We have the Cholera Pandemic of 1826-1837 to thank for the development of the intravenous saline drip, based on the work of Dr. Thomas Latta of Leith, Edinburgh. Over 250,000 people died around the world before the pandemic burned itself out.

The Cholera Pandemic

The Causes of Disease Were a Mystery

Before modern medicine, the entire Western world believed every disease or illness, physiological or mental, was caused by an imbalance or disturbance within the body. Known as ‘humors’ these disturbances were thought to be brought about by a miasma: foul air breathed in, which contained tiny, invisible insects; or possibly an evil spirit or disruption in the earth’s magnetic field. Physicians aimed to eliminate the problematic humors through bodily orifices, most often by bleeding or purging their patient and administering remedies. Very often the “cure” was as bad as the disease and killed the luckless patient.

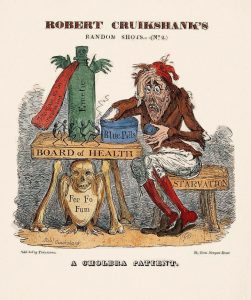

The concept of germs invading the body through contaminated water or fleas transmitting plague was proposed by a handful of early researchers who attempted to draw evidence-based scientific conclusions. The authorities were reluctant to give credence to theories that would undermine the prevailing narrative, not least because there was money involved. British doctors and hospitals were financially incentivized to admit dying patients and fail to cure them. At a hefty £10 a head per patient/corpse, cholera was a profitable pandemic. Ending it by discovering the root cause was not good for business, so they dragged their feet and clung to conventional wisdom.

Public opinion of health authorities in both the UK and the US cratered during the cholera pandemic, if the satire of the day is any indication. However, to be fair to the many doctors who tried desperately to save patients in the worst imaginable conditions, the pandemic spurred advances that culminated in the work of Pasteur and Koch in the 1850s. Among the medical workers taken during the pandemic was Dr. Thomas Latta of Edinburgh, who had saved many of his patients by using a saline drip to prevent dehydration.

Public opinion of health authorities in both the UK and the US cratered during the cholera pandemic, if the satire of the day is any indication. However, to be fair to the many doctors who tried desperately to save patients in the worst imaginable conditions, the pandemic spurred advances that culminated in the work of Pasteur and Koch in the 1850s. Among the medical workers taken during the pandemic was Dr. Thomas Latta of Edinburgh, who had saved many of his patients by using a saline drip to prevent dehydration.

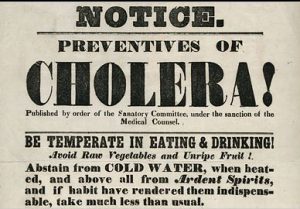

Eventually English and European medical science would conclude that disease could be caused by germs, and lives could be saved through clean water and social distancing. American doctors resisted the breakthroughs for as long as they could. The poor, whose squalid living conditions facilitated the spread of contagious diseases, were blamed for their own illnesses. Moral degeneracy and alcohol gave politicians the chance to point fingers while doing nothing about open sewers and lack of clean water. Public works cost money.

The Irish did it

During the Second Cholera Pandemic, the American authorities blamed Irish immigrants for the spread of cholera, and it was certainly true that travel spread the disease. The first (1817-1824) of the two Regency cholera pandemics had spread an unprecedented distance from its Calcutta origins, sweeping through Southeast Asia, China, the Middle East and eventually the Mediterranean. British soldiers became infected and died, which raised some eyebrows back home.

The second pandemic spread much farther, crossing Russia, where it claimed 100,000 lives, and entering Poland in 1831, carried by Russian soldiers sent to put down a Polish rebellion. As reports reached the British, they issued quarantine orders for all shipping between Russian and British ports. It seemed inevitable that the disease would spread through England, so the Board of Health issued orders for a kind of national spring cleaning. The public was ordered to burn filthy and decayed items, boil clothing in lye, toss lime in drains and privies, and air their houses thoroughly. These advance measures were thought to address the “miasma” that caused disease.

It was already too late. Cholera had entered via passengers on a ship from the Baltic.

Quarantine was the first and only recourse, and it didn’t work

Europe had faced bubonic plague and other epidemics over the centuries and relied primarily on quarantine to slow contagion. As the cholera pandemic spread during the 1830s, economies were shuttered, trade slowed and people in unaffected enclaves wrote a lot of letters to fill in time, providing first hand accounts of goings-on around them.

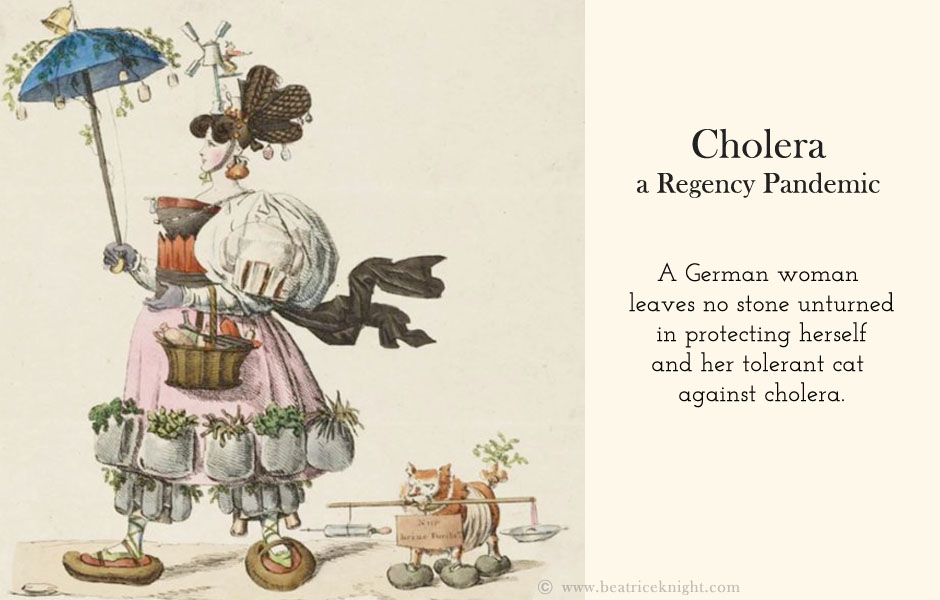

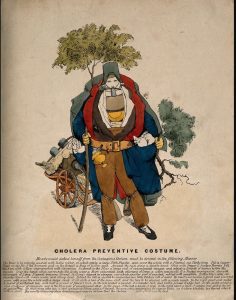

The quarantine system had not stopped the black death or smallpox, and it did not stop cholera. Unimpressed with the approach of health authorities, the public adopted countermeasures. English and Europeans came up with outfits people could wear, designed to repel the miasma. Fires were lit because diseases have an aversion to smoke, obviously. And some communities introduced an early form of social distancing.

The quarantine system had not stopped the black death or smallpox, and it did not stop cholera. Unimpressed with the approach of health authorities, the public adopted countermeasures. English and Europeans came up with outfits people could wear, designed to repel the miasma. Fires were lit because diseases have an aversion to smoke, obviously. And some communities introduced an early form of social distancing.

New York City Board of Health Notice 1832

The second cholera pandemic was significant because of its vast global spread and huge death toll, but also because it shone a spotlight on the dismal failure of health boards to prevent disease spread and to treat the sick. Understanding that there would be no improvement until doctors understood the cause, transmission, and treatment of cholera, sparked a race to learn from the lessons of the pandemic and understand how to prevent the next disaster.