winds of war were blowing in Britain. Napoleon had threatened to invade. The British Navy was massing in key locations. Miss Duncan’s honeymoon had lasted two years when one of her most loyal admirers declared her “my former favorite actress” (Monthly Mirror, March 1806). That same month, Bell’s Weekly Messenger essentially accused her of believing her own publicity, writing: “Her worst enemy now is a flatterer; the best thing her critics can do is to put her out of conceit with herself; so noble and promising a performer should not be lost for the want of a little wholesale discipline.”

Miss Duncan’s benefit for 1806 was held on 7 May. Tickets could be purchased direct from her at 13 Great Russell St., Covent Garden, presumably her home, a short walk from the theatre and next door to the Hummums coffee house and hotel. She received no reviews of any special distinction, and seemed to have settled in as part of the furniture at Drury Lane. At times she taxed the public affection for her, most notably in January 1808 when she was booked to perform at the Theatre Royal in Windsor and did not show up. The house was full and boxes sold. Manager Mr. Mudie, in frustration, read aloud some correspondence exchanged with her in December. Her letters show her as living at 71 Charlotte St., and trying to juggle the two-evening stint in Windsor with her engagements at Drury Lane. She had demanded ten guineas in advance and despite Mudie’s assurances and offers of fully paid transport, she did not make the trip and was replaced by another actress.

The episode did her reputation no favors with management, but she was still young and glamorous, and her income enabled her to dress fashionably. London modistes, those not averse to linking their names to an actress, encouraged her to wear their designs and in January 1807, the Evening Post reprinted a Bell’s fashion column describing her wearing a pink Incognita hat (left). Given her youth and prominence as an actress, it’s likely that her fashion choices inspired other young women, making her an “influencer” of her time.

The episode did her reputation no favors with management, but she was still young and glamorous, and her income enabled her to dress fashionably. London modistes, those not averse to linking their names to an actress, encouraged her to wear their designs and in January 1807, the Evening Post reprinted a Bell’s fashion column describing her wearing a pink Incognita hat (left). Given her youth and prominence as an actress, it’s likely that her fashion choices inspired other young women, making her an “influencer” of her time.

Marriage

Miss Duncan married James Davison on 31 October 1812. Marriage did not pause her career. She appeared as Rosalind on 3 November, and continued working with Drury Lane until 1818. Her husband caused a few headaches, most notably in January 1815, when he assaulted an audience member whom he thought was unsettling her (she went by Mrs. Davison after the marriage). She was then pregnant, and Davison challenged the man to a duel. A few months later, he ended up in court over the assault, and was found guilty, with the court pronouncing it:

“a great offense against public opinion to restrict or control the feelings of a theatrical auditory, and that it was not to be endured that the relatives of actors or of actresses should not presume to interfere with them upon any occasion of dramatic entertainment; such conduct not only infringed upon decorum and upon the King’s peace, but upon the just discrimination and taste of the public.”

Davison, who went by Captain Davison – but did not seem to have a commission in any regiment – had to pay a fine. Barely a year later he was back in court, this time for insolvency. The court noted that he had not included in his schedule the salary and clothes of his wife for purposes of debt repayment, property which, as her husband, he owned. Davison argued that most of the debts had been incurred before he married. It’s not clear how the debts were settled. Mrs. Davison may have applied the proceeds of her benefit evenings.

She remained married to James Davison and the couple died just months apart in 1858, leaving no children.

Read More

The Thespian dictionary; or, Dramatic biography of the eighteenth century; containing sketches of the lives, productions, &c., of all the principal managers… London. Printed by J. Cundee for T. Hurst; etc., etc. 1802.

Joseph Knight and Jean Gilliland. Davison [née Duncan], Maria Rebecca 1783-1858 actress. In Gilliland, J (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press, 2004.

Tomalin, Claire. Mrs. Jordan’s Profession. (1st American ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1995