Regency Matchmakers: In 1810 at the Court of Chancery a marriage broker took legal action to recover fees from a client who refused to pay when he failed to snare his ideal bride.

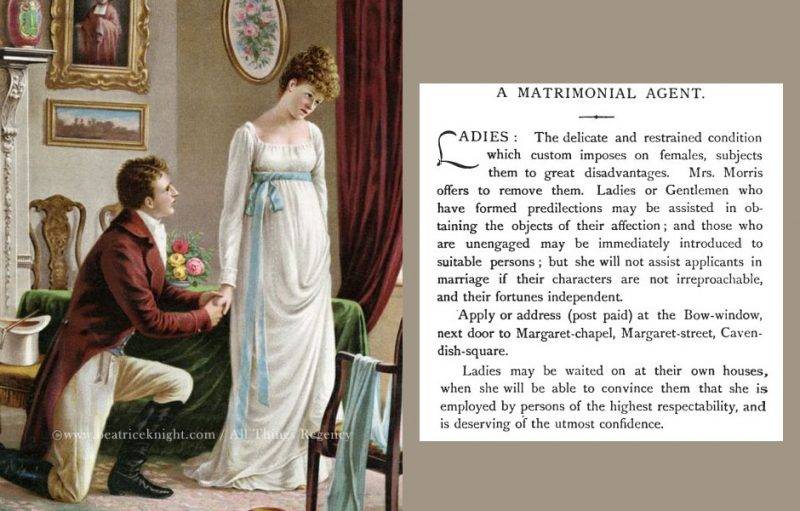

In his quest to find a wife of rank and wealth (he stipulated she should bring £1500 a year to their union), General Burr had paid a retainer of £20 to Mrs. Morris of the “Marriage Institution,” Margaret St. Cavendish Square. Sources vary on the fee he had agreed to pay on the day of his marriage: either £1000 or £3000 (approx US $73,000 or $219,000 in today’s buying power). Keen to oblige, Mrs. Morris connected the general to a high-flying associate, Mr. King, who agreed to host “ostentatious entertainments” where Burr could meet suitable ladies.

Balls, routs and parties were duly held and he had his shot with potential brides. In court, Mr. King claimed Burr made “honorable love to many of them, with the intention of being wedded…” No marriage ensued, and Burr refused to reimburse the £400 incurred by King, who took action in the Court of King’s Bench for breach of promise. Burr denied he had ever agreed to reimburse the costs of fancy parties and the criminal case failed. King then attempted a civil claim to recover his money. Burr’s counsel argued that since marriage brokage contracts were illegal and improper, money outlaid under them could not be recovered. The case was dismissed with the presiding judge, Lord Eldon declaring Mr. King “shall have no assistance from me” in a profit-driven matchmaking enterprise.

Regency Matchmakers information

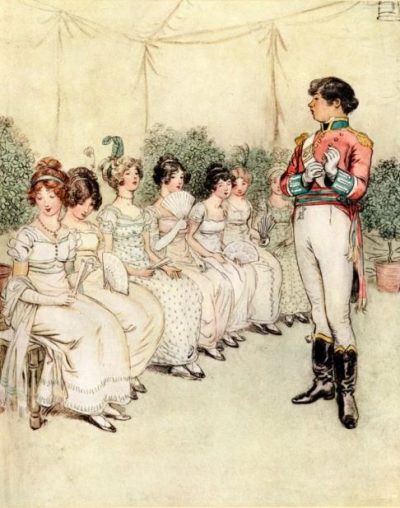

Hugh Thomson, illustration for Quality Street by J.M. Barrie

Matchmaking, as a paid profession, had been banned a century earlier. With so much power and wealth at stake in unions between elite families, it seemed reckless to outsource suitable introductions to members of the humbler classes. Matchmaking was, after all, the avid preoccupation and collective endeavor of upper class society. According to statistical research by David Thomas, daughters of the haut ton married overwhelmingly within their own class. This remained the norm until World War I turned British society upside down.

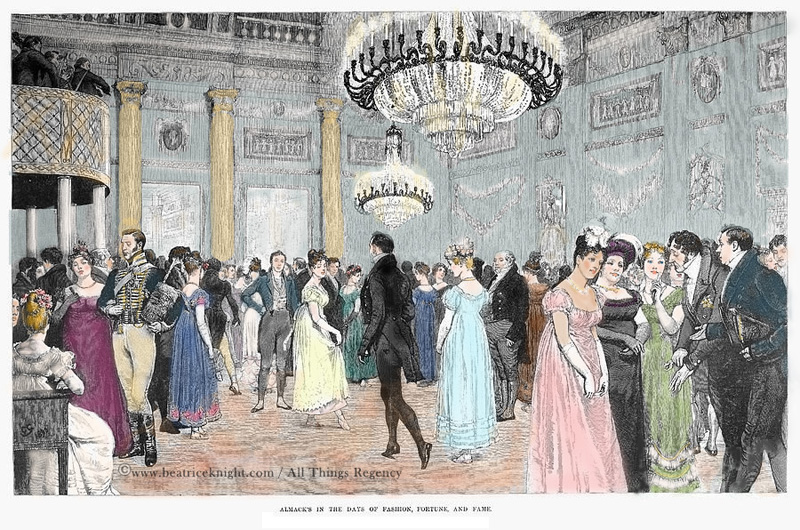

During the Regency era, the Season was essentially a marriage mart for the elite. Young ladies were wheeled out at social events where they could impress suitable partners, with undesirables weeded out by the married women who controlled the guest lists. The most notorious of high society’s gatekeepers were the lady patronesses of Almack’s Assembly Rooms, whose arbitrary tyranny could make or break any young woman’s prospects.

Marriage brokers still had a role to play, especially for an emerging middle class new to wealth and faced with the complex negotiations around property, entails, jointures, marriage portions, and pin money. In For Better or for Worse, John Gillis notes: “Matchmakers sometimes had to enter into complicated transactions with the relatives of the couple in order to get their approval.”

Alliance or Affection?

Despite the general disdain for her occupation and the precarious legal status of agreements with clients, Mrs. Morris advertised her services in London in 1807 and was in business for several years before the court case drove away her clientele. Matrimonial agents also operated in large cities like Manchester. In contrast, while English society already waxed on the ideal of love matches as far back as the 1760s, the Europeans continued to view marriage primarily as an alliance. The French thought “marriage by fascination” a silly idea well into the 1850s – love could be found outside of wedlock.

Marriage brokers like Claude Villaume did a brisk trade. When he opened his Agence Générale et Centrale pour Pais et l’Empire on Rue Neuve-Saint-Eustache in Paris in 1812, he reported being swamped with clients and transacting 206 marriages in his first two months of business. By 1818 he bragged of successful matches arranged as far afield as Europe to North Africa and America.

Charles E. Brock, illustration for Mansfield Park by Jane Austen

The true matchmakers of Regency England were female relatives and close family friends who took the role of emissaries in an approved courtship, and attempted to thwart potential disasters. Not surprisingly, with marriage being the central drama of women’s lives, matchmaking was a major theme in 19th century novels. While Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse (Emma, 1816) jumps to mind for today’s reader, Austen’s contemporaries would have been more familiar with Maria Edgeworth’s character Selina Stanhope, the match-making aunt from Belinda (1801) whose calculating priorities contrast with her niece Belinda’s principles, as she struggles with social rules and expectations.

The English upper and middle class evolved a marriage style that combined alliance and affection, passion and practicality. During the Victorian era the balance of romance and realism became the foundation for English family life among the prosperous and aspiring classes.

Read More

Austen, Jane. Emma. (1816). The Project Gutenburg Ebook, 2010.

The Gentleman’s Magazine. January 1813. London.

Edgeworth, Maria. Belinda. (1801). Oxford and New York: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008.

The Edinburgh Annual Register Volume 3, Part 2 (1812).

Gillis, John. For Better, For Worse. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Journal des Dames et des Modes v. 6 (Paris, 1812), p. 349.

Kloester, Jennifer. Georgette Heyer’s Regency World. London: William Heinemann, 2005.

Thomas, David. The Social Origins of Marriage Partners of the British Peerage in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Population Studies 26 (1972): 99-111.

The Times Law Reports Volume XXI. London: George Edward Wright, 1904-1905

Tuite, Clara. Romantic Austen: Sexual Politics and the Literary Canon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.