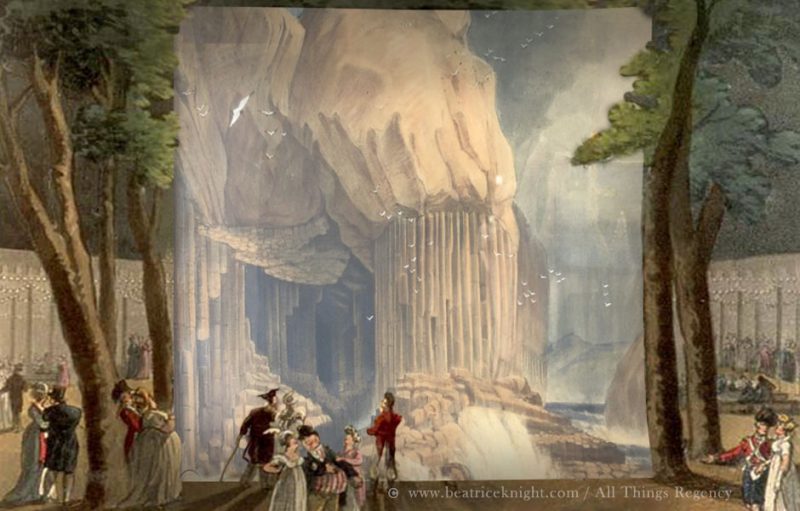

If you turned a corner at Vauxhall Gardens two centuries ago, you were likely to stumble across the Regency version of a hologram: a huge backlit transparency depicting a natural wonder like Fingal’s cave (above), a battle victory, or a romantic scene from some far-off place. At a time when electric lighting was yet to be invented, the public was enthralled by these illuminations.

Regency Illuminations

In addition to huge public displays, transparencies were hot hobby trend for genteel ladies, who painted images on paper or lightweight fabrics like silk and muslin, and then added varnish to create a see-through effect. They made their transparencies into candle shades, fire screens, and window art.

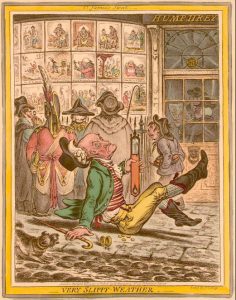

The J. Gilroy engraving (left) shows festive transparencies on display in the window of print-seller Humphrey, 27 St James St. During public celebrations and holidays, illuminations drew crowds to shop and tavern windows much as Macy’s iconic Christmas window displays do today.

The J. Gilroy engraving (left) shows festive transparencies on display in the window of print-seller Humphrey, 27 St James St. During public celebrations and holidays, illuminations drew crowds to shop and tavern windows much as Macy’s iconic Christmas window displays do today.

By far the most stupendous transparencies were found at pleasure gardens like Vauxhall, where the Submarine Cave was a massive eighty feet high at the arch. Painted in 1822 by father-and-son staff artists, the Thorns, this attraction burst into life at 10 pm each night, enhanced by waterworks and illuminated by countless concealed lamps. Long before the Submarine Cave, the Cascade had enraptured the Vauxhall crowd since 1752. Revamped through the years, the experience was described in The Microcosm of London (1808-10):

“…usually about ten o’clock, a bell is rung by way of signal for the exhibition of a beautifully illuminated scene, called the cascade. A dark curtain is then drawn up, which discloses a very natural view of a bridge, a water-mill, and a cascade; a noise similar to the roaring of water is also well imitated; while coaches, waggons, soldiers and other figures, are exhibited crossing the bridge with the greatest regularity. This agreeable piece of scenery continues about ten minutes…”

Although gas lighting was being installed through the streets of London from 1807 onward and shops were beginning to embrace the new innovation by 1810, homes would not make the leap until the 1850s. Artificial lighting was both a marvel and a status symbol in Regency England; nothing dented household prestige like a drawing room lit only by a few smoky, smelly tallow candles. Affluent households burned clean, bright beeswax or spermaceti (whale oil) candles, and positioned gilt mirrors around the walls to boost lighting.

But with beeswax candles taxed at 8 times the amount paid on tallow, even prosperous families avoided lighting countless separate rooms. Family and guests would get together of an evening in the most well-lit space in the house: the drawing room, a feminine space where women’s accomplishments were showcased: piano and harp, singing, and – during the craze – transparencies. In Mansfield Park, Jane Austen mentions the Bertram sisters’ had fashioned: “…three transparencies, made in a rage for transparencies, for the three lower panes of one window, where Tintern Abbey held its station between a cave in Italy and a moonlit lake in Cumberland…”

Perspective print transparency with cutouts: Isfahan street scene 1760. Unknown artist.

Perhaps the Bertrams learned their handicraft from Rudolph Ackermann’s Instructions for Painting Transparencies (1799). Ackermann published 109 transparent etchings for domestic hobbyists between 1796-1802. Another engraver, Edward Orme promoted transparency-making via his bestselling manual: An Essay on Transparent Prints and on Transparencies in General (1807). Orme was a favorite for his gloomy Gothic castle prints and simple transparency technique: just paint the back of an etching or engraving with colors matched to the outlines of the illustration, and then add varnish for translucency. Viola!

Tiny cutouts and surface scraping could add extra bling, a principle also used in some large professional transparencies and also small illumination prints like the engraving (right) of a street scene in the city of Isfahan, Persia (now Iran). The punch holes in this image are covered by thin, colored paper and designed to let light through for perspective and drama.

War and Peace and Splendid Illuminations

When Britain’s military hero, the Duke of Wellington (a marquis at the time), defeated Napoleon in Spain at the Battle of Vittoria (June 21, 1813), it was a big deal. Coming a year after Wellington’s victory at Salamanca, Vittoria marked the beginning of the end of the Peninsula War.

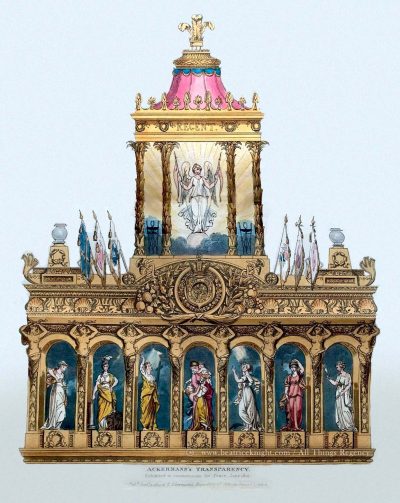

As news of the victory reached England, cannon boomed, fireworks erupted and all of London lit up. Homes, shops, and taverns competed to dazzle passers-by. Print shops instantly sold out of every patriotic transparency, including Ackermann’s. Experts in engravings for illumination, they plastered their building with new-fangled gas lights and went all out with a huge transparency hailed as “splendid in the extreme” depicting “our island Britannia” in a marine carriage drawn by dolphins and awash in naval imagery, receiving from Time an account of Wellington’s victory.

The Morning Post of July 6 announced: “The splendour of the illuminations excelled any similar display we have ever witnessed.” and provided a guide listing the most spectacular displays. Among these was “a noble transparency” featuring the Marquis of Wellington: “…the Guardian Angel of Britain was in the act of crowning him with laurel, and Fame with her trumpet was proclaiming the hero’s immortal achievements…. In the upper part of the transparency were the words “Salamanca” and at the base “Vittoria”…”

Robert Laurie (1755-1836) A View of the Temple of Concord Erected in the Green Park, to Celebrate the Glorious Peace of 1814, Exhibiting the Fireworks on the 1st of August, September 9, 1814. Etching and engraving, hand colored.

The Spanish ambassador decorated his residence with some 1300 variegated lamps and “a transparency of immense size” draped with flags and bearing a victory inscription from his nation.

Almost a year later the Treaty of Paris was signed and thousands turned out for the peace celebrations. In the Green Park, Lieutenant Colonel Sir William Congreve organized the construction of the Temple of Concord, a revolving structure which featured huge transparencies lit from behind with rows of oil lamps. He commissioned leading artists like Thomas Stothard to paint the transparencies around the theme ‘The Triumph of England under the Regency’.

Congreve (1772–1828) had served in the Peninsula Wars and led the the so-called ‘rocket brigade’ at the battle of Leipzig (1813). He also created fireworks for the occasion, including a rocket that exploded into “stars” like the fireworks of today.

Ackermann’s Transparency. Peace Treaty of Paris. 1814.

Print sellers at the parks sold images of the temple, including one by Edward Orme, which must have been eagerly snapped up by ladies who had witnessed the real thing and wanted to create a commemorative transparency for their homes. For those who missed out, Ackermann’s also published a transparency (left) for sale in their printshop.

Meanwhile, in Bath

London was not the only place where huge transparencies drew crowds. When visiting Bath in 1799, Jane Austen was struck by the illuminations and fireworks at Sydney Gardens, sometimes described as the “Vauxhall of the West.” The Austen family decided to move to Bath in 1801 and began searching for a home to rent. In a letter to her sister Cassandra (January 21-22, 1801), Austen wrote : “…it would be very pleasant to be near Sydney Gardens!—we might go into the Labyrinth every day.” She and her family lived at 4 Sydney Place, near the Gardens from 1801-1806.

The Labyrinth offered a veritable vortex of transparencies, some so startling that ladies prone to fainting were warned ahead of time. The Gardens upped their game with periodic Grand Galas such as one held in September, 1812. For two shillings admission, visitors were dazzled by the Pandean band of Vauxhall fame and a version of Vauxhall’s Cascade, along with fireworks, and illuminations “in a style peculiarly brilliant and novel, and decorated with Chinese Lanthorns, the Transparency of the Town and Harbour of Cadiz; and various Devices, emblematical of the late Glorious Victories in Spain by the Marquis of Wellington.” In August, 1813 transparencies of the Temple of the Sun and Wellington on Horseback were unveiled, and a year later multiple transparencies recreated the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

Transparencies For Profit

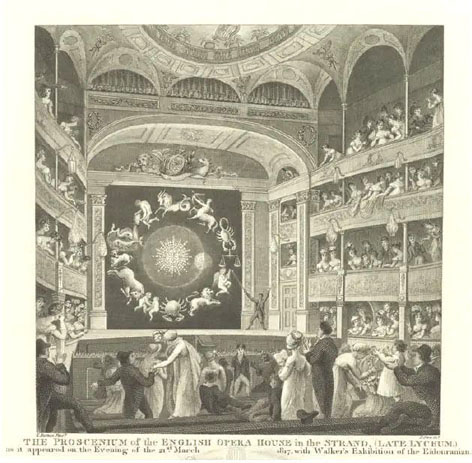

Walker’s Eidouranian displayed 21 March 1817. Image: Robert Wilkinson, Londina Illustrata (London, 1819–25), vol. 2, plate 203. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Adam Walker harnessed the visual power of transparencies to turn his lectures on astronomy into appealing theatrical events with his “Eidouranion, ” a mechanical device that seemed to function like an orrery and reportedly showed the motion of planets and moons by means of globes against a transparency of the cosmos.

This “elaborate machine” was described in the Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser (Jan. 25, 1782) as:

“…20 feet square, [it] stands vertical before the spectators; and its globes are so large, that they are distinctly seen in the most distant part of a theatre. Every planet and satellite seems suspended in space, without any support, and perform their annual and diurnal revolutions without any apparent cause. It is certainly the nearest approach to the magnificent simplicity of nature, and to its just proportions as to magnitude and motion of any Orrery yet made; and besides its being the most brilliant and beautiful spectacle, it conveys to the mind the most sublime instructions.” Walker and his family made a fortune in ticket sales between 1780 and 1830, captivating crowds through Britain and the Continent.

Very few transparencies survived the test of time; the varnish degraded and crumbled, causing the whole image to disintegrate. For that reason well-preserved Georgian and Regency transparencies fetch quite a sum at antique auctions.