During the Regency era, inventors and scientists in several countries were hard at work trying to devise a means of communicating at a distance. Their efforts led to early versions of both telegraphy and the facsimile machine

The Telegraph

Semaphore telegraph started a long time ago

When Greek army commanders in 400 BC wanted to transmit a message across a distance without a horse and rider they used a signaling system devised by tactician, Aeneas Tacitus, which involved torches and water-filled pots synchronized in a convoluted manner between signal stations. According to the Greek historian Polybius, this ancient hydraulic semaphore telegraph was used during the First Punic War to transmit messages between Sicily and Carthage.

While elaborate hydraulic systems were in the too-hard box for most early peoples, various combinations of fires, smoke, drums, and bell ringing were used all over the world to send signals whose meaning was agreed in advance, such as “Run! Enemy canoes,” or “Break out the mead. The queen just had a son.” Long before the Greeks, the Chinese used beacon towers along the Great Wall, sending signals by fire at night or smoke (preferably fueled by wolf dung) during the day. In an early example of misuse of telegraphy, King You of the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century BC – 771 BC) brought about his own downfall by having the beacon towers lit to amuse his favorite concubine, Bao Si, for whom he had deposed the queen and crown prince. After scrambling one time too many for her amusement, the soldiers did not bother to come when the deposed queen’s father, the Marquess of Shen joined forces with the Quanrong in an attack on the Zhōu capital, Haojing. King You was killed, the lovely Bao Si captured. The Western Zhou Dynasty was swept away, and supplanted by the Eastern Zhou – a cautionary tale for another day.

Science nerds spent 200 years developing a telegraph for coded message transmission

Returning to modern telegraphy, in 1616, in Cologne, Germany, alchemist and diving bell inventor Franz Kessler came up with possibly the first ever telegraph system based on alphabetic code. He placed a lamp in a barrel with a moving shutter, and relayed signals to be observed from a distance by another new invention, the telescope. His system intrigued science nerds in England and Italy, who focused on advancing the optical element. In 1684, an English mathematician and architect, Robert Hooke, designed an optical telegraph system based on semaphore (indicator pointers). He presented his idea at the Royal Society. It went nowhere until eighty years later, when Sir Richard Lovell Edgeworth (father of Regency celeb novelist, Maria Edgeworth) picked up the concept and designed an optical telegraph line for Ireland, which he installed as an experiment.

Sir Richard was all about road improvement and conceived of and patented the rolling caterpillar track subsequently used for tanks and heavy machinery. His concept was a century ahead of its time, and although he built a hundred working models, the machine he envisioned could not be successfully produced within the constraints of his era. His patent would expire and vanish, doubtless filed in the “crackpot” section of some archive.

Claude Chappe (1763-1805)

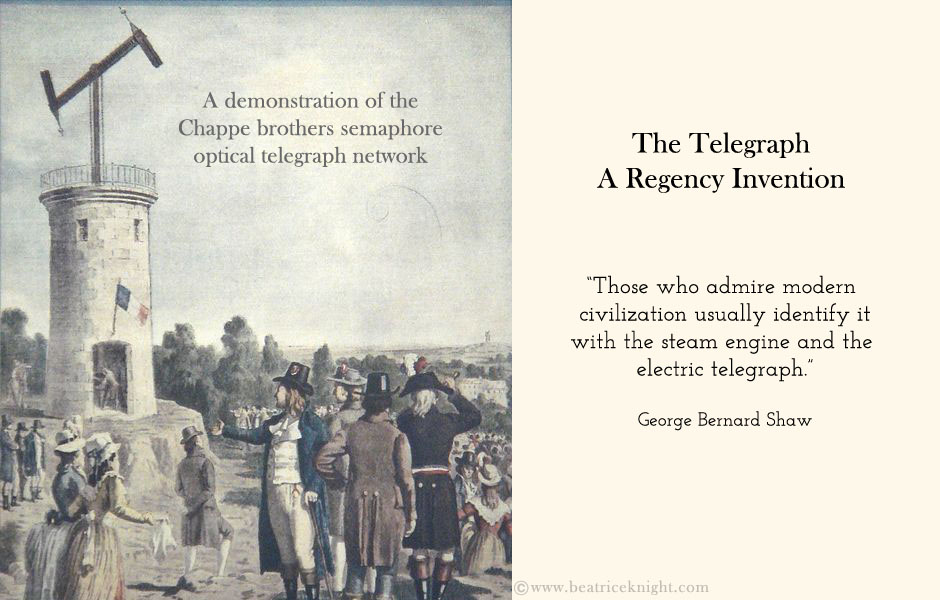

Meanwhile, work on the optical telegraph accelerated in France, where Claude Chappe and his four brothers set up the first successful optical telegraph network. They seemed eager to help the newly installed Revolutionary government receive intelligence and transmit orders. During their first public demonstration, they sent a test message from Brûlon to Parcé, about 10 miles away, which read: “Si vous réussissez vous serez bientôt couvert de gloire [If you succeed, you will soon bask in glory].” After some lobbying in the shifting political scene in Paris, where brother Ignace Chappe had initially served on the Legislative Assembly, Chappe’s project was finally approved on August 4th, 1793 and he was appointed “Telegraph Engineer” supervising the construction of a line of stations from Paris to Lille. His network became operational in 1793 and carried dispatches for the war between France and Austria. A similar system was set up in Sweden by Abraham Edelcrantz.

Chappe’s telegraph played a significant role in the Napoleonic Wars, yet as various Johnny-Come-Lately inventors claimed to have created better telegraphs or even accused Chappe of stealing their ideas, he sank into depression and, in 1805, took his own life directly outside the Telegraph Administration building in Paris.

A complete Chappe telegraph station still exists in Lyon. The tower has all the original equipment, logbook and technical instruction manual, and even the operator’s office and sleeping quarters. Another tower, built in 1809 in the village of Annoux, was restored in the 1990s. Located on the semaphore line between Lyon and Paris, it seems likely that this was among the towers that transmitted the alert of Napoleon’s return from Elba in 1815.

The Electrical Telegraph during the Regency

1809. Electric telegraph invented by Samuel Thomas von Sömmering.

In 1816, English inventor Francis Ronalds built the first working telegraph in a 175 yards-long subterranean trench at his home in tandem with an eight-mile length of overhead telegraph. The lines were connected at both ends to revolving dials marked with the letters of the alphabet and, using static electricity, he transmitted impulses along the wire messages. Seeing it’s obvious applications for the military, he offered his invention to the British Admiralty in July, 1816. They thought it “wholly unnecessary”…after all, they’d won Trafalgar without such new-fangled whodackies.

Ronald published his ideas on rapid global communication in Descriptions of an Electrical Telegraph and of some other Electrical Apparatus, the first published work on electric telegraphy, and elements of his Ronalds’ design would be used 20 years later when the telegraph was commercialized.

During the two decades after his invention, a number of scientists evolved the concept, most notably Schilling (1832) and Gauss and Weber, who built an electric telegraph that connected two buildings a kilometer apart.

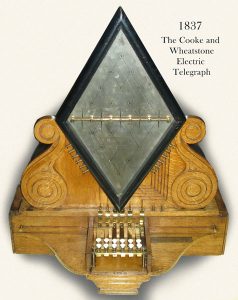

Cooke and Wheatstone Electric Telegraph. 1837

In the race to commercialize the telegraph, English inventor Sir William Fothergill Cooke co-developed the Cooke-Wheatstone telegraph system with Charles Wheatstone, which used electro-magnets in its receiver that moved needles on a board to indicate letters of the alphabet. They patented the Cooke and Wheatstone system in May 1837 and in 1845, Sir William teamed up with British financier, John Ricardo, to found the world’s first public telegraph company. The Electric Telegraph Company, as it was known, secured railway communications contracts for Britain and most of its empire. Various systems of theirs remained in use until the 1930s.

Morse and Vail

Concurrently with Cooke and Wheatstone, but independently, American painter and inventor, Samuel Morse developed a single-wire electrical telegraph system with mechanical engineer Alfred Vail based on European telegraphs. He also co-developed Morse code, an encoding system designed for sending messages by making indentations on a paper tape when electric pulses were received. The system was an early forerunner of modern International Morse code. Morse code operators were taught to translate the indentations into text messages. It was adopted internationally and later used extensively in radio communications.

Morse’s method was less expensive than Cooke and Wheatstones and commercially outpaced them in the United States and Europe by the end of the Regency era.

Read More

Chappe, Ignace. (1824) Histoire de la télégraphie.

Whitehead, David. (1990). Aineias the Tactician: How to Survive Under Siege. Bristol Classical Press.